Study Upends Conventional Wisdom, Finds Significant Facial Variation in Pre-Columbian South America

A team of anthropology researchers has found significant differences in facial features between seven different pre-Columbian peoples they evaluated from what is now Peru – disproving a longstanding perception that these groups were physically homogenous. The finding may lead scholars to revisit any hypotheses about human migration patterns that rested on the idea that there was little skeletal variation in pre-Columbian South America.

Skeletal variation is a prominent area of research in New World bioarchaeology, because it can help us understand the origins and migration patterns of various pre-Columbian groups through the Americas.

“However, for a long time, the conventional wisdom was that there was very little variation prior to European contact,” says Ann Ross, a forensic anthropologist at NC State University and co-author of a paper describing the new work. “Our work shows that there was actually significant variation.” The research team also included anthropologists from the University of Oregon and Tulane University.

The recently published findings may affect a lot of hypotheses regarding New World anthropology. For decades, research on pre-Columbian peoples used one sample of 110 individuals to represent the skull variation – including the facial features – of all South American peoples. But that representative sample consisted solely of individuals from the Yauyos people – a civilization that existed in the central Peruvian highlands.

“Our work shows that the Yauyos had facial features that were very different even from other peoples in the same region,” Ross says. “This raises questions about any hypothesis that rests in part on the use of the Yauyos sample as being representative of all South America.”

The researchers evaluated facial measurements of 507 skulls from seven different groups that have been clearly defined by archaeological evidence: the Yauyos, Ancon, Cajamarca, Jahuay, Makatampu, Malabrigo and Pacatnamu peoples. These societies existed at various points between A.D. 1 and A.D. 1470.

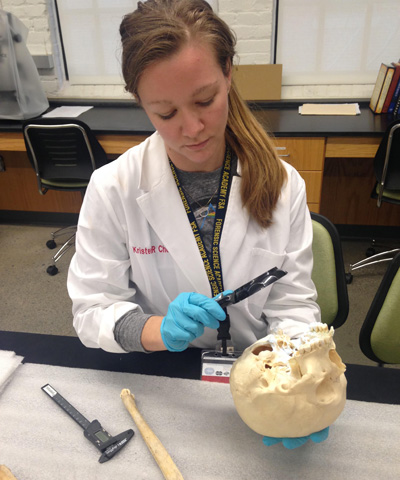

Ross collected facial measurements of the Ancon, Cajamarca and Makatampu remains. John Verano, an anthropologist at Tulane, collected measurements of the Jahuay, Malabrigo and Pacatnamu remains. For the Yauyos, the researchers used measurements made by W.W. Howells in 1973.

The researchers found that each of these groups displayed distinct facial characteristics.

The researchers also plotted the sites where each group’s remains were found. Using this information, they determined that geographical distance was a factor in facial differences between groups.

In other words, the farther apart two groups were, the less they looked alike.

“We’ve now collected samples from across Latin America – and those we’ve already published on can be viewed in a publicly available database,” Ross says. “Our publications so far have focused on variation in specific regions. Next we want to compare variation across Latin America, to see if we can identify patterns that suggest biological relationships, which could be indicative of migration patterns.”

A pre-publication version of the paper on the seven Peruvian groups, “Craniofacial plasticity in ancient Peru,” was made available online by the Journal of Biological and Clinical Anthropology (Anthropologischer Anzeiger).

Lead author of the paper is Jessica Stone, a Ph.D. student at the University of Oregon who did the work while a graduate student at NC State. The paper was co-authored by Ross, Verano and NC State lab technician Kristen Chew.

- Categories: