An NC State research article about how implementing the Common Core affected North Carolina teachers professionally and personally continues to attract readers, ranking among the top 10 most-downloaded articles in Educational Policy in the year since it was published. We asked co-author Lance Fusarelli, interim head of the Department of Educational Leadership, Policy and Human Development, about the findings and teachers’ experiences. He collaborated with lead author Rachel Porter, who earned a Ph.D. at NC State and serves as executive director of the Centers for Quality Teaching and Learning, and Bonnie Fusarelli, professor and NC State colleague.

1. What was going on when you carried out this study and where are we now with Common Core standards in North Carolina?

The Obama administration, using Race to the Top funds as an incentive, encouraged states to adopt Common Core. This represents a collective effort to standardize what students are learning so states have a uniform level of standards (which they obviously did not as demonstrated in testing via No Child Left Behind). The Council of Chief State School Officers, the National Governors Association, the American Federation of Teachers, and leaders from several states and foundations, with strong support from the Obama administration, were heavily involved in creating the Common Core.

Although 45 states and the District of Columbia have adopted Common Core, opposition such as what is found in North Carolina arises from: (1) objections to a de facto national curriculum and national tests; (2) federal overreach and intrusion into an issue of states’ rights; (3) the fact that Common Core standards may be lower than existing state standards (in at least some states); and (4) the reactions of some students and parents to new, often unfamiliar, ways of learning under the Common Core. Opposition has led some states, such as Massachusetts and North Carolina, to withdraw from Common Core and create new state standards.

2. Why did you choose to look at Common Core from the perspective of individual schools and teachers?

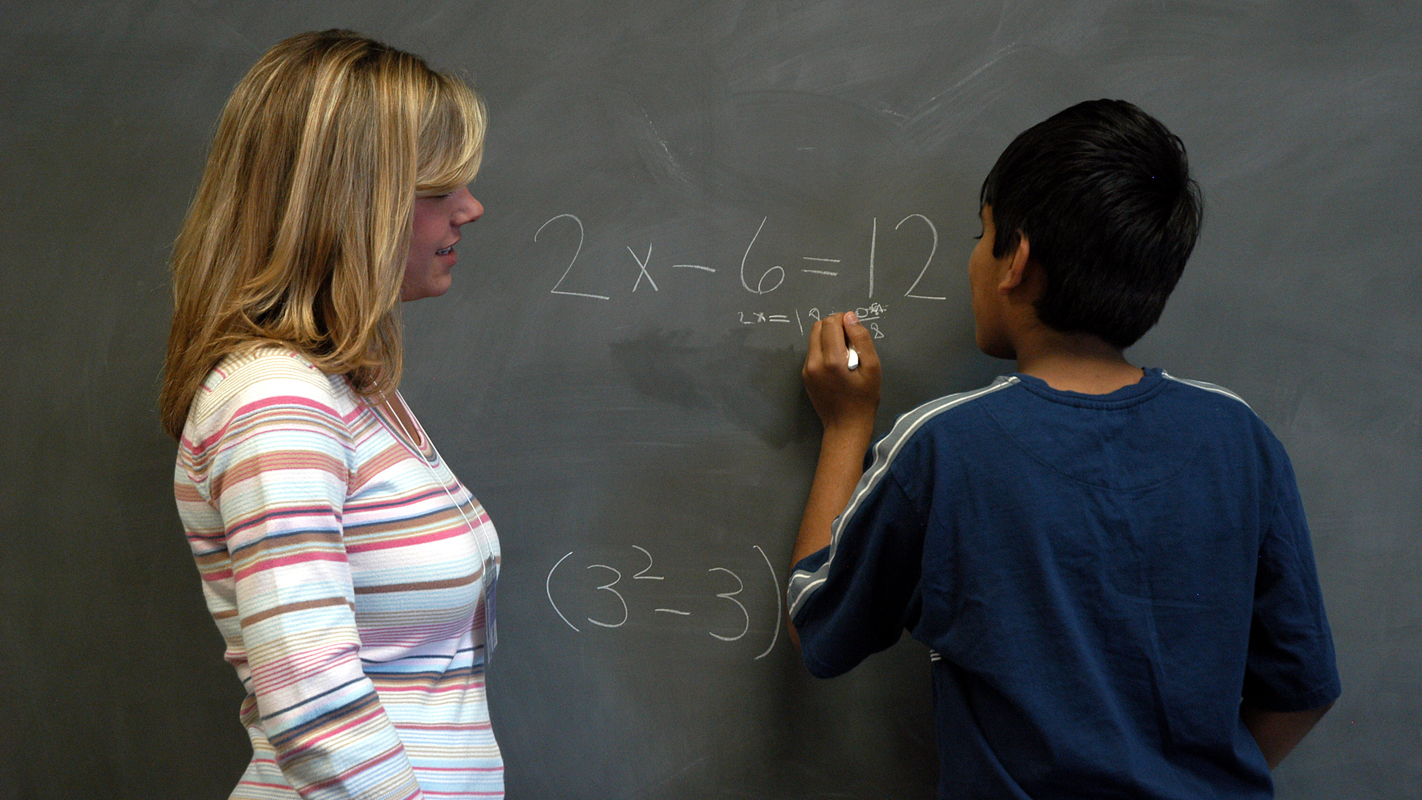

The growing pace of education reforms emanating from the state and federal level is dizzying for educators at the local level, especially those on the front lines—teachers and principals. When you consider how complex schools are, how active state and federal lawmakers are in trying to “fix” education, and how far removed from the classroom many reforms are conceived, it makes sense to study the implementation and impact of reform on the school level, particularly on those most directly responsible for children’s education.

3. What were the major findings from your in-depth case studies at two North Carolina schools?

The lead author of the study, Dr. Rachel Porter, executive director of the Centers for Quality Teaching and Learning, conducted the fieldwork for the study. In many ways, the results are not surprising. Initial implementation of Common Core was uneven across schools. Contextual factors, including differences in communication and training, affected implementation of Common Core across the schools. The amount of change required by teachers was significant. The time teachers had to implement the Common Core was insufficient, which produced a significant level of anxiety and stress for teachers, adversely impacting in the short term both their personal lives and their professional identity.

4. How did teachers describe the process of implementing Common Core?

What surprised us most, although perhaps it shouldn’t have, is how unbelievably stressful implementing the Common Core was on teachers. Teachers described implementation of Common Core as flying the plane as it is being built, as all-consuming. Some felt as if they were drowning in work, with implementation taking time on nights and weekends from their children and families. Veteran teachers said they felt like first-year teachers again, beginning anew, having to recreate the wheel.

Many teachers felt ill-prepared, and we believe this contributed to their stress levels. The teachers wanted to be good teachers, but the new approach challenged them in ways that had them questioning their own competencies.

On the one hand, teachers were given unprecedented freedom to create or use whatever they wanted. On the other hand, in a very compressed time frame, teachers had to create an entirely new curriculum from scratch without the aid of commercially developed curriculum materials and tests, which were still in development. This had profound (often negative) effects on teacher professionalism and identity.

5. Are you surprised at how much interest your article has generated?

A little surprised. The article was nationally one of the top 10 most downloaded articles in October 2015 in the journal Educational Policy. Among researchers, Common Core has generated renewed interest in studying the successes, barriers, obstacles and challenges of implementing major state or federal initiatives at the local level.

It’s a hot topic in North Carolina as legislators appear to be set to replace Common Core with new state standards. North Carolina has only implemented Common Core for three years, so any new change next year will be yet another educational disruption for teachers, forcing them to adapt to yet another new curriculum and to realign testing to that curriculum. It will create more work for teachers. In addition, since North Carolina has already spent millions of dollars and years training teachers to implement the Common Core, replacing it with new, possibly higher, state standards and tests will cost several more million dollars.

- Categories: