Top History Paper Examines Early Voting Rights Case

It’s a story pulled from today’s headlines: Black voters turn out on election day only to learn that their names have been stricken from the voter rolls. The Republican Party walks a tightrope, struggling to court Southern white conservatives without alienating African-Americans. Democrats worry about losing local elections as the national party shifts left.

But you won’t find this story on Fox News or CNN. This narrative documents events from the 1930s, exhaustively researched and eloquently recounted by an NC State student. And it’s been selected as the best undergraduate history paper of the year in North Carolina.

“I’ve always wanted to study history with the aim of demonstrating how we cannot separate ourselves from our past,” says Micah Khater, the paper’s author, who graduated in May with a degree in history.

She’s done that and more. Drawing on the only surviving transcript of a court proceeding, old newspapers, an 80-year-old diary and numerous archival documents, Khater uncovers a forgotten event in North Carolina history: a rare civil rights victory orchestrated by African-Americans in the Jim Crow era.

The fascinating tale, spun with a historian’s eye for detail and a storyteller’s gift for prose, won this year’s Hugh T. Lefler Award from the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association. The paper, titled “There Will Be Political Dirty Work: Gendered Expressions of Black Resistance in United States v. John Cashion (1936),” is Khater’s senior honors thesis.

Blocked at the Polls

The event that sparked the federal court case at the heart of Khater’s research paper occurred on Oct. 27, 1934, when about a dozen African-Americans attempted to register to vote at precinct No. 1 in Wilkesboro, county seat of rural Wilkes County, North Carolina. The white registrar, John Cashion, jotted down their names on a piece of paper but never transferred them to the registration rolls. To their dismay, none of the black citizens was allowed to vote on election day. They had been disenfranchised — illegally and without warning.

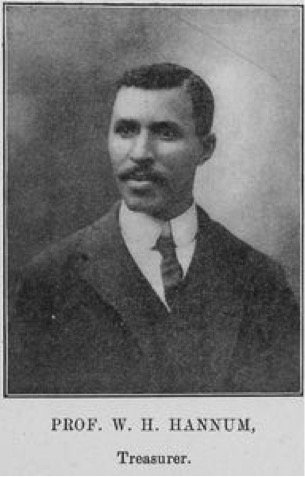

In her paper, Khater tells the stories of three African-Americans who successfully spearheaded a legal challenge against the registrar and testified against him in federal court: schoolteacher Mozelle Cundiff, World War I veteran Claude Petty and college professor William H. Hannum.

While lawsuits asserting civil rights are common today, they were rare — and risky — in the Jim Crow South. But the challengers, backed by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, bravely pursued justice.

Khater is particularly drawn to Cundiff, whose fiery temper masked her natural shyness.

“I feel like I got to know Mozelle in an intimate way,” she says, noting that Cundiff’s daughter gave her access to the teacher’s personal diary, written in 1936. “In many ways she embodied feminist principles, being a strong, educated and independent woman.”

And she was politically active in an era when the activism of women, especially black women, went largely unrecognized. Cundiff’s work to give her students a high-quality liberal arts education was itself a political act. Many whites — even white philanthropists who established African-American schools in the South — sought to restrict blacks to technical trades.

Shifting Politics

Shifting state and national politics factored into the legal battle for voting rights in Wilkes County. The GOP was torn between its need to appeal to white voters and its fear of losing the support of African-Americans, historically committed to the party of Lincoln. Democrats were beginning to attract black and working-class voters, especially in the North, thanks to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s popular New Deal policies. But in the South, the Democratic Party remained firmly in the hands of white supremacists.

Republican-dominated Wilkes County was the ideal place to navigate this complex political terrain and challenge the disenfranchisement of black voters. Petty and Hannum, the two African-American men Khater profiles, were deeply involved in the GOP.

Electoral politics, she explains, offered them a way to assert more than just their political rights.

“Their drive to preserve their influence in Republican state politics demonstrated an assertion of masculinity premised on more recent models of patriotic manhood, namely black men’s participation in the Great War,” Khater writes in her thesis. “Barred from public office and scarred from a war that seemed to give them no advantage, Hannum and Petty sought to confront and challenge the limitations of Jim Crow at every chance.”

It worked, at least in this case. Loath to see his party lose reliable black votes, U.S. District Judge Johnson J. Hayes, a prominent Republican, found the white registrar guilty of unlawful discrimination against black voters in May 1936.

Khater has no illusions that the judge’s ruling was based on anything more than pragmatic political calculus.

“It was a time of crisis for the Republican Party,” she explains. “Republicans knew black voters would vote for them [in Wilkes County], and they didn’t want to lose them. They needed to secure political advantage.”

Still, in the decades before the large-scale boycotts and protests that marked the civil rights movement in the 1950s, it was a rare victory for African-Americans.

Without uncovering and retelling stories like the Wilkes County lawsuit, Khater says, “we lose sight of critical contributions by earlier generations and fail to remember those who fought against racial subjugation in a time when options were limited and risks ran high.”

These stories also give context to today’s civil rights struggles.

Lessons From the Past

“I became really interested in Southern history, particularly African-American history, after taking a class in Southern history my freshman year,” Khater says. “I began to see that I really didn’t understand the context of the society I had spent my whole life in. I grew up in North Carolina, but I didn’t really understand where I lived.”

North Carolina, like much of the South, still has economic and racial disparities rooted in the distant past. Khater finds the parallels between 1934 and 2015 striking.

“I don’t just see echoes of it today; I continue to see institutional white supremacy today,” she says. “Gerrymandering still exists; voter suppression still exists. And that’s hard to stomach.”

Solid Work

Khater’s thesis adviser, history professor Katherine Mellen Charron, praises the breadth and depth of her student’s work.

“Her writing is clear, it’s erudite and it makes a convincing argument about the importance of protecting black voting rights,” she says. “What she has created is a social history rooted in place, as well as a political history that deals with local politics, state politics and national politics. It’s remarkably thorough.”

Charron, a scholar of African-American and women’s history, says the quality of the research — and its recognition by the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association — reflects NC State’s growing excellence in the humanities.

“This is a real honor for Micah,” she says, “and a real honor for NC State.”

- Categories: