Life Blood: Why I Donate Platelets

In a first-person account of his experience donating platelets, Jeff Braden describes how a once-foreign concept transformed into an act of service — and why he continues to give during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Voices is a new series of first-person narratives written by members of the NC State community reflecting on experiences that have shaped their personal and professional lives. Jeff Braden is dean of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences and a professor of psychology.

It was an offhand remark one of my friends made when I lived in California in the 1980s that got me started making platelet donations.

I’d given blood in the occasional blood drive in college and continued to do so sporadically afterward. When I asked my friend if he was going to participate in an upcoming blood drive at our synagogue, he shook his head. I was surprised; this guy was always the first to show up to help at a food drive, or to volunteer for our annual day of service. When I asked him why he wasn’t giving, he explained it would keep him from being an apheresis donor.

I confessed I didn’t know what apheresis donation was, and he explained it was extracting platelets (and sometimes plasma) from blood, and then returning the remaining fluid back to the donor. In contrast to giving whole blood, which requires a minimum of six weeks between donations, platelet donors can give just a few days apart.

He also mentioned that hospitals are more often in need of platelets than whole blood, in part because the donation process is longer and more complicated.

I was intrigued, skipped the blood drive, and went with him the next time he donated platelets.

An Unexpected Benefit

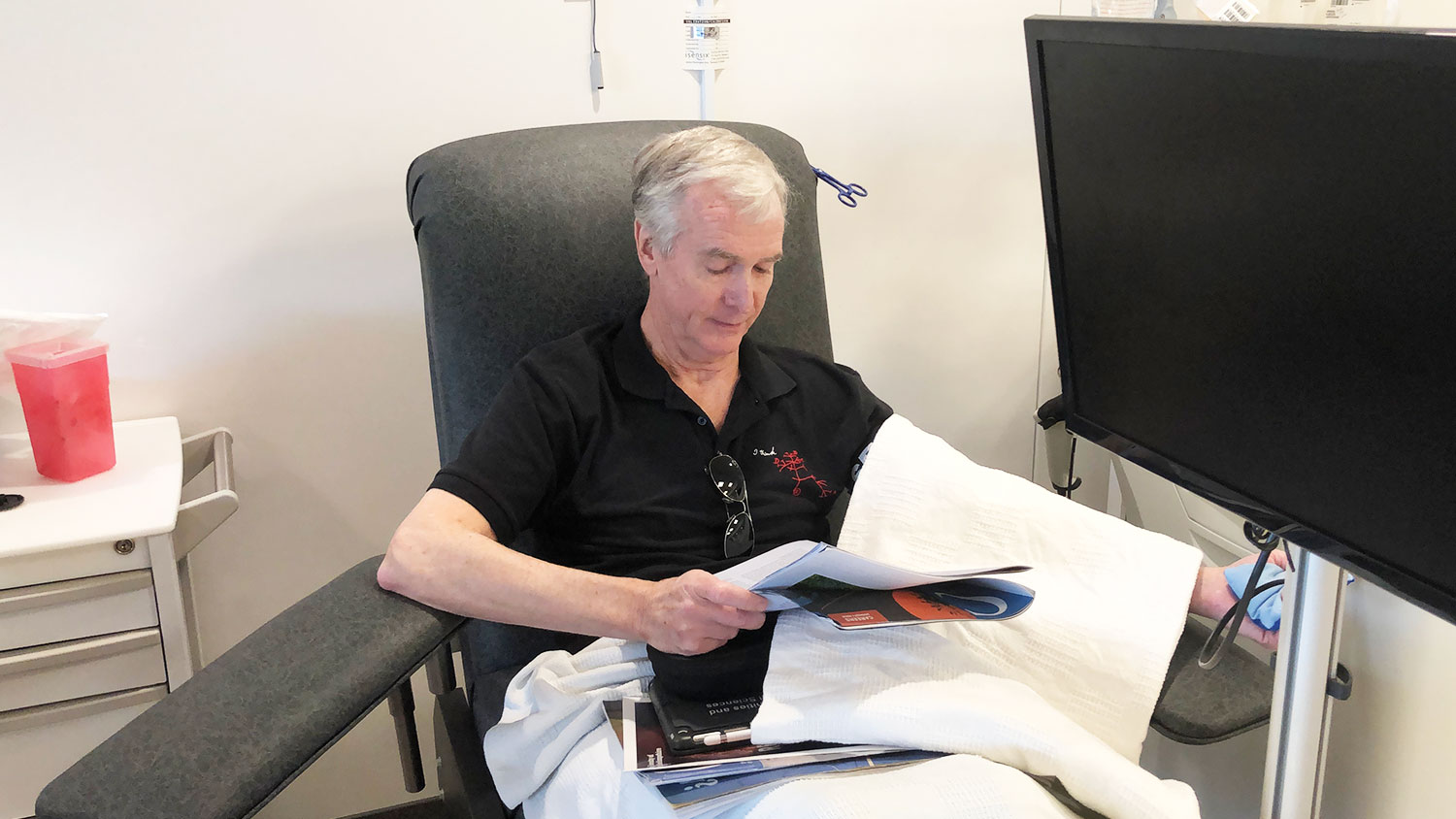

The first tipoff that apheresis donation would be different was the time. Whereas typical whole blood donation takes about 45 minutes altogether, our appointment was three hours long, not including the time to complete the pre-screening and the post-donation recovery period.

Donation at that time also required two needles, one in each forearm. One needle took out whole blood, which ran through a machine with a centrifuge to remove the platelets, and the other needle returned the remaining liquid back into the other arm. This was well before the days of flat-screen displays and on-demand content, so I brought a book. Turning the pages as I read was awkward, given the needles in each arm. Still, I didn’t mind the pain of the needle going in nor the discomfort of them staying there as I completed the donation.

The best part of the donation was that, after donating, I didn’t experience the lightheadedness and mild dizziness I often felt with whole blood donation. I decided then and there that apheresis donation would become a regular part of my life, as it didn’t bother me much and forced me to keep up with my reading.

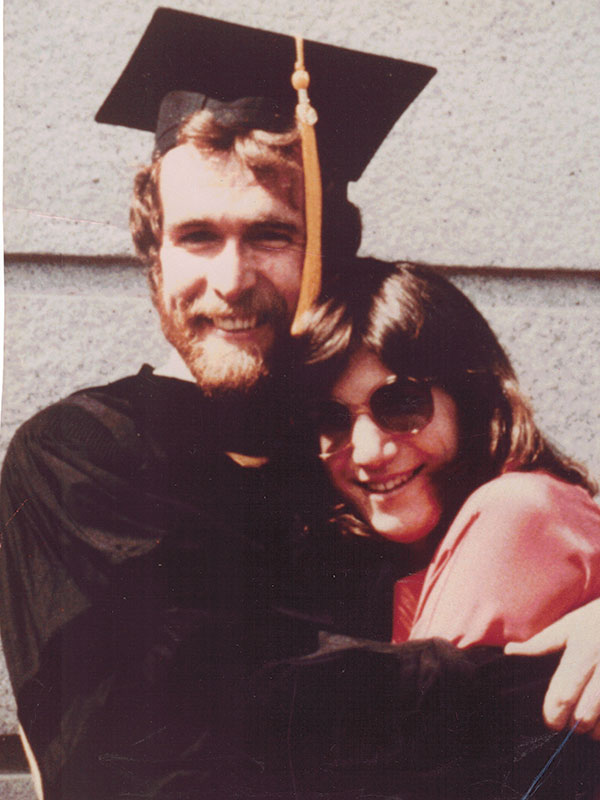

Although I was working full time as a school psychologist at the California School for the Deaf, I was also working on my Ph.D. at Berkeley — and as any graduate student will tell you, you never have enough time to read everything professors assign. Apheresis donation was a two-fer: I did a mitzvah (good deed) and caught up on reading, too.

with his wife Jill at his graduation from UC Berkeley in 1985, started donating platelets while pursuing his Ph.D. there.

Giving to Save a Life

As I began my career as a professor and started a family, my donations were more sporadic. I learned, however, that making an apheresis donation when I moved to a new community is a quick way to make local friends. Because apheresis donors are generally rare, blood donation centers go out of their way to welcome you — and they keep calling you back when they need more platelets.

Still, it was a sporadic habit — until I realized how much donations could mean to a family.

After I spent four years as an assistant professor at the University of Florida, my wife, daughter and I moved back to California in the late 1980s. My daughter became friends with another girl in our new neighborhood. We soon learned that my daughter’s friend had a form of leukemia that required intensive treatment with chemotherapy, steroids and a host of interventions.

One of the things she needed was A+ platelets and plasma from a cytomegalovirus negative donor. As it happened, I fit both of those characteristics. I began giving when she needed donations (about twice a month).

I’m happy to say that my daughter’s friend survived. Indeed, she is now considered cured — a word I didn’t associate with leukemia until I was middle-aged. In the process, I learned much more about apheresis donation and its importance to medical treatment and health.

Why Donate?

Apheresis is broadly described as the removal from whole blood of one or more components. The most common component to remove is platelets, the cells in blood that form clots to stop bleeding. As such, they are critically important in the treatment of cancer, chronic diseases and traumatic injuries.

It’s estimated that, on average, somebody in the United States needs platelets every 15 seconds.

However, unlike whole blood, platelets have a relatively short shelf life; they must be used within five days of donation. A typical donation produces enough platelets to help up to three patients. Occasionally, donors will be asked to also donate plasma (red blood cells) if there’s a specific need for their blood type.

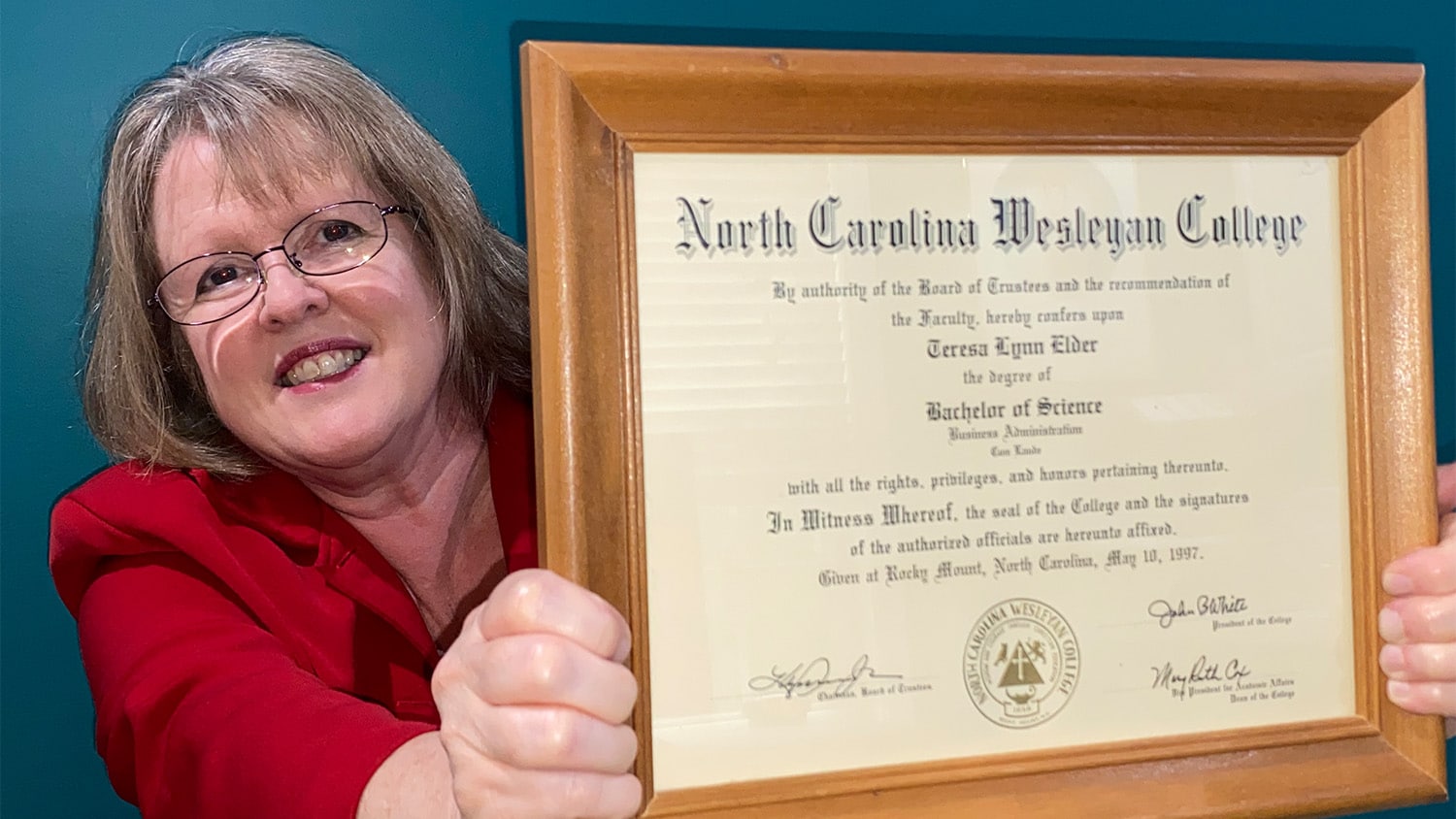

Donations now use a single needle in one arm and take a total of about three hours (including the 30 minute pre-screening). Most donation centers also provide on-demand video or allow a donor to bring their own device to binge-watch that must-see series. I still tend to use donations as an opportunity to catch up on reading (usually a stack of Chronicle of Higher Education issues).

I also got in the habit of scheduling my next monthly donation before I leave the donation center. Medically, I could give more often, but practically, once a month works best for me.

As a result, I’ve donated in excess of the equivalent of 20 gallons of whole blood since I moved to Raleigh — and that’s even after I had to stop donations for a year after visiting sites with malaria (including Africa, India and South America).

Continuing During COVID

My monthly donation pattern was pretty well set — until COVID-19 came calling. I struggled with whether to continue to make donations: On the one hand, I’m in a high-risk group (I’ll just say I have a Medicare card and leave it at that). On the other hand, medical needs don’t vanish just because there’s a pandemic.

The demand for platelets has declined — in part due to less driving (fewer accidents) and cancelation or delay of surgeries — but it hasn’t gone away. People still have cancer, chronic diseases and accidents.

I’m happy to say that the center where I donate has become much more deliberate in scheduling donations so that they are sure the platelets or other products they collect will have a use. I’ve just scheduled my next donation; depending on need, I’ll schedule another one when I’m there.

I’m a psychologist, and I appreciate the role of habits in shaping behavior (habits are what people do when nobody’s looking). I’m in the habit — and unlike most donors, I’m blessed to have first-hand knowledge of the difference these donations make to those who receive them.

- Categories: