New Dimensions For Old Manuscripts

Apparently, you can teach an old poem new tricks.

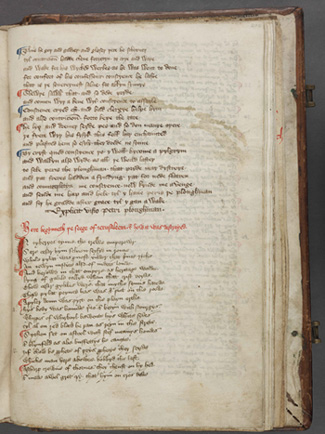

When an unknown 14th Century poet was writing The Siege of Jerusalem, there is no way he or she could imagine the computer age. They had no way of knowing that seven centuries later the poem would lead to the development of a digital labor of love, fostering a new generation of research into the literature of the Middle Ages.

Why would someone want to create an electronic archive for a medieval poem that most people have never heard of? Because it represents a significant advance for period scholars. Just ask Dr. Tim Stinson, since the Siege of Jerusalem Electronic Archive is his baby. “Digital media allow us to convey the fluidity and variance of medieval texts in a way that printed material does not,” Stinson says. The archive will let scholars around the world view all of the various manuscripts of The Siege of Jerusalem. No small feat, since the manuscripts themselves are scattered around the world.

The Siege of Jerusalem is an English poem dating to the 1300s that tells the narrative of the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70 – an event that led to the dispersal of the Jews. Medieval artists, writers and thinkers were very preoccupied with this event, leading to a number of works revolving around the siege. However, the accepted narrative in the Middle Ages was that the Romans were “Christian knights,” and that Rome and Christianity replaced Jerusalem and Judaism. Of course, we now know this is horribly historically inaccurate (the Christians were actually besieged inside Jerusalem with the Jews), but I digress.

What drew Stinson to the poem, aside from its artistic excellence, is the fact that the siege had a great deal of socio-political importance in the Middle Ages – and that there are eight different manuscript versions (plus one additional fragment) in existence, which is rare for this type of poetry. “Examining these different manuscripts allows us to see the context in which they were read and circulated,” Stinson says. “For example, sometimes the poem was included in a collection of devotional works, and sometimes it was in a collection of martial and historical texts.”

But comparing the manuscripts is not easy, since the extant manuscripts are scattered across seven different locations on two continents. That’s about to change.

Stinson, an English professor and digital humanities scholar at NC State University, explains that the electronic archive will include digital images of all the manuscripts, as well as transcriptions of the manuscripts. Stinson, who is developing the archive with funding from a digital humanities fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities, is also encoding the electronic transcriptions. This coding will allow researchers to search and sort the entire body of manuscripts in order to analyze things such as dialect, spelling, poetic meter, and the physical features of the manuscripts themselves.

“Studying the manuscript texts allows us to consider the differences between each manuscript,” Stinson says. “Each scribe made changes to the text as they copied it. This can tell us a lot about how literature was received, transmitted – and, ultimately, evolved – during the Middle Ages.

The archive, which should be complete in 2011, will also include additional historical texts that were likely used as source materials for The Siege of Jerusalem. The data will be curated and disseminated by NC State’s library system.

- Categories: