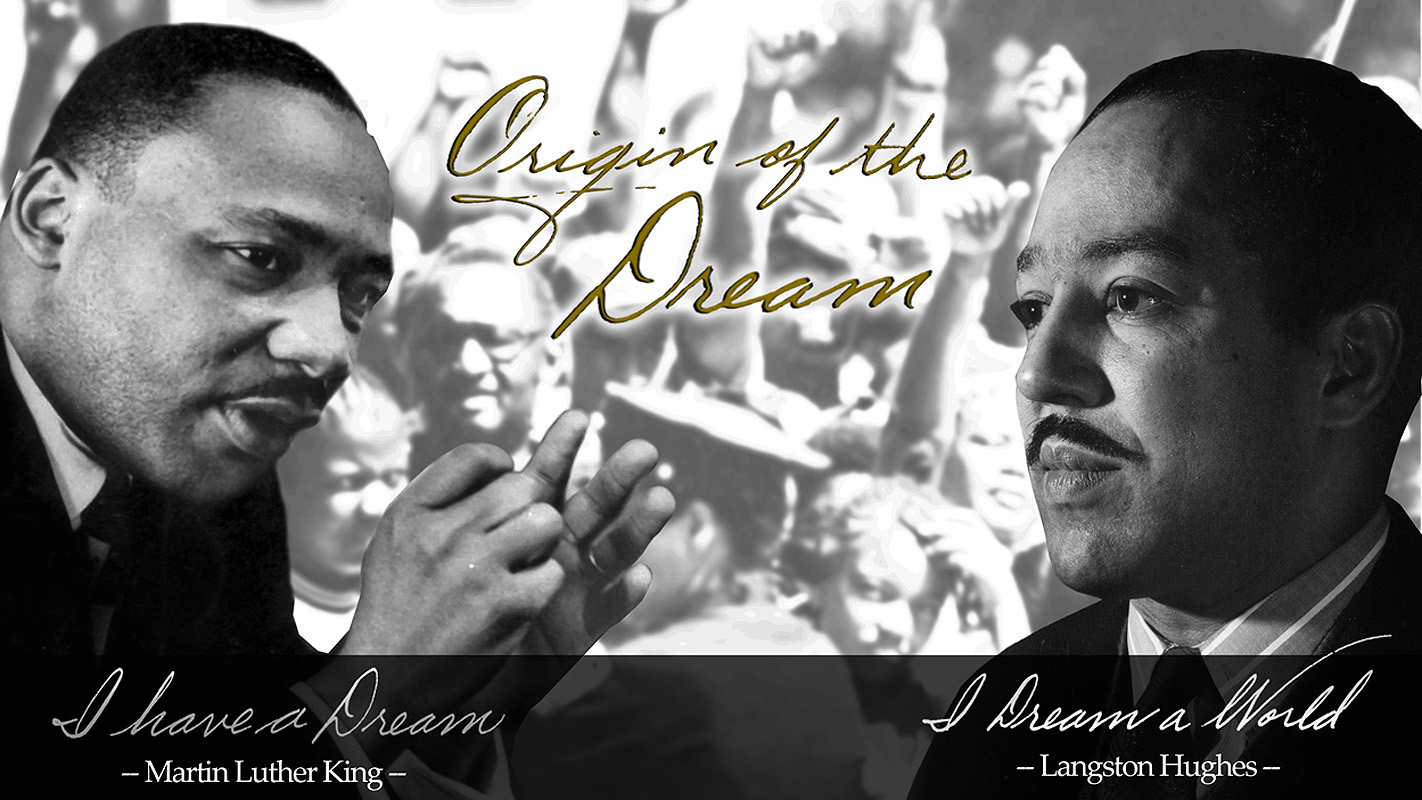

In his new book Origins of the Dream, NC State English professor Jason Miller makes a tangible connection between the long suspected but never proven link between the poetry of Harlem Renaissance hero Langston Hughes and the prose of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.

This is Miller’s second book on the poetry of Hughes. His first, Langston Hughes and American Lynching Culture, was published in 2011. Miller, a former college basketball player at Division II Nebraska-Kearney, has been an associate professor of English at NC State since 2005.

Miller will promote his new book with several appearances on and off campus during Black History Month. On Feb. 10, he will speak at the Hunt Library auditorium at 7 p.m. and appear on the local NBC show “My Carolina Today” at 11:30 a.m. On Feb. 19, he will host a signing event at Quail Ridge Books in the Ridgewood Shopping Center off Wade Avenue.

In advance of Monday’s Martin Luther King holiday, Miller answered five questions about his newest publication, which is now available through the University Press of Florida.

Q. What led you to become a Langston Hughes scholar?

A. After I finished college, I spent five years as a high school English teacher. One of the most interesting and accessible poets that students reacted to was Hughes. So I used him in the classroom because I had this connection with him through blues music and jazz. We talked about how his poems had this great blues influence. When I went back to graduate school and began working on my doctorate in 2000 at Washington State University, I realized that I had been working with a really old collection of Hughes’s poems. In 1959, he published just selected poems, and because of the political climate at the time, none of his controversial or challenging works were in there. As an undergraduate and high school teacher, I thought I had known his poems. But it really wasn’t until 1994 that his entire oeuvre of poems was brought together that I started seeing all these shocking and challenging poems that I had never seen before. Through my re-reading, I found the linkage that is the basis for Origins of the Dream.

What made you want to explore that linkage?

About three-fourths of the way through the research for my first book on Hughes, I saw a couple people mention that maybe Martin Luther King’s use of dream imagery came from Hughes’ poems. In October of 2007, I walked to the fifth floor of the D.H. Hill Library and started going through all the King books. The first one I picked up was The Trumpet of Conscience and it is a collection of sermons King gave at the end of his life. I started flipping and came to page 76. On the left side, about halfway down this Christmas Eve sermon in 1967, it says “I am personally the victim of deferred dreams, of blasted hopes.” Obviously, “Dream Deferred” is one of the signature poems of Langston Hughes. So I told myself that there was definitely something to it, because this was just a few pages into the first book I looked at. That began the process of this particular book. What the book does is track back the shift from dreams as a negative from the Langston Hughes poems to something that is positive that King used in his speeches. That actually occurs on Nov. 27, 1962, which happened in a sermon in Rocky Mount, N.C. That’s when he first used the words “I have a dream…” It might be the best speech he ever gave. I have it on audio and it is 55 minutes long.

In what ways did their experiences align?

I did a scrolling timeline of every speech King gave from 1956 through the end of his life in 1968. I came up with every connection–political, cultural, topical—that I could. One of the things I found was that the first time King alluded to “dream deferred” in a sermon was on April 5, 1959, just after “A Raisin in the Sun” opened on Broadway. It was the first time he ever talked about dreams. What he said was, “Who here has not been the victim of blasted hopes and shattered dreams?” He’s playing with Hughes’ words, but what is important is that dreams at that time were not hopeful or aspirational or inspiring. They were “blasted.” King turns it all upside down and turned dreams into something positive and hopeful. People who study King look at his religious aspects, his historical importance, his sociological importance or his philosophical studies, but no one looks at his literary influences. That’s the reason this direct linkage has escaped notice all these years.

Why is all of this relevant today?

I’d say there are three things. First, we rarely ever think about the role poetry plays in politics. We often segment the two and keep them separate. To see King’s own engagement in poetry … is quite remarkable.

Second, when we think of Langston Hughes, we think of him as someone from the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and ‘30s. Few people even realize he died less than a year from King’s assassination. These two met, they exchanged letters; Hughes, at King’s request, wrote a personal poem for King. I would argue that Hughes’ poetry is as important to the civil rights movement as it is to the Harlem Renaissance.

Finally, the dream of King has come to embody just about everything about him. There are many reasons for that. To have background and understand where that dream came from, how it developed and an understanding of its roots, illuminates not only King’s speaking and talking, but some of his deepest values.

Some of King’s biggest ideas of what the world should look like have this overlap with Hughes. It’s part of his whole world view. He masterfully embraced as many different things as he could. He unified politics, he unified prophecy and he unified poetry when he enunciated his dream. He also captured capitalism’s idea of the American Dream, the Christian idea of being a dreamer and, as you get to know the full extent of Hughes’ works, perhaps even a subversive communist angle on the world that things should be shared equally. One of King’s greatest accomplishments is to unify. It’s important to see all those things together.

In the final analysis, was King inspired by Hughes or were his thoughts and speeches direct derivatives of Hughes’ original works?

My sense is that King actively engaged in Hughes’ poetry, internalized it, rewrote it and it eventually became his own. For me, it’s a complex process. What I think is fascinating is to know how much King knew and had regard for Hughes’ works. King one told a group of students at Spelman College, “Originality is never creating something new. If that were true, Shakespeare was never original. Originality comes with giving new validity to old forms.” And that’s what King did with Hughes’ work.

- Categories: