Scherr: Renowned Artist, Beloved Teacher

Mary Ann Scherr, a legendary artist and pioneering industrial designer who brought her creative energy and unparalleled skills to NC State, died March 1 at her Raleigh home. She was 94.

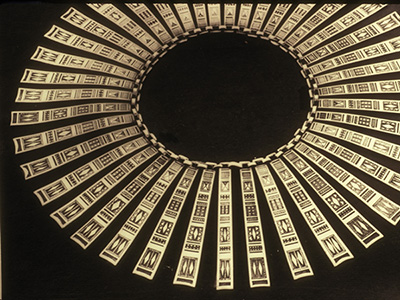

Scherr’s popular classes in jewelry-making at NC State’s Crafts Center often included side trips to her Raleigh home studio, where she guided students through the process of etching complex patterns on bracelets of nickel, bronze and gold.

“If a student had an idea of how to solder something but wasn’t getting it quite right, she would get down and hold their hand and train that hand until it became second nature,” said center director George Thomas. “She was a force for excellence.”

Scherr was a founding member of the Roundabout Art Collective, a group of 25 local artists organized in 2011 by Susan Woodson. The collective operates a gallery in a historic 1920s bungalow on Oberlin Road, just off campus.

She also served on the board of Friends of the Gregg, the membership support organization of NC State’s Gregg Museum of Art & Design.

“The word that always comes to mind when I think about Mary Ann is fearlessness,” said museum director Roger Manley. “She broke through a lot of glass ceilings and broke the mold in a lot of ways.”

Raised in a working class family in Akron, Ohio, Scherr began drawing at the age of 5, using her weekly 3-cent allowance to buy large sheets of paper from a local bakery. Her parents mortgaged their home to pay her tuition at the Cleveland Institute of Art, where she overcame a difficult first semester to earn a scholarship to complete her studies.

In a career spanning seven decades, she would go on to earn acclaim for her work as an illustrator, designer and goldsmith. Her famous clients included Vice President Walter Mondale and the Duke of Windsor — who briefly ruled the United Kingdom as Edward VIII — and her works are housed in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Renwick Gallery and the Vatican Museum of Contemporary Art.

“My soul is in the artwork,” she said in a 2001 interview for the Smithsonian. “My design tools are silence and a free mind.”

Hurray for Hollywood

But before Scherr launched her celebrated career as an artist, she made a detour to Hollywood.

In 1945 a friend from Akron asked her to join him as his dance partner for a six-week tour of nightclubs and theaters on the West Coast. The team, “Duke Alden and Toni,” made a splash with what the Spokane Daily Chronicle called “dance selections and a clever dancing puppet show.”

Six weeks turned into a yearlong gig culminating in a movie contract with Warner Brothers. But before the ink was dry, Scherr had second thoughts.

“At a nightclub in San Francisco, a friend from Ohio was shocked to see me on stage,” she recalled. “He said, ‘You’ve got to get out of this. You’re an artist. You’re not a dancer by training. Get out of here.’ I considered his words, the strange life I had begun to live, and determined that he was right.”

Scherr broke the contract, left Alden and returned to Ohio, where she re-enrolled at the Cleveland Institute of Art — this time majoring in the new field of industrial design.

“One of many decisions that changed my history,” she said.

Postwar World

At the Cleveland Institute Scherr reconnected with Sam Scherr, a high school friend from Akron. The two would graduate, marry and begin their careers in Detroit’s fast-growing postwar automobile industry — Sam at General Motors, Mary Ann at Ford. But they quickly tired of designing hubcaps and hood ornaments and decided to strike out on their own.

Their Akron-based firm, Scherr & McDermott Inc., became one of the leading industrial design firms in the world with offices in Asia and South America.

They designed household products such as the Tappan range and Hoover Suitcase Vacuum, ranked among the Louvre’s 100 best product designs of the 20th century. And they worked with the Agency for International Development’s Alliance for Progress to support emerging design firms in Korea, Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia and Columbia.

Scherr thrived on the variety of the assignments she took on, from illustrating children’s books and game boxes to designing umbrellas, boots and 3-D greeting cards.

“We had so many unique accounts that stretched the imagination, especially in the rubber toy and balloon design category,” she said. “I believe we designed in every direction.”

Working from home after the birth of her son, Scherr designed a line of cookie jars with a nursery rhyme theme for Robinson Ramsbottom Pottery. Years later, after one of the jars featured prominently in a photo of Andy Warhol on the front page of the New York Times (Warhol was an obsessive collector of cookie jars, among other things), their value skyrocketed.

Into Academia

Scherr’s influence as an arts educator cannot be overstated.

She chaired the graduate program in metals in the art department at Kent State University from 1951 to 1978, pioneering the development of high-tech jewelry with health monitoring functions — laying the foundation for a growing industry now supported by multimillion dollar research projects such as NC State’s ASSIST center.

After Scherr and her family moved to New York in 1979, she was tapped to oversee design programs in clay, fiber, metals, wood and glass at the New School for Social Research while also heading the product design department at the institution’s highly competitive art school, Parsons School of Design. Under her guidance, the programs grew to employ 70 instructors serving 800 students.

Despite a school schedule that seemed like an “eight-day-plus week,” Scherr continued to work as an artist and designer in her home studio, first in the family’s brownstone on 85th Street and York Avenue, later in a remodeled 5,000-square-foot loft in SoHo on Broadway.

Among her most successful projects was a line of anodized titanium jewelry that she introduced at the International Boutique Festival in 1982. Orders came in so fast, she hired five designers to produce more than 200 pieces a day.

“I worked the chair position at Parsons by day, and designed titanium jewelry at night,” she said. Demand dwindled after counterfeiters flooded the market with cheap knockoffs of Scherr-designed bracelets, necklaces and earrings.

Still, Scherr had plenty to keep her busy.

She was commissioned by Alcoa, the Aluminum Company of America, to sculpt four wax mythological figures for their promotional magazines; and by U.S. Steel to design and fabricate a collection of jewelry to illustrate the beauty and durability of their metal.

“My background reads like a telephone book,” she said. “Because once the work became too familiar, I had to move on and on.”

Her final move, in 1989, brought Scherr to Raleigh, where she taught at Duke, Meredith and NC State, and where she continued to pioneer new techniques, work with new materials and inspire a new generation of artists.

Scherr was predeceased by her husband, who died in 2002. She is survived by her daughter, Sydney, and sons Randy and Scott.

Memorial contributions may be made to the Gregg Museum of Art and Design. Checks should be made payable to NCSU Foundation with “Gregg Enhancement Fund (for Mary Ann Scherr)” on the memo line.

Please mail checks to:

Mona Fitzpatrick, Program Associate

Arts NC State

Campus Box 7306

Raleigh, NC 27695-7306

Call 919-515-6160 for more information.

- Categories: