Researchers Regroup Post Sandy

When Hurricane Sandy whipped through the Mid-Atlantic in October, the superstorm not only damaged hundreds of thousands of homes, displaced thousands of residents and shut down Wall Street, it swept right through the middle of an NC State research project collecting data on insects in New York City. Researchers will return to the storm-ravaged region next month to continue their work.

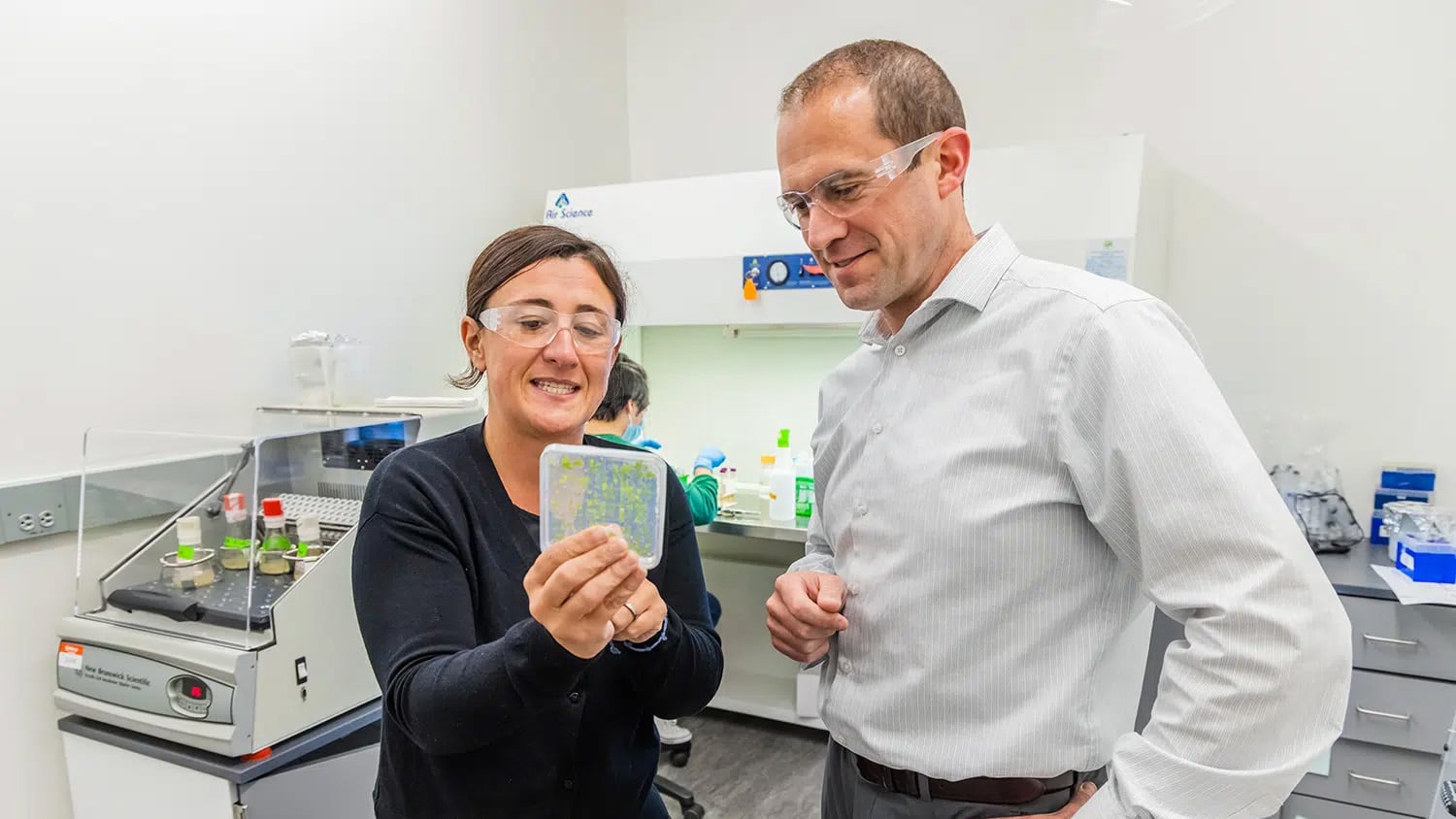

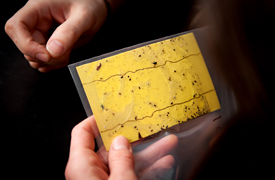

The project got off to a smooth start last summer when ecologists Amy Savage and Elsa Youngsteadt, researchers in the Departments of Entomology and Biology, deposited sticky card traps, data loggers and other measuring devices in trees throughout New York City parks. This was part of Youngsteadt’s research on how urban warming impacts arthropods (such as scale insects, leaf hoppers and caterpillars.) Savage was studying the ecology of Manhattan’s ants.

But in the aftermath of Sandy, thousands of downed trees have been removed by emergency workers cleaning up the mess left by the storm. Also gone are many trees that once housed colonies of insects that were the subject of the research project. Still, there’s plenty to study, the researchers say.

“With the arthropod populations drastically reduced by cleanup we will be able to see the effect large disruptions have on arthropods as well as the amazing contributions these insects make,” Savage explains.

Insects and the City

Retrieving the data will take months. But already the researchers suspect that fewer insects will mean considerably more litter accumulating in New York City parks.

“The waste processing role of arthropods is important. For french fries, corn chips— even paper bags to decompose, arthropods help break garbage down,” Savage says.

The ecologists are also examining how scale insects and other plant-eating arthropods are faring after the storm and expect damaged trees to become more vulnerable to these insects. The end goal is publishing their findings in a scientific journal and understanding better how plants, insects and other organisms all interact to shape the habitat where most humans live.

“Studies show trees help keep cities cooler and lower pollution. Studies also show patients heal more rapidly in the hospital when they can view trees from their window. And yet how trees and insects interact with each other is drastically understudied,” Youngsteadt says.

An Early Love of Insects

These kinds of topics always fascinated both women, even as girls. Youngsteadt grew up in Springfield, Mo. watching her father work as a limnologist, gathering bugs and dirt from lakes. Savage grew up among the mountains of Montana, often inspired by her grandfather, an avid naturalist, to understand the role and impact of plants and insects around her. She loved bugs and it was only when entering college she realized a career in ecology existed.

“Once I learned I could spend my entire life looking at ants if I wanted, I was so excited,” Savage says.

The only drawback to their work is the logistics. Actually accessing their urban experiments is tricky. They must find parking and lug ladders and funnels across parks. Studying ant ecology in New York City means Savage works from medians, setting up baits or studying ants eating discarded food amidst hectic motorists and noisy cars. But both women find their work rewarding.

“Every day I love what I do,” says Savage. “Most of all I love that my work can influence how the world understands things—and that feels great.”

- Categories: