Black Bear Gut Biome Simpler Than Expected, Scientists Say

For Immediate Release

In recent decades, researchers have found that most mammals’ guts are surprisingly complex environments – home to a variety of microbial ecosystems that can profoundly affect an animal’s well-being. Scientists have now learned that the bear appears to be an exception, with its gut playing host to a microbial population that varies little across the intestinal tract.

“It’s the first mammal species where we’ve looked at two separate locations in the gut and found microbial communities that are essentially indistinguishable from each other,” says Sierra Gillman, first author of a paper on the work and a Ph.D. student at the University of Washington. Gillman did the work while a grad student at Northern Michigan University (NMU).

“Bears have really simple guts – pretty much a garden hose – so they can’t regulate their gut microbes to the extent that animals with longer, more complex guts can,” says Erin McKenney, co-author of the paper and an assistant professor of applied ecology at North Carolina State University. “Without that control, the bears’ diet and environment may play a greater role in shaping the gut microbiome. It raises some interesting evolutionary questions about the relationship between the shape of an animal’s gut, its gut microbiome, and the relationship between the microbiome and the animal’s health and behavior.”

The researchers set out to learn more about the gut microbiome of American black bears (Ursus americanus) with little idea of what to expect. Not much research has been done on microbial ecosystems in the species, and what work has been done has focused on animals in captivity. Since animals in captivity and animals in the wild often have very different gut microbiomes, the researchers were curious as to what they’d find. One major challenge was obtaining samples in the first place.

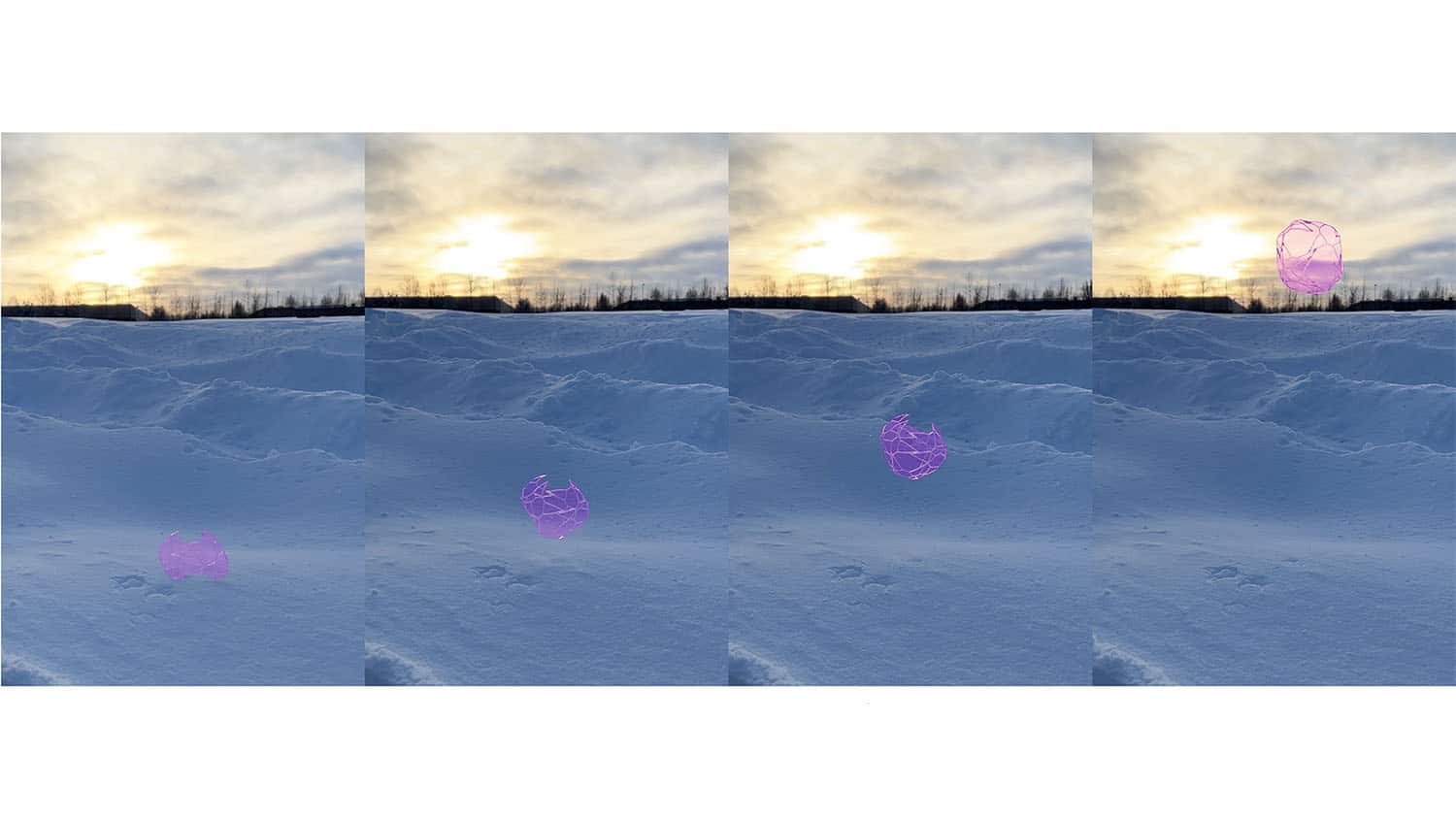

To that end, the researchers worked with guides who lead scheduled trips with hunters in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Gillman developed a detailed set of protocols and conducted training sessions with the guides on how to collect samples from bears that were harvested when the guides went on their regularly scheduled trips with hunters. Specifically, Gillman taught the guides how to retrieve samples from both the jejunum, which is the middle section of the small intestine, and the colon, which is also called the large intestine.

Ultimately, the researchers obtained 31 useable jejunum samples and 30 useable colon samples. They then analyzed the samples to identify which microbial species were present.

The researchers expected to see more, and different, species of microbes in the colon. The colon is often where digestion slows down, enabling gut microbes to break down fiber in the diet – which normally fosters microbial diversity. But not, apparently, in the black bears of Michigan.

Why are bear gut microbiomes different from the microbiomes of other omnivores scientists have looked at? In a word, it’s probably the cecum.

Omnivores with more complex guts have a small pouch – called the cecum – between the small and large intestine. The cecum helps slow down the rate at which food passes through the gut, like an oxbow in a river, and likely serves as a reservoir for microbial populations in the gut, allowing animals to replenish the diversity of their microbiomes, even as their diets and health change.

“Bears don’t have a cecum,” Gillman says. “That makes their gut microbiomes more vulnerable to systemic change due to diet, health or other factors.”

This finding has an immediate practical application for wildlife researchers.

“In many animal species, a fecal sample can tell you what the microbial diversity of the colon was like – but it doesn’t tell you much about what’s happening in other parts of the gut,” says Diana Lafferty, co-author of the paper and an assistant professor of wildlife ecology at NMU. “Our work suggests that a fecal sample offers insight into the microbial community across the entire gut for black bears – and possibly for other carnivores and omnivores that have simple gut morphologies.”

In other words, they can learn more from wild animal poop than they previously thought.

The researchers are currently in the process of comparing the samples collected in Michigan to samples from black bears harvested by hunters in North Carolina, in order to determine if the findings are consistent across geographic regions.

“We are also looking at carnivore species that also lack a cecum to see if they have a similar lack of microbial diversity across the gut,” Gillman says.

“And we are working on a project that will help us better identify and understand the connections between the gut microbiome and bear health,” says Lafferty.

“One of the things we’re curious about is weight gain,” McKenney says. “We know that specific shifts in the microbiome can lead to weight gain and obesity in other species, which is usually viewed as a negative. But for species that hibernate, like bears, that could actually be advantageous.”

The paper, “Wild black bears harbor simple gut microbial communities with little difference between the jejunum and colon,” appears open access in the journal Scientific Reports.

The work was done with support from the National Science Foundation, under grant number 1000263298; and from Sigma Xi, the scientific research honor society, under grant number G2018100198233997.

-shipman-

Note to Editors: The study abstract follows.

“Wild black bears harbor simple gut microbial communities with little difference between the jejunum and colon”

Authors: Sierra J. Gillman and Diana J. R. Lafferty, Northern Michigan University; Erin A. McKenney, North Carolina State University

Published: Nov. 27, Scientific Reports

DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-77282-w

Abstract: The gut microbiome (GMB), comprising the commensal microbial communities located in the gastrointestinal tract, has co-evolved in mammals to perform countless micro-ecosystem services to facilitate physiological functions. Because of the complex inter-relationship between mammals and their gut microbes, the number of studies addressing the role of the GMB on mammalian health is almost exclusively limited to human studies and model organisms. Furthermore, much of our knowledge of wildlife–GMB relationships is based on studies of colonic GMB communities derived from the feces of captive specimens, leaving our understanding of the GMB in wildlife limited. To better understand wildlife–GMB relationships, we engaged hunters as citizen scientists to collect biological samples from legally harvested black bears (Ursus americanus) and used 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing to characterize wild black bear GMB communities in the colon and jejunum, two functionally distinct regions of the gastrointestinal tract. We determined that the jejunum and colon of black bears do not harbor significantly different GMB communities: both gastrointestinal sites were dominated by Firmicutes and Proteobacteria. However, a number of bacteria were differentially enriched in each site, with the colon harboring twice as many enriched taxa, primarily from closely related lineages.

- Categories: