10 North Carolina Sports Legends

Editor’s Note: This is a guest post by North Carolina native Tim Peeler, community relations manager for NC State University Relations – and the unofficial historian of NC State athletics. A former newspaper reporter and sportswriter, Peeler has written three books about NC State basketball and frequently blogs about Wolfpack athletics history. This post is part of our NC Knowledge List series, which taps into NC State’s expertise on all things North Carolina.

North Carolina’s place in the history of athletics is not replete with Super Bowl championships, NBA trophies or World Series titles.

But it does include a Stanley Cup and a slew of groundbreaking pioneers in multiple sports. Memories may have faded through the years, so let’s take a moment to remember some of the most important sports legends (and hidden gems) from the Old North State.

The legend of Jesse Elliott: The most famous sporting story from North Carolina’s earliest days involves horses, forbidden Sunday racing and the appearance of a mysterious stranger who may have been Satan himself. To this day, there is evidence of this deadly encounter about a mile west of Bath, the oldest town in North Carolina.

Jesse Elliott was a hard-drinking, unlikeable young man who claimed to have the fastest stallion in the state, and he took joy in winning clandestine Sunday morning races against out-of-town visitors while his neighbors were at church. One August weekend in 1802, Jesse made plans to race against a new opponent. The plans were made in direct opposition to his wife, who said “I hope you’ll be sent to Hell this very day.”

Jesse Elliott was a hard-drinking, unlikeable young man who claimed to have the fastest stallion in the state, and he took joy in winning clandestine Sunday morning races against out-of-town visitors while his neighbors were at church. One August weekend in 1802, Jesse made plans to race against a new opponent. The plans were made in direct opposition to his wife, who said “I hope you’ll be sent to Hell this very day.”

As spouses do.

Jesse never saw the face of his final opponent, a black-clad newcomer on an all-black horse. At the height of the race, around what is now Beaufort County, the stranger intentionally spooked Elliott’s horse, sending the cocky rider flying into one of the large, ubiquitous pine trees at the mouth of the Pamlico River. Jesse died instantly and the stranger and horse disappeared forever.

Jesse’s minister, who had often preached against the sins of Sunday diversions, had no regretful obsequies, saying hoof prints made by Jesse’s horse were left by “a man on his way to Hell.”

As ministers do.

For more than 215 years, those same bare hoof prints from Elliott’s horse have remained visible to all who care to see them, despite attempts to fill them, grass them over or cover them with pine needles. Read all about it here.

College basketball tournaments: As long as it’s OK to stipulate that the most important event regarding college basketball in the state of North Carolina was the arrival of NC State coach Everett Case, the legendary Indiana high school coach who brought big-time basketball to the state just after World War II, it’s also appropriate to recognize that he was not the first to see the Old North State as a fertile ground for hoops.

There were two significant reasons that Case made the decision to come to Raleigh instead of accepting other head coaching offers. First, at the direction of textile publishing magnate and NC State alumnus Dave Clark, the college began building a large, on-campus arena (now known as Reynolds Coliseum) in 1941, one of the most important structures ever built by the state of North Carolina. It was but a skeleton when Case accepted the job, after its construction was halted during World War II.

There were two significant reasons that Case made the decision to come to Raleigh instead of accepting other head coaching offers. First, at the direction of textile publishing magnate and NC State alumnus Dave Clark, the college began building a large, on-campus arena (now known as Reynolds Coliseum) in 1941, one of the most important structures ever built by the state of North Carolina. It was but a skeleton when Case accepted the job, after its construction was halted during World War II.

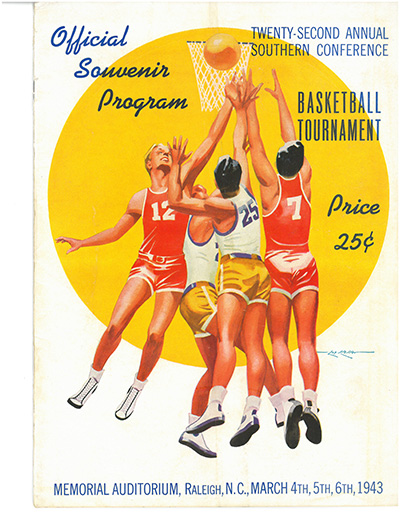

But there was another, underlying reason Case came to Raleigh: As far back as 1933, the state’s capital city was a basketball tournament town. It was in 1933 that eight schools voted to leave the Southern Conference to form the Southeastern Conference, leading the Southern Conference to seek a new home for its popular championship tournament, which had previously been held in Atlanta.

Raleigh had a newly rebuilt municipal auditorium. On the advice of Chamber of Commerce president and future Raleigh mayor Graham H. Andrews, the auditorium had been built with a flat instead of inclined floor, with the thought that it might one day host indoor basketball – a game that was still just a bridge between football and baseball seasons. NC State athletics director R.R. Sermon made the city’s successful bid to host the tournament, and it was organized and run by the Raleigh Junior Chamber of Commerce.

In its 14 years at that site, the league championship event was both popular and a financial success. By the time Case finished his first season, basketball had become popular among the World War II veterans enrolled at area colleges and, even more importantly, their wives. In fact, it had become so popular that games not only filled local gymnasiums such as NC State’s 2,500-seat Thompson Gym, but made Raleigh’s 5,000-seat auditorium obsolete for the Southern Conference – requiring the 1947 tournament be moved to 10,000-seat Duke Indoor Stadium in Durham.

The tournament moved into still larger Reynolds Coliseum in 1951 and was contested there until eight Southern Conference teams left the league to form the Atlantic Coast Conference following the 1953 season. The first 13 ACC tournaments were held at Reynolds, until the league began hosting them at still larger neutral locations, primarily in Charlotte and Greensboro, as North Carolina coaches and players became national legends.

The state has twice hosted the NCAA’s Final Four, in Greensboro in 1974 and in Charlotte in 1994, as well as multiple NCAA and conference events through the years, and has just as much claim to being the birthplace of college basketball superiority as Kentucky or Case’s home state of Indiana.

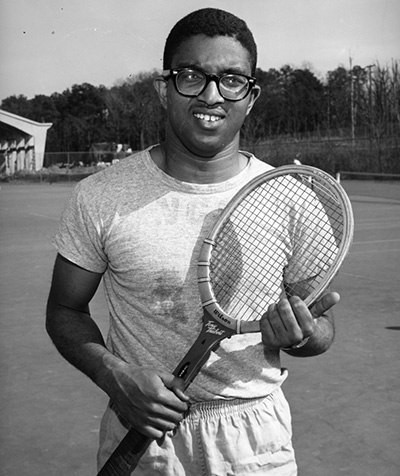

Integrated athletics: On a chilly February morning in 1957 at what is now known as Dorton Arena, NC State freshmen Irwin Holmes and Manuel Crocket, both of Durham, laced up their tennis shoes and competed in the 600-yard run in a freshman track meet against UNC-Chapel Hill, becoming the first black athletes to compete in an ACC-sponsored event.

That fall, Holmes took it a step further by joining the Wolfpack’s varsity tennis team, becoming the league’s first black varsity player in any sport. Though he wasn’t allowed to compete in road matches against conference foes Clemson and South Carolina, Holmes has often hailed his experience at NC State, where he became the school’s first African American graduate when he earned his degree in electrical engineering in the spring of 1960. That year, he was featured in Sports Illustrated’s “Faces in the Crowd” for being the first black athlete voted by his teammates to be co-captain of an ACC varsity program.

And golf lovers may recall that Charlotte’s Charlie Sifford became the first black, full-time member of the PGA Tour in 1961, because of his play at the Greater Greensboro Open.

But it is in basketball especially that North Carolina played a significant role in the integration of college and professional athletics.

From the time John McClendon learned the game of basketball from its inventor, James Naismith, while at the University of Kansas, McLendon brought his fast-paced, high-scoring style of play to the state of North Carolina, including a handful of secret games his teams played against teams from all-white universities.

North Carolina natives Meadowlark Lemon and Curly Neal were pioneers with the barnstorming Harlem Globetrotters, who played integrated games in Reynolds Coliseum as early as 1952. In 1963, Asheville’s Henry Logan enrolled at Western Carolina to become the first black collegiate basketball player at a predominantly white North Carolina college. Throughout the 1960s, Winston-Salem State’s All-American Earl “The Pearl” Monroe and head coach Clarence “Big House” Gaines brought championship basketball to the state, along with other pioneering players from the state’s small colleges such as High Point’s Gene Littles, Gardner-Webb’s Artis Gilmore and Guilford’s World B. Free.

They were all part of the foundation for the ACC’s first two-time African American All-American (North Carolina’s Charlie Scott, 1967-68), its first black ACC Player of the Year (Wake Forest’s Charlie Davis, 1971), the ACC’s first two-time National Player of the Year (NC State’s David Thompson, 1973-74) and perhaps professional basketball’s biggest superstar (UNC’s Michael Jordan).

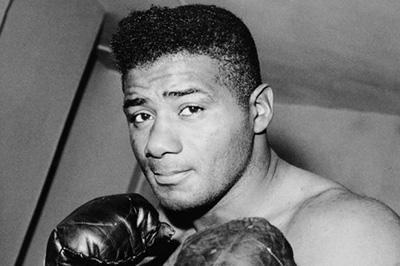

Heavyweight champions Floyd Patterson and James “Bonecrusher” Smith: North Carolina has a significant boxing heritage that includes varsity boxing teams at NC State and other area schools throughout the Great Depression. Significantly, however, two North Carolina natives made huge impacts as professional boxers.

Floyd Patterson was born in the tiny Cleveland County town of Waco, a crossroads community so small that there are four flashing signs that warn about the community’s only yellow light. He was the youngest of 11 children in a family that fled rural North Carolina for New York before Patterson’s fifth birthday. Patterson learned to box to keep himself off the streets of Harlem, and won a gold medal in the middleweight division at the 1952 Olympics. On Nov. 30, 1956, Patterson became the youngest heavyweight champion (21 years, 10 months, 3 weeks and 5 days) in boxing history when he knocked out Archie Moore, becoming the first Olympic gold medalist to win a professional heavyweight title.

Magnolia-born James “Bonecrusher” Smith, besides having the greatest nickname in boxing history, owns a proud distinction: having earned an associate degree from James Sprunt Community College in Kenansville and a degree in business administration from Raleigh’s Shaw University, he is the only college graduate to become professional boxing’s heavyweight champion. Over the course of two bone-battering decades as a professional fighter, Smith earned several championship bouts, finally beating Tim Witherspoon for the heavyweight title on Dec. 12, 1986, before losing it three months later in a unification match against Mike Tyson at Madison Square Garden.

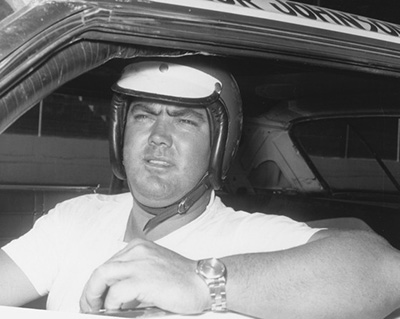

Junior Johnson’s presidential pardon: Pioneers have to endure, and that was certainly the case for bootleggin’ Robert Glen “Junior” Johnson, who helped turn profitable (but illegal) liquor production during the Depression into stock car racing, a loosely organized post-World War II diversion that first gathered in Greensboro and was officially chartered when promoters met in Daytona Beach, Florida, in 1947. It was eventually named North Carolina’s official state sport by the General Assembly in 2011. For years, it’s been one of the state’s biggest economic drivers.

Johnson, however, needed a little help in legitimizing his status as a sporting legend, which he received on Dec. 26, 1985, when President Ronald Reagan gave Johnson a full and unconditional presidential pardon for the driver and racing owner’s 1956 federal moonshining conviction. Johnson had served an 11-month sentence after being caught in a barbed-wire fence while escaping federal revenuers looking for his father’s Wilkes County still.

In 2010, Johnson joined drivers Richard Petty and Dale Earnhardt and NASCAR founders Bill France Sr. and Bill France Jr. in the inaugural class of the NASCAR Hall of Fame, which is located in downtown Charlotte and is maintained by executive director Winston Kelley, an NC State graduate and Concord native.

Read more here about NC State’s participation in the $6 billion car racing industry.

Women’s athletics administrators: Undoubtedly, Gibsonville-native and NC State women’s coach Kay Yow left an indelible impression on college athletics and international competition that would be appropriately included on any list of the state’s most important athletics contributors. Her legacy, however, includes more than coaching teams to Olympic gold medals, winning four ACC championships and waging a courageous fight against cancer.

When Yow was hired by NC State athletics director Willis Casey shortly after the passage of Title IX of the 1972 Education Amendments, she was the coach of three varsity sports and coordinator of women’s athletics. She eventually hired Peace Junior College coach Nora Lynn Finch as an associate coach. When administration became too demanding for a dual role, Casey told the athletics department’s only two female employees that he had a job as women’s basketball coach and a job as coordinator of women’s athletics, and Yow had first choice. Yow chose basketball and went on to win more than 700 games in her 36-year, Hall of Fame career. Finch, meanwhile, spent 31 years at NC State as a pioneering advocate for women’s sports before leaving in 2008 to become the ACC’s senior associate commissioner for women’s basketball, a post she still holds.

They helped pave the way for other successful women in college athletics administration, including Yow’s younger sister, Debbie Yow, who is in her ninth year as NC State’s athletics director, and UNC Charlotte’s Judy Rose, who recently retired after nearly three decades as a successful college administrator, 20 of them as athletics director.

Debbie Yow was one of the nation’s first female athletics directors when she was hired at Saint Louis (1990-94) and the first at an ACC school when she served at Maryland from 1994-2010. Now, she is the longest tenured female athletics director at a Power Five school, but no longer the only woman leader in the ACC, as Pittsburgh’s Heather Lyke and Virginia’s Carla Williams now lead the athletics departments at their schools.

Hockey arrives in the South: Professional hockey did not arrive for the first time in North Carolina when the Hartford Whalers relocated to the Old North State from Connecticut and became the Carolina Hurricanes. It had been here at least 40 years earlier, with minor league teams like the Charlotte Clippers/Checkers, the Greensboro Generals and the Raleigh IceCaps.

When Reynolds Coliseum was first built in the 1940s, it included 12 miles of piping and hardware for a 90-by-200-foot permanent ice rink built by Stahl-Rider Inc. of Raleigh, with a portable hardwood floor laid on top of it for basketball games. The hope was to pay for the operating expenses of the multipurpose facility by opening the arena as the South’s first public skating venue. And for years, Reynolds hosted open skating to the public from 7:30 p.m. until 10:30 p.m. on weeknights, with Saturday afternoon skating also available.

In a nod to the importance of ice sports, Reynolds was officially dedicated on April 22, 1950, prior to the Ice Cycles skating revue. For years it was a week-long host for the Ice Capades and other ice-dancing and skating events (even when Reynolds needed a portable rink after the use of the permanent ice rink was discontinued in the late 1950s when humidity caused by the ice-making equipment began to deteriorate ceiling tiles, causing them to crash to the ground).

On April 18-19, 1952, the Boston Olympics and the New Haven Tomahawks of the Eastern Hockey League played what was billed as the first professional hockey games in the South, with back-to-back contests at Reynolds.

Late in the EHL’s 1956 season, Charlotte became home to the Baltimore Clippers when that team’s arena burned down with 12 contests remaining in the home schedule. On Oct. 27, 1956, the renamed Charlotte Clippers hosted the Johnstown Jets in an EHL regular-season game.

When Charlotte and Greensboro built new arenas in 1955 and 1959, respectively, they both installed ice-making equipment in order to have hockey games in the buildings. In 1958, the Charlotte Clippers played EHL exhibition games against the Philadelphia Ramblers in Reynolds, as Raleigh and Greensboro both toyed with the idea of adding minor league hockey. Public tickets were between $1.50 and $2.50, but students could buy general admission seats for 90 cents.

In 1977, college intramural hockey teams representing NC State, North Carolina, Duke and Wake Forest met in the first Big Four Hockey Tournament, which was the first competitive hockey event held at the refurbished Greensboro Coliseum.

The Whalers relocated to North Carolina following the 1996-97 season, playing their first two seasons in Greensboro before moving into their permanent home, now called PNC Arena, in 1999, where they share the 19,000-seat venue with NC State’s men’s basketball team. With a seventh-game victory over the New Jersey Devils in that building, the Hurricanes won the 2006 Stanley Cup.

Women’s golf pioneer Peggy Kirk Bell: The game of golf had long been established in the Sandhills area of North Carolina when Ohio native Peggy Kirk Bell and her husband, former professional basketball player Bullet Bell, settled at a small lodge in Southern Pines in the summer of 1953.

A founding member of the Ladies Professional Golf Association, she had already spent much of her life playing and advocating for the game through the LPGA, the United States Golf Association and her week-long golf schools, which she called “Golf-aris” and continued until her death in 2015.

She was a constant part of the game’s growth for men and women. In 1996, the USGA brought its U.S. Women’s Open Championship to Bell’s Pine Needles Golf Lodge and Country Club, the first step in connecting its championships to North Carolina’s $2 billion golf economy. It returned again in 2001, 2007 and 2014, while the nearby Pinehurst Country Club built on the women’s success to host the 1999, 2005 and 2014 U.S. Men’s Open.

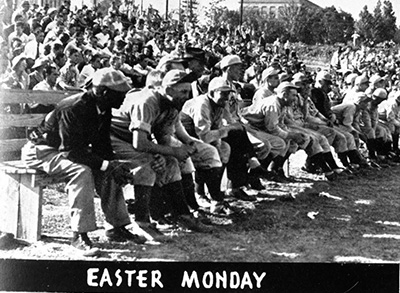

Baseball holiday spectacles: For more than five decades, North Carolina was the only state in the country that celebrated Easter Monday, and baseball is the reason.

The national pastime has always been popular in the state, from the time Babe Ruth hit his first professional home run in Fayetteville in 1914 until today, with 11 thriving minor league teams in Durham, Charlotte, Greensboro, Zebulon, Asheville, Winston-Salem, Kinston, Buies Creek, Hickory, Kannapolis and Burlington.

The national pastime has always been popular in the state, from the time Babe Ruth hit his first professional home run in Fayetteville in 1914 until today, with 11 thriving minor league teams in Durham, Charlotte, Greensboro, Zebulon, Asheville, Winston-Salem, Kinston, Buies Creek, Hickory, Kannapolis and Burlington.

Specifically, the statewide holiday on the day after Easter was created because of the annual game played between NC State and Wake Forest, followed later that night by the PIKA fraternity ball. For a total of 58 years, before Wake Forest College moved from northern Wake County to Winston-Salem, the hotly contested game was a popular getaway for North Carolina lawmakers and students of Raleigh’s three women’s colleges. Those same lawmakers declared Easter Monday an official state holiday in 1935, something that lasted until 1987 when the lawmakers replaced it with Martin Luther King Day on the state calendar.

Perhaps even more unusual were the Raleigh-Durham doubleheaders that were played for years on the Fourth of July and Labor Day. The minor league Raleigh Capitals and the Durham Bulls would play a 10 a.m. game in one town, then drive to the other for an afternoon game.

On July 5, 1915, the two teams started out with a 10 a.m. game at Raleigh’s League Park, then moved to Trinity College’s Hanes Field in Durham. Nothing, however, went as planned. In the first game, the two teams played for 14 innings before Raleigh finally pulled out a 3-2 win, thanks to a run-scoring single by Big Chief Myers. In the afternoon game, the two teams battled until the bottom of the 22nd inning, right up until nightfall. The game ended in a 2-2 tie when the two teams argued about whether Raleigh rightfielder Myers, hero of the first game, caught or dropped a fly ball in the moonlight. With a Durham runner on third base with no outs, the umpire resolved the dispute by calling the game a 2-2 tie.

The two teams continued to play two-town holiday doubleheaders through baseball’s golden age following World War II, but no professional doubleheader in baseball history ever lasted longer than the Bulls-Capitals games in 1915.

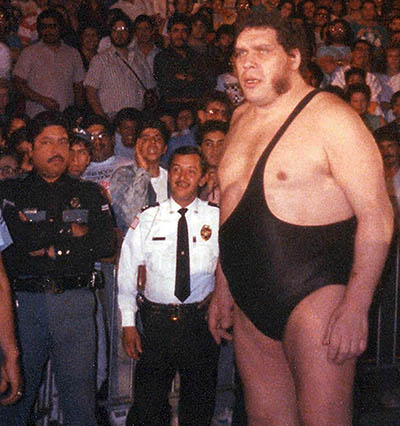

A gigantic getaway: When the aptly nicknamed professional wrestler Andre “The Giant” Roussimoff needed to get away from the constant pressures and struggles of being a 7-foot-4, 500-pound international superstar, he retreated to his 48-acre ranch in Ellerbe, about 90 miles southwest of NC State’s main campus.

A gigantic getaway: When the aptly nicknamed professional wrestler Andre “The Giant” Roussimoff needed to get away from the constant pressures and struggles of being a 7-foot-4, 500-pound international superstar, he retreated to his 48-acre ranch in Ellerbe, about 90 miles southwest of NC State’s main campus.

The Carolinas had long been a wrestling hotbed from the old days of Mid-Atlantic Championship Wrestling at the Charlotte Coliseum, the Greensboro Coliseum, Dorton Arena, the Greenville (South Carolina) Auditorium and high school gymnasiums around both states. It was the precursor for the big-time national operations like the WWE, RAW and WWC.

For the last decade of his life, the French-born Roussimoff tended to his herd of Texas longhorns by tooling around the ranch on his trusty Honda three-wheeler, driving into town to cash his “Princess Bride” royalty checks and hosting larger than life parties with his professional wrestling friends.

His 3,500 square foot, three-story house had an oak tree growing through the roof. Because … of course it did. He once had a beer-drinking showdown with fellow wrestler Ric Flair—whose daughter earned her degree from NC State—in which the two massive personalities reportedly downed 106 12-ounce cans of beer in one sitting.

When Andre died in 1993, his ashes—all 17 pounds of them—were scattered over the Richmond County ranch. Since then, the property has been divided, with parts of it recently going up for public auction.

- Categories: