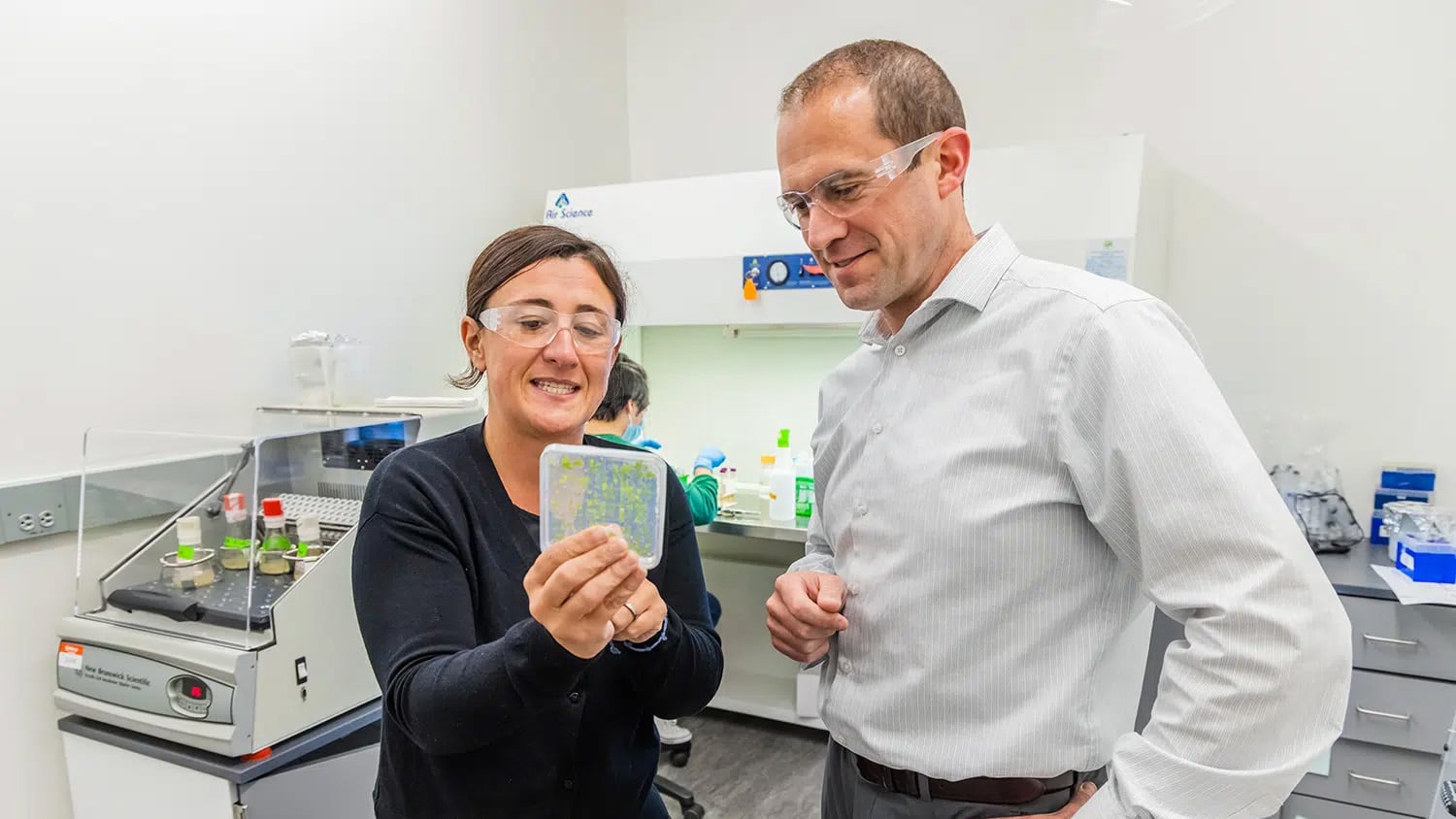

Dr. John Cavanagh and Dr. Christian Melander

It started out as a research project focused on getting rid of harmful bacterial accumulations called biofilms. Now it has the potential to make conventional antibiotics work against stubborn, drug-resistant bacteria.

This unexpected development might have come as a surprise to the NC State researchers involved in the project, Dr. Christian Melander, associate professor of chemistry, and Dr. John Cavanagh, William Neal Reynolds Distinguished Professor of Molecular and Structural Biochemistry.

What’s not surprising, however, is the researchers’ willingness to try seemingly unusual or unconventional methods to solve common problems. After all, getting rid of biofilms meant figuring out something odd to people who aren’t chemists: how to safely and efficiently mimic a sea sponge.

Bacteria have a number of ways of protecting themselves from antibiotics, including casing themselves in a protective barrier known as a biofilm. Biofilms comprise about 80 percent of the world’s microbial environment and are, according to statistics from the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control, responsible for up to 80 percent of all bacterial infections.

In addition to medical concerns – certain biofilms in the lung kill cystic fibrosis patients, for example – biofilms also have enormous impacts in agriculture and industry. Biofilms destroy crops, foul ship’s hulls and coat medical devices. Biofilms also coat – don’t be alarmed – your teeth. As anyone who has had plaque scraped from their teeth knows, getting rid of biofilms once they adhere to a surface is really difficult.

To create chemical compounds that can scrub away biofilms, Melander and Cavanagh looked to a particular sea sponge, Agelas conifera, that lives in the Caribbean Sea.

“Somehow, this sponge that can’t run away and that has no immune system stays remarkably clean while everything around it is covered in biofilms, so the sponge has some molecular way of keeping them at bay,” Cavanagh said. “We’ve never seen a sea sponge up close, but we understand the chemical processes going on. So Christian devised chemical compounds to mimic the sponge compound, ageliferin, that keeps the sponge free of biofilms. Our compounds are not toxic to mammals like ageliferin is, though, and we can make the compounds in enormous quantities.”

The NC State chemical compounds don’t kill biofilms outright, but cause them to revert to their single-celled form. Common antibiotics are then able to do their job of eliminating the single-celled bacteria.

Melander and Cavanagh started a company called Agile Sciences to continue working on solutions to the problems posed by biofilms.

- Categories: