War and Remembrance

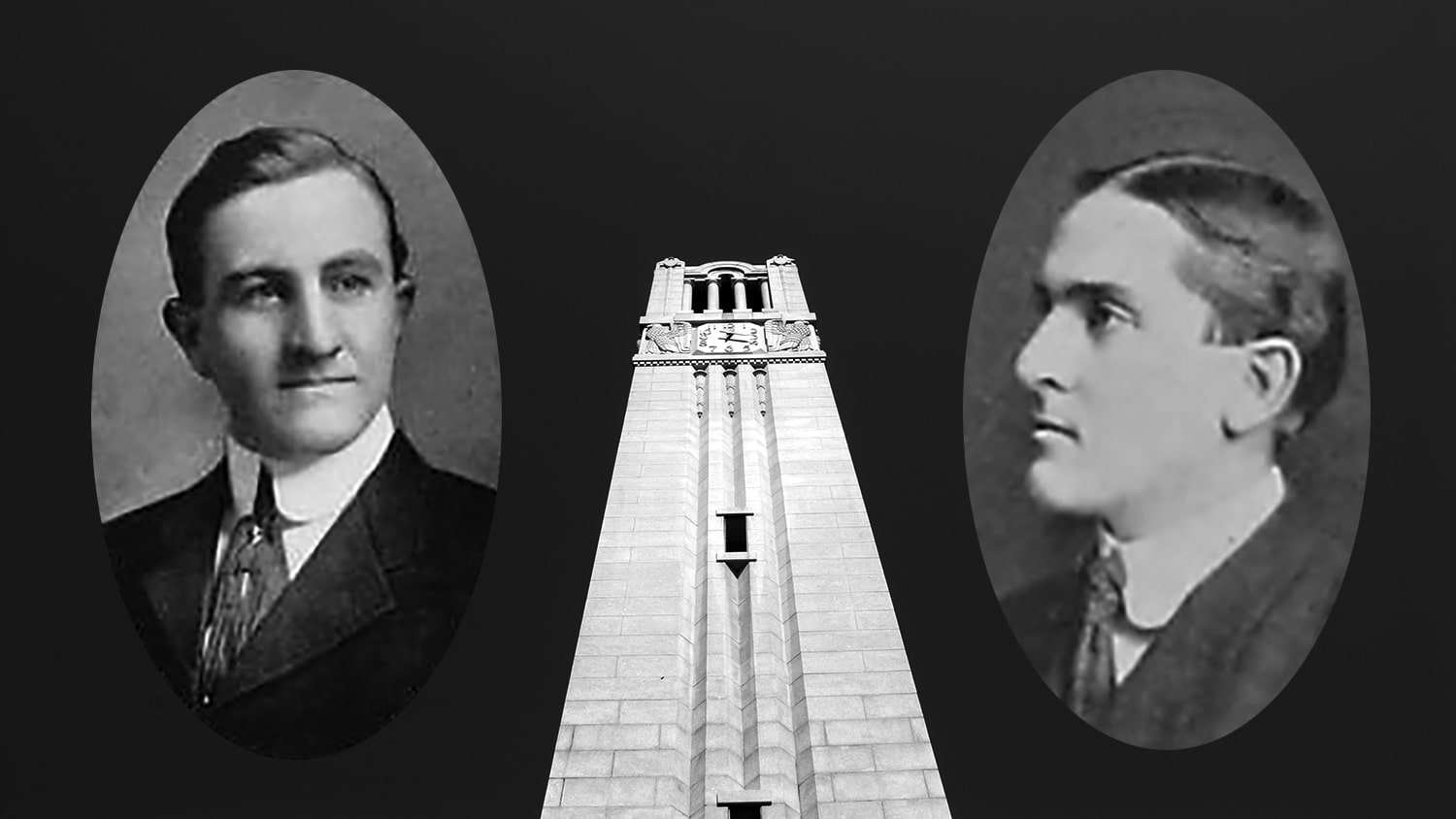

Friendship and sacrifice laid the foundation for NC State's Memorial Tower. Learn the story that inspired the university's iconic Belltower.

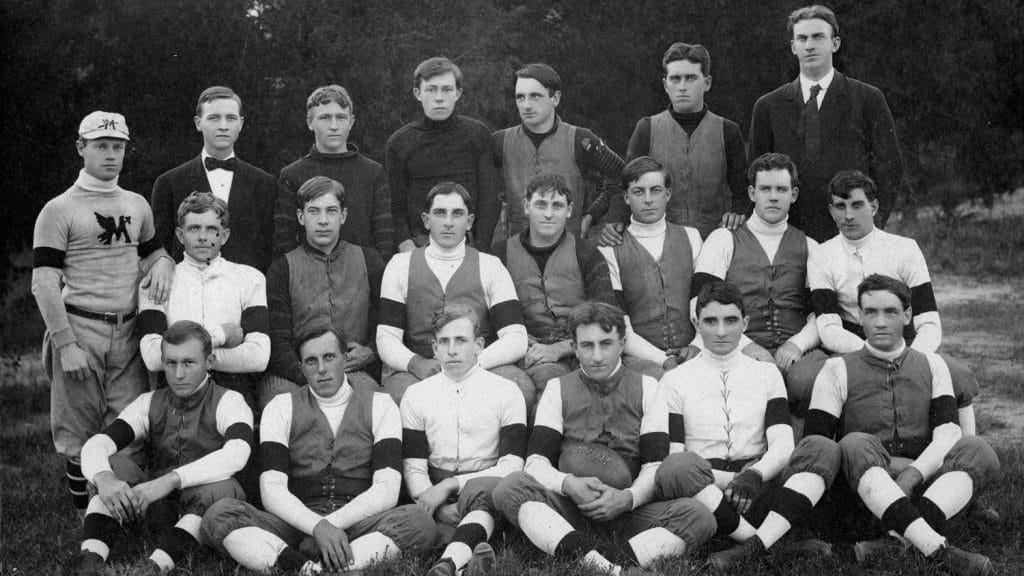

They forged a friendship on the scruffy grass now known as Pullen Park’s Red Diamond Field and the old North Carolina State Fairgrounds near the modern NC State campus, an older student and a young buck playing on the left side of the football team’s offensive line.

At the age of 25, tackle Vance Sykes must have seemed like a grandfather on a team of players as young as 16. From the Orange County community of Eflin, it took a while for this son of a tobacco farmer to light out for Raleigh to study civil engineering at the North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts, which was not even 15 years old when he arrived in the fall of 1903 as part of a 125-member freshman class.

He was older, perhaps wiser, than young end Frank Martin Thompson, a Raleigh boy with tremendous athletic skills that were obvious from the time he transferred from faraway Davidson to enroll in his hometown school in 1905.

They played together just two seasons, 1905 and ’06 for one-year coaches George Whitney and Willie Heston. They won seven games, lost only twice and participated in five tie games back during the dangerous flying wedge era of college football.

They became lifetime friends.

The symbol of that friendship — and the memorial for all NC State students and alumni who died fighting in and training for World War I — towers over Hillsborough Street, now surrounded by a lovely new plaza and, for the first time, sporting the bells it was designed to house.

The Memorial Tower, which will be rededicated with a virtual ceremony on Friday afternoon, was Sykes’ idea.

A War Hero

After graduating in 1907, Sykes took a one-year position as a mathematics and civil engineering instructor. He soon left, however, to begin a lifelong career with the Seaboard Air Line Railroad, the East Coast lifeline that connected the emerging cities of the South at the turn of the 20th century.

He bounced from Atlanta to Savannah, Georgia, to the small town of Hamlet, North Carolina, in Richmond County, where he set roots with his wife and raised his only daughter.

Thompson, who graduated with a degree in textiles in 1909, stayed rooted in Wake County for what turned out to be a prodigal coaching career that included success, betrayal and, ultimately, redemption in the eyes of his classmates. After completing his successful athletics tenure as captain of both the baseball and football teams at A&M College, he took over as the school’s permanent baseball coach while still a student.

Thompson “has won the distinction of being the best all-around athlete of the ’09 class, by hard, consistent work and gritty determination,” said the Agromeck. “Rather bashful and consequentially apparently indifferent to the wiles of women, but very much admired by femininity, and we are sure that he would make just as much of a heart smasher as he is a line smasher if he but tried.”

He left in 1912 to give professional baseball a try, but by then the former catcher had lost a little speed with his bat and accuracy with his arm. He played only a year in the minor leagues.

When he returned, there was no opening for a coach at his alma mater, but there was a job near his hometown. He was hired as both the football and baseball coach at Wake Forest, then located just 22 miles north of Raleigh.

Thompson was not particularly successful as a football coach, compiling a 5-19 record at Wake Forest while State College won a South Atlantic Championship.

It made for some heated matchups when Thompson returned to Riddick Field to face his former school, especially for the Easter Monday games between the two rivals, when every student from both schools, most of the students from Raleigh’s three women’s colleges and every state legislator showed up to kick off both the spring athletic and social calendars for the capital city. When Thompson led Wake to just its second win in the Easter Monday series in 1913, the players carried him around the field on their shoulders, before the game even ended, to the consternation of the crowd.

After three years, Thompson left his positions at Wake Forest to take a job as the secretary and treasurer of the Raleigh Real Estate and Trust Company. It was an unsatisfying position for the trained textiles manager, enthusiastic sportsman and man about town.

So in 1917, at the age of 31, Thompson enlisted in the U.S. Army, training in the ROTC at Fort Oglethorpe, Camp Forrest and Chickamauga Park in Georgia. While there, he contracted the Spanish flu, a deadly virus that circled the planet for two years and killed five times more people than all of the Great War.

Thompson, however, recovered from the disease and was sent back to Fort Oglethorpe to complete his ROTC training, earning an officer’s commission with a rank of first lieutenant on Nov. 8, 1917. Three weeks later, he was called to active duty, just as nearly 2,000 former NC State students, faculty and alumni were during the course of the war.

Thompson was assigned to the 15th Machine Gun Battalion in the 5th Infantry Division at Camp Merritt in New Jersey. His unit shipped out for Europe three days after Thompson’s 32nd birthday. Thompson’s unit was sent to the front lines near Regneville-sur-Meuse to begin the Allied Army’s assault in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel on Sept. 11, 1918. Two days into the fighting and just 30 minutes after he began his first live combat, Thompson was killed in a hail of machine gun fire, the only officer in his division to die during the assault on Saint-Mihiel. He was buried in the American cemetery on the battlefields of France, near Thiaucourt-Regnieville.

Remembering a Fallen Friend

Word quickly spread back home, in the form of a telegram sent to Thompson’s sisters Lillian and Daisy in Raleigh. Living in the town of Hamlet and serving as the president of the Richmond County chapter of the Alumni Association, Sykes found out about his teammate’s death in a small news story in the alumni magazine.

He penned the following letter, dated Oct. 25, 1918, which was published in the magazine’s November edition.

I have just finished reading Alumni News. It was a shock to learn of the death of Frank Thompson. I know Frank did his duty without fear and hit the Hun lines like he did on the athletic field.

I hope that a movement will be put on foot to perpetuate the names of our alumni who have given their lives in France that the world might live in peace. I know that the alumni would subscribe liberally to a fund to be used for this purpose, and it is nothing more than is due our heroes.

With kindest regards to all my College friends,

Vance Sykes (BE 1907)

Soon after, the Alumni Association began a push to build such a memorial. By the next spring, hand-signed checks began to appear on director C.C. “Pop” Taylor’s desk at the General Alumni Office. Five dollars from Alan T. Bowler (1912, BE). Ten dollars from Alvin D. Dupree (BE, 1908). The enormous pledge of $100 from Charles B. Holladay (B.E., 1893), the son of NC A&M president Alexander Quarles Holladay and a member of the inaugural freshman and graduating classes at the school.

“When last on the College grounds, it appeared to me that what greatly needed improvement was a gateway or entrance where Hillsboro Road turns into campus,” Holladay wrote in the letter accompanying his offer. “If plans for this were secured, after allowing first-class artists to compete, I believe the memorial would prove to be a constant reminder of those for whom it was built, and a lasting pleasure to all. If this entranceway is decided upon as a memorial, I shall be glad to contribute $100 for securing competitive plans.”

Sykes himself gave $50, with the following card:

I was pleased to note in the last issue of the Alumni News the interest being taken in the erection of a memorial to our State College men who gave their lives fighting for us on the battle lines of France.

This is a worthy cause, and I feel that every State College man should feel it his privilege to contribute to a memorial to our fallen heroes.

Sykes wanted Thompson’s legacy to live long after the war, in both a physical memorial and a successful athletics program.

At an Oct. 5, 1922, monthly meeting of the Richmond County chapter of the Alumni Association, Sykes and his fellow members voted for a bigger commitment to athletics success at their alma mater, like they had experienced during their careers. They passed a resolution saying “realizing that State College is not keeping abreast with other colleges of its standing in athletics, [we] recommend to the faculty and General Alumni Association that a more progressive athletic policy be pursued, and to this end that a wide-awake, active faculty athletic director, who is fully conversant with all branches of athletics, be appointed. We respectfully ask that Dr. C.C. Taylor be considered for this position.”

They also heartily endorsed the expansion of head coach Harry Hartsell’s staff to include “at least two additional competent coaches.”

Sustained success in football eluded State College until the 1950s, when it became a charter member of the Atlantic Coast Conference. Work on the Belltower didn’t have to wait that long. Construction began in 1921 and was concluded in 1937. The tower was officially dedicated on Nov. 11, 1949.

Shortly after construction of the Belltower began, the NC State Board of Trustees voted to name NC State’s first on-campus gymnasium in memory of its hometown hero, to go along with having his named engraved in the shrine room of the tower along with the other men who died while fighting in or training for the war. Frank Thompson Gymnasium was dedicated on July, 1925. It was converted to Thompson Theatre in 1964 after the opening of Carmichael Gymnasium and renamed Thompson Hall in 2009. Frank Thompson also has a scholarship named in his memory.

Sykes remained active in alumni affairs, as a longtime member of the Memorial Tower Committee, and spent his entire career working for the Sea Board Railway. One of his biggest contributions to the company was designing and building Raleigh’s Boylan Street Bridge.

In 1966, the NC State Alumni Association honored Sykes with the Distinguished Alumnus Award. Throughout the renovation of the Belltower and the construction of Henry Plaza, Sykes’ name has been little noted in the history of the Legend in Stone, a nearly forgotten teammate from more than a century ago. Sykes died in Hamlet on March 12, 1970, at the age of 88 and is buried in Richmond County Memorial Park.

Perhaps that’s fine with the former football lineman and railway division engineer, whose graduation motto in the 1907 Agromeck simply stated: “The truly great are always modest.”

- Categories: