For Immediate Release

A proof-of-concept study finds that it is possible to identify an individual’s ancestral background based on his or her fingerprint characteristics – a discovery with significant applications for law enforcement and anthropological research.

“This is the first study to look at this issue at this level of detail, and the findings are extremely promising,” says Ann Ross, a professor of anthropology at North Carolina State University and senior author of a paper describing the work. “But more work needs to be done. We need to look at a much larger sample size and evaluate individuals from more diverse ancestral backgrounds.”

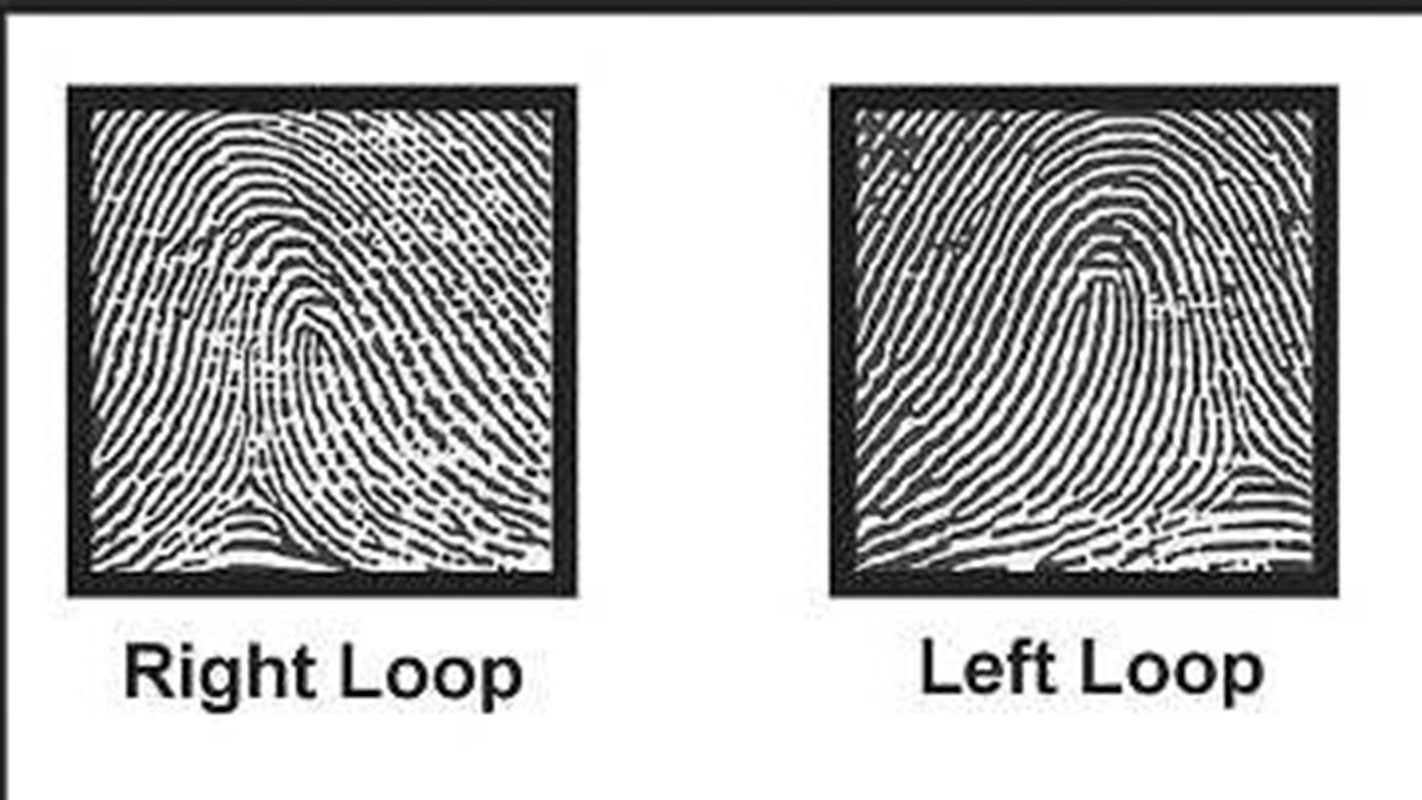

Anthropologists have looked at fingerprints for years, because they are interested in human variation. But this research has looked at Level 1 details, such as pattern types and ridge counts. Forensic fingerprint analysis, which is used in criminal justice contexts, looks at Level 2 details – the more specific variations, such as bifurcations, where a fingerprint ridge splits.

For this study, researchers looked at Level 1 and Level 2 details of right index-finger fingerprints for 243 individuals: 61 African American women; 61 African American men; 61 European American women; and 60 European American men. The fingerprints were analyzed to determine whether there were patterns that were specific to either sex or ancestral background.

The researchers found no significant differences between men and women, but did find significant differences in the Level 2 details of fingerprints between people of European American and African American ancestry.

“A lot of additional work needs to be done, but this holds promise for helping law enforcement,” Ross says. “And it’s particularly important given that, in 2009, the National Academy of Sciences called for more scientific rigor in forensic science – singling out fingerprints in particular as an area that merited additional study.

“This finding also tells us that there’s a level of variation in fingerprints that is of interest to anthropologists, particularly in the area of global population structures – we just need to start looking at the Level 2 fingerprint details,” Ross says.

The paper, “Sex, Ancestral, and Pattern Type Variation of Fingerprint Minutiae: A Forensic Perspective on Anthropological Dermatoglyphics,” is published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Lead author of the paper is Nichole Fournier, a former graduate student at NC State, now at Washington State University. The research was done with the assistance of the City County Bureau of Identification in Raleigh, N.C.

-shipman-

Note to Editors: The study abstract follows.

“Sex, Ancestral, and Pattern Type Variation of Fingerprint Minutiae: A Forensic Perspective on Anthropological Dermatoglyphics”

Authors: Nichole A. Fournier, Washington State University; Ann H. Ross, North Carolina State University

Published: Sept. 23, American Journal of Physical Anthropology

DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.22869

Abstract: Objectives: The majority of anthropological studies on dermatoglyphics examine the heritability and inter-population variation of Level 1 detail (e.g., pattern type, total ridge count), while forensic scientists concentrate on individual uniqueness of Level 2 and 3 detail (e.g., minutiae and pores, respectively) used for positive identification. The present study bridges the gap between researcher–practitioner by examining sex, ancestral, and pattern type variation of Level 2 detail (e.g., minutiae). Materials and Methods: Bifurcations, ending ridges, short ridges, dots, and enclosures on the right index finger of 243 individuals (n = 61 African American

- Categories: