Rendezvous With History

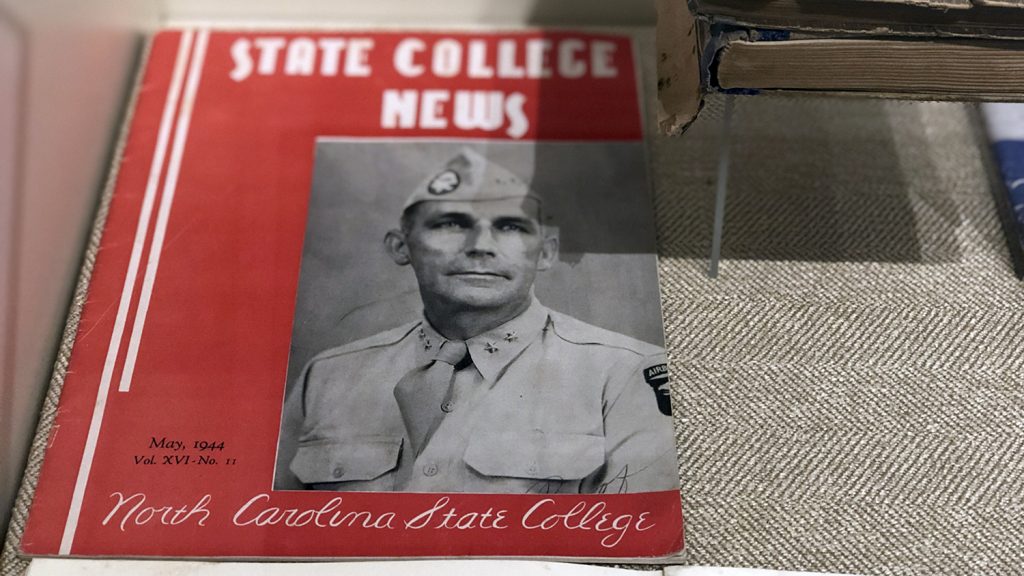

NC State alum William Carey Lee, 'Father of the U.S. Airborne,' trained the elite paratroopers dropped behind German lines during the Allied invasion of Europe on D-Day. A museum in Dunn, North Carolina, honors his life, service and athletic accomplishments at Wake Forest and NC State.

Early on a cloudy morning, they jumped into darkness to save the world.

They didn’t know what waited for them below — many would die before their feet hit the ground or shortly thereafter — but they were duty-bound and determined to carry out the mission most of Europe had been awaiting for half a decade.

And the last words on their lips were the name “Bill Lee,” who went from his family’s Harnett County farm to both Wake Forest and NC State to become one of the nation’s most innovative military leaders. He was hand-picked by Gen. Mark Clark to plan the U.S. Army’s Airborne Command. He had every intention of being in the first wave of the 101st Division Screaming Eagle paratroopers that jumped behind enemy lines at 12:48 a.m. on the Normandy coast on June 6, 1944.

Instead, NC State alum Gen. William Carey Lee sat at the desk at his home, listening to news reports on his Zenith tube-style radio, his devoted wife Dava by his side. Lee suffered heart attacks in February and March of 1944 while preparing for his life’s crowning achievement. Military doctors prohibited him from joining his paratroopers on D-Day, sending him back to Dunn on May 30.

He could only hear the “rendezvous with history” he had promised his division when it was formed in 1942, instead of leading it.

“He never got to jump into glory,” says Mark Johnson, curator of the General William C. Lee Airborne Museum, which is located in Lee’s three-story brick house just a few blocks off Interstate 95, about halfway between Raleigh and Fayetteville. “He had that rug snatched right out from under him.”

For years, Lee’s division of well-trained paratroopers were militarily controversial, modeled after German parachutists that Lee studied while serving in Europe in the 1930s. President Franklin Roosevelt and his old guard staff had little use for the pioneers of the Airborne Command, but British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was intrigued after seeing Lee’s troops in action at Camp Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina.

When General Dwight D. Eisenhower planned Operation Overlord, which celebrates its 75th anniversary on Thursday, the paratroopers and airplane gliders were a key component of the surprise attack. They were charged with securing the bridges behind the Normandy beaches, preventing reinforcements from coming to the aid of the German artillery batteries already hunkered into machine gun nests on the beach, and allowing the Allied invaders who made it off the beaches a safe route to France’s interior.

Cloudy conditions created chaos in the nighttime sky, but the thousands of troops Lee had trained and developed accomplished their mission that night and continued to provide support as the Allies charged through Belgium, the Netherlands and into the Battle of the Bulge in the war’s crucial final months.

Son of the Sandhills

Lee was a simple son of the Sandhills when he left Dunn in 1913 for Wake Forest College, the school of choice for generations of Baptists like Lee and his family. Lee excelled at football and baseball, but decided to transfer to the North Carolina School for Agriculture and Mechanic Arts (now NC State) after two years because Wake had no ROTC military training programs.

Lee starred in both sports for the Farmers, but left before graduating in 1916 to become a military instructor at Turlington Academy, before enlisting in the U.S. Army in June 1918 for the final days of World War I. He returned to NC State as a military instructor and head of the ROTC program from 1922-26. Through his work in Panama and Germany, he became friends with fellow Sigma Nu fraternity member George Marshall, who play a key role in advancing Lee’s career.

Eventually, through summer school and correspondence courses, Lee earned his NC State degree in 1936.

Three weeks after V-E Day, Lee was presented an honorary Doctor of Military Science by Chancellor John Harrelson, also a veteran of both world wars, at the school’s May 25, 1945, commencement exercises.

Lee’s stressful but accomplished life ended at the age of 53, when he died on June 25, 1948, in his home in Dunn. He was buried with full military honors at Greenwood Cemetery, a few dozen blocks from where he was born.

The museum in his family home, dedicated on June 6, 1986, honors his life, military career and athletic accomplishments at both NC State and Wake Forest. Along with displays of his uniforms, early parachutes and other military artifacts, there is a modified molded Riddell football helmet that Lee and his paratroopers used as a makeshift safety device.

It’s one of the many things Lee took from his college career as he left home to do his part to save the world.

- Categories: