Student Research Offers the Inside Scoop on Dog Poop

Editor’s Note: This is a guest post from Nash Dunn, a writer in the communications office of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences.

When it comes to dog poop, everyone has an opinion.

“It’s gross,” is one common critique. “It’s your responsibility to clean it up,” is another.

And few are as aware of the dog-poop conversation as former NC State graduate student Clodagh Lyons-Bastian.

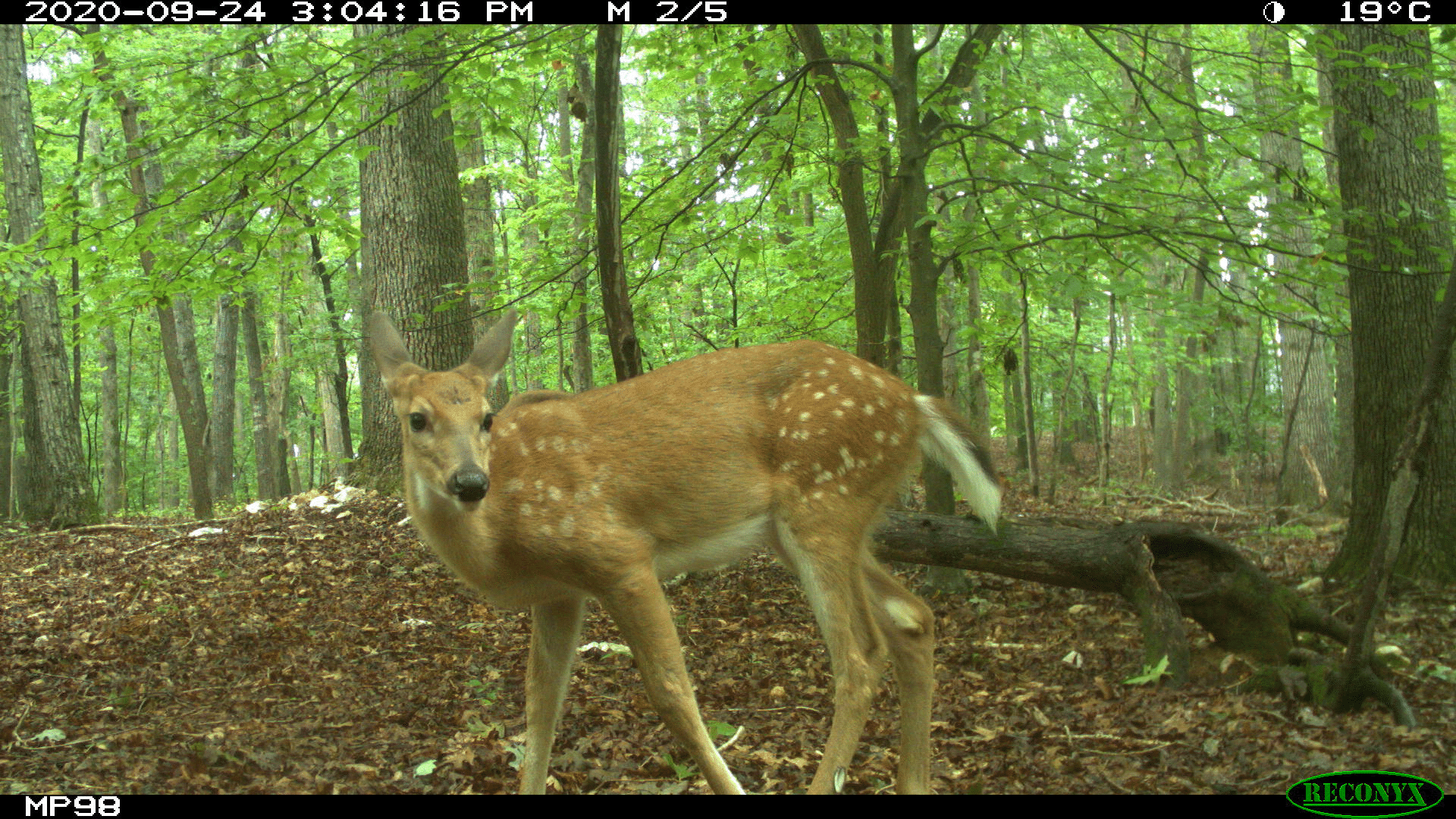

After noticing more and more of her neighbors lamenting about unpicked-up poop, Lyons-Bastian decided to research attitudes and behaviors around dog waste removal while earning her master’s degree in communication. Now the recent graduate and public speaking lecturer is sharing her findings, both with Raleigh-area residents and a municipal advisory board, to help create a cleaner city.

At the core of her study was a citywide survey of nearly 1,000 Raleigh residents, whose responses showed that a lack of resources may be the largest impediment to picking up. In fact, more than 60 percent of respondents said if they didn’t clean up after their pet, it was because they didn’t have a bag or receptacle.

That common response was much different than the one respondents gave for why others didn’t pick up. When asked why they thought their neighbors didn’t remove waste, most respondents guessed it was “too much trouble” or that “no one would notice.”

Lyons-Bastian said that finding is consistent with the fundamental attribution error — a social psychology phenomenon she had studied in her graduate work. The fundamental attribution error occurs when people attribute the action of others to personality traits rather than to external factors that might be at play.

“That in itself shows that there is some kind of disconnect going on,” Lyons-Bastian said. “If people who pick up, and those who don’t pick up, aren’t communicating, an assumption is made that others aren’t doing it out of nastiness and laziness.

“Also, communication could help circulate information about resources,” she continued. “Simply knowing that your neighbor does care would go a long way.”

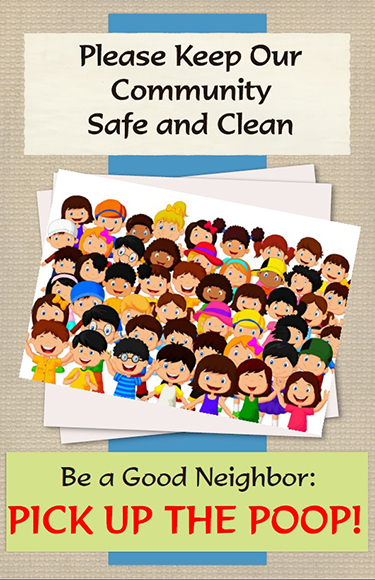

Lyons-Bastian’s research also found that residents are most compelled by positive appeals in signage, such as personal responsibility and community inclusion. Threats and educational information work, she said, but the more specific the better.

“A sign that says, ‘You’ll be fined,’ may not be as effective as a sign that says, ‘You’ll be fined $500,’” she said. “‘Waste spreads disease,’ may not be as effective as a sign that notes a specific disease.”

Lyons-Bastian has presented her findings to citizen advisory councils and other groups throughout the city, and continues to do so. She also shared her study with the Raleigh Parks, Recreation and Greenway Advisory Board, of which she’s a member.

Lyons-Bastian is now creating several prototype signs based on her research that she will make available to the Parks board and neighborhood communities. The next step is to conduct field testing and see where they’d work best in the community. Lyons-Bastian said the advisory board is also considering adding more infrastructure for dogs, such as dog parks and other off-leash areas.

To see the full results of Lyons-Bastian’s study, “The Raleigh Scoop: Attitudes and Behaviors in Dog Waste Removal,” click here.

- Categories: