A History of NC State in Pandemics

Today's novel coronavirus is creating unprecedented challenges for faculty, staff and students. But there's nothing new about NC State's resilience in the face of public health threats.

Two months after NC State opened its doors in October 1889 a global influenza pandemic called “la grippe” swept around the globe over the course of four months — then circled back and did it again over the next two years.

This lesser-known outbreak — which killed more than 1 million people worldwide and may have claimed as one of its victims North Carolina Gov. Daniel Fowle — coincided with improved global transportation by rail and ship.

Even before the invention of cars and airplanes, it moved with the same lightning quickness as the novel coronavirus COVID-19 that is currently encircling the globe and has shut down most nonessential operations in the United States, including most on-campus activities at NC State. Originating in St. Petersburg, Russia, in October 1889, la grippe was first reported in Raleigh less than 10 weeks later on New Year’s Eve.

Statewide, there were 494 fatalities attributed to the disease during the outbreak but the fledgling North Carolina College for Agriculture and Mechanic Arts (as NC State was known then) was located on the remote western outskirts of Raleigh and was mostly spared.

The only reported disturbance, according to March minutes of the inaugural Board of Trustees, was a canceled faculty meeting due to the sickness of two faculty members. There was no reported illness among the 72 originally enrolled A&M students.

Often called the Russian or Asiatic flu in newspaper reports and putative remedy advertisements of the day, it was most commonly known by its ominous-sounding French name.

“It was reported yesterday as coming from a druggist of this city that there was not a family in Raleigh in which there had not been one or more cases of the ‘grippe,’” said the Jan. 30, 1890, edition of The News & Observer. “The ‘grippe’ does not seem to be on the wane. Its worst feature is that nearly everybody who has it has a relapse and a second attack.”

Most of the patients with la grippe in the capital city were treated by Dr. James McKee, Raleigh’s superintendent of health, assisted by his son Dr. John McKee, the physician who served as NC State’s football coach from 1900-1901.

The Spanish Flu Pandemic

There were several other outbreaks of seasonal flu through the years, most notably in 1907, but nothing like the great Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, which claimed more than 50 million lives around the globe and swept through the hallways of NC State College.

The wartime pandemic did not close the school, however, because every student had been drafted into the Student Army Training Corps, which prepared them each as officers for the Army and Navy for the escalating war in Europe.

The flu hit rapidly and with ferocity, beginning in the middle of September. Within four days, the school infirmary, located in what is now Winslow Hall, was overflowing with students and staff. In all, some 450 cases of the flu — more than half of all personnel — were reported on NC State’s campus.

The NC State heroines of the worst infectious outbreak in U.S. history were the 65 female caretakers of frightened young men who were experiencing the dual threats of flu and possible service on the front lines of Europe.

Students at NC State went to class every day, like all the other schools in the state. Eventually, though, all extracurricular activities at State, including five football games and daily marching drills, were canceled, while classes in military arts, engineering and agricultural science continued.

To care for the sick, the university asked for volunteers. Many of the wives and daughters of faculty — including five members of president W.C. Riddick’s extended family — raised their hands. Two of them were counted among the 13,644 North Carolinians who died during the outbreak.

Eliza Riddick, the president’s niece, worked as a receptionist at the college during the day and served in the infirmary at night, along with her mother, aunt and two first cousins. She was described as a woman with “a frank, friendly disposition” and was remembered after her death on Oct. 17, 1918, as a “volunteer martyr-nurse.”

Lucy Page was a professional nurse in Raleigh who contracted the flu, recovered and returned to work at the college infirmary, then died after contracting the disease again during its second wave through Raleigh.

A total of 13 students died from the flu. Their story is told in this NC State alumni magazine story from 2018. More about the 1918 pandemic from the NC State Libraries Special Collections Archive is available online.

There were other flu outbreaks over the years. In December 1928, an outbreak throughout the South forced NC State and UNC-Chapel Hill to cancel the last week of the fall semester, sending students home early for the holiday break. Students came back to school on Jan. 2, 1929, after a three-week break, did two days of course review from the fall semester and then took final exams, something that did not sit well with the student population.

NC State was the first school in the South to close because of the epidemic, but other colleges in North Carolina, Virginia and Georgia followed suit. Carolina also ended its classes a week early — the first time the university closed its doors since it was shut down for four years during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

In the winter of 1936, another flu and cold epidemic swept across the state, forcing NC State and UNC to postpone their second basketball game of the season, while most other winter sports such as boxing and wrestling and all intramural sports were canceled. State baseball games against UNC, Florida, Richmond and Maryland were also canceled because of the Southern flu outbreak, as well as other spring sports.

Polio Scares of the 1950s

Shortly after the Texas football team came to Chapel Hill and beat the White Phantoms 28-7 in the 1952 season-opener, UNC fullback Harold “Bull” Davidson of Murphy was diagnosed with acute infantile paralysis, or polio. North Carolina quickly canceled its next two games, at Georgia and against NC State in Chapel Hill, at a cost of about $355,000 in ticket sales alone.

The university suspended all varsity athletics and intramural sports activities for two weeks, “as a means of safeguard and precaution for protecting its opponents’ players as well as its own.”

Davidson was one of five athletes among UNC’s 5,700 student population diagnosed with the disease. Cross country runner Richard Lee “Dick” Bostian, son of NC State Chancellor Carey Bostian, was among them, along with three other athletes.

NC State and Georgia quickly negotiated a game against each other to make up for the lost contest, though it was not exactly easy. Georgia had only one available date, which coincided with NC State’s game the next week against Davidson College.

Davidson players voted not to move their game with the Wolfpack, forcing State College officials and athletics director Roy Clogston to arrange what would have been the wildest doubleheader in college football history. The team’s starters were to be flown to Athens, Georgia, on Friday night to play an afternoon game against the Bulldogs on Saturday, Oct. 4, 1952, then board a charter flight back to Raleigh for a night game against the Wildcats.

In the end, Davidson relented and moved the game with the Wolfpack to the following week. Georgia punished the Wolfpack 49-0 and fullback Alex Webster was carried off the field on a stretcher. The next week, State beat Davidson 28-6.

It was the last disruption in the NC State-UNC rivalry that now has been played 68 consecutive years.

Two years later, Florida State flew to Raleigh for a game on Oct. 16, 1954, during what turned out to be Florida’s largest polio outbreak of the decade. Other colleges and high schools canceled games and were out of school for the outbreak, but the Seminoles left Tallahassee before any restrictions were in place.

They arrived in Raleigh just as Hurricane Hazel, a Category 4 storm that was the state’s worst natural disaster until Hurricane Fran hit in 1996, blew through Raleigh and knocked the roof off the Riddick Stadium press box. The game was played anyway, with FSU recording a 13-7 upset.

Players for both teams were monitored for symptoms afterward, but none developed the disease and other students were not affected.

Statewide Red Measles Scare

During the winter of 1989, the middle of the state was overcome by the first significant outbreak of rubeola, or red measles, in decades. While most of the state’s cases were concentrated in Rowan and Cabarrus counties — where schools and all extracurricular activities and sporting events were canceled for the winter — measles eventually spread to 60 of the state’s 100 counties, with a total of 167 confirmed cases.

After an NC State student living in Bragaw Residence Hall was diagnosed with the measles, the Wake County Board of Health enforced a two-week quarantine to prevent the spread. Students and staff without proof of immunization during that time were not allowed to attend classes and were threatened with removal from dormitories until they received a shot or could prove they had been vaccinated.

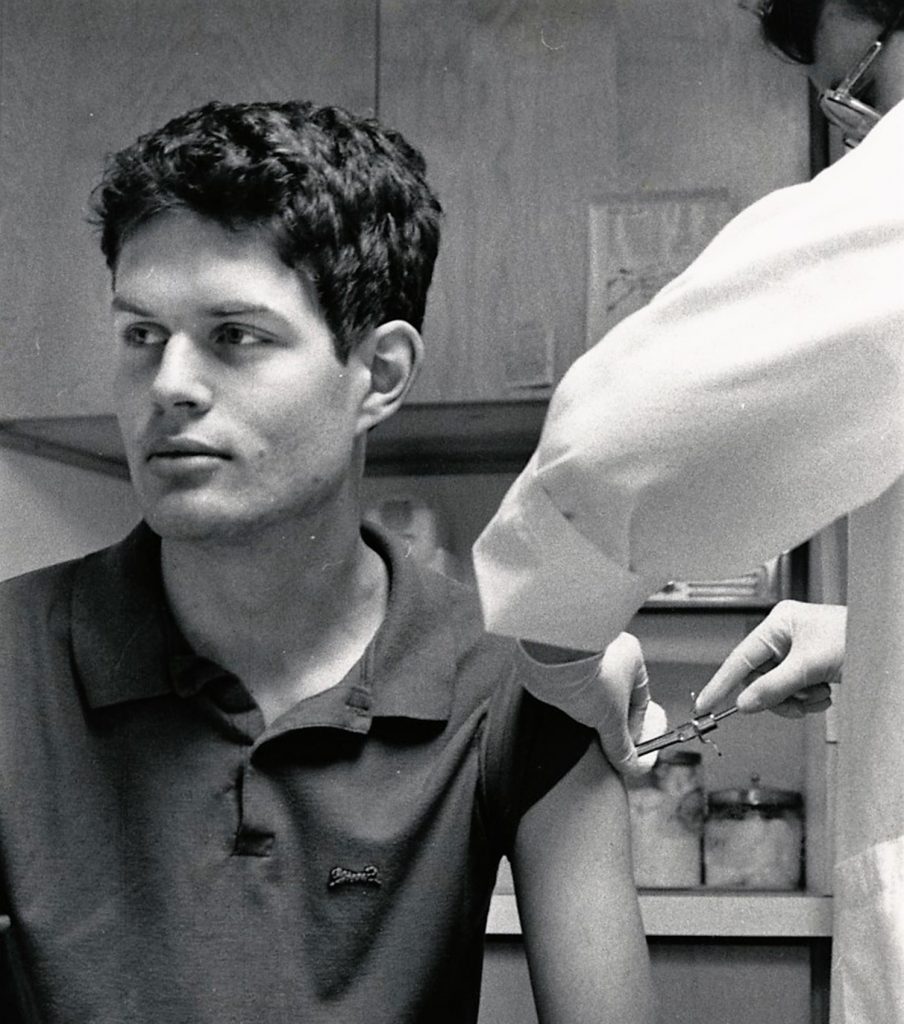

Student Health Services set up a hasty week-long immunization clinic in Talley Student Union to give free vaccination shots to more than 13,900 students, faculty and staff who did not have immunization records, at a cost of nearly $125,000 to the Wake County Health Department.

NC State, however, paid for the overtime for permanent staff who worked longer shifts throughout the mandatory vaccination period. No other cases of the red measles were reported after the two-week quarantine.

Unprecedented Response

For now, NC State’s campus is on reduced operations due to the COVID-19 outbreak, an unprecedented response to an emerging disease that has claimed thousands of lives worldwide.

However, the campus has survived larger and greater threats through the years from disease and war, and come through with sustained periods of growth. And, as the 1989 quarantine proved, sometimes an abundance of caution against an invisible foe is the best way to overcome it.

- Categories: