Getting in Touch with the Designer in All of Us

Editor’s Note: This is a guest post by Megan Skrip, science communicator with NC State’s Center for Geospatial Analytics in the College of Natural Resources.

Payam Tabrizian is a landscape architect and Ph.D. student in design, but he firmly believes that designing landscapes shouldn’t be limited to the professionals. “All people are designers by nature,” he says, “and they should be designers”– they need only the chance to shine. At the Center for Geospatial Analytics, Payam keeps this motto in mind as he develops high-tech tools that bridge real and virtual worlds. His research also bridges disciplinary gaps between design and the geospatial and cognitive sciences. His central aim, he explains, is “to unleash people’s creativity.”

Now, he and his colleagues Anna Petrasova and Brendan Harmon are one step closer to liberating the imaginations of professional and amateur designers alike, as they bring landscape design into the fast lane and make it something you can literally put your hands on.

Traditionally, professional landscape design plans take months to develop. From the original concept sketch to final approval, these plans require a range of software expertise to produce, and they pass through the hands of many people who have the skillsets to help visualize and interpret the initial ideas, as well as assess how the landscape might function ecologically. Thanks to Payam and his colleagues, now the entire process of hand-sketching, three-dimensional modeling, and assessing landscape pattern takes just minutes, and anyone can do it.

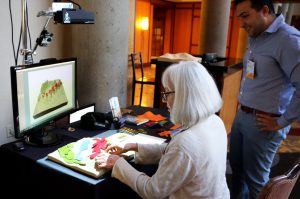

Their solution is a high-tech but intuitive one: a person simply arranges cloth pieces on the surface of a landscape model to represent different vegetation types, and as that arrangement is scanned and fed into a computer, the user receives immediate feedback about ecological indices, such as landscape complexity and biodiversity, and can see their creation rendered as a photorealistic 3-D model in a virtual reality display. What used to take months can now take minutes, and designers can refine their plans over and over in response to the near-real-time feedback.

Payam’s approach uses the Center for Geospatial Analytics’ celebrated Tangible Landscape system, developed by professor Helena Mitasova, associate director of geospatial visualization, and her Ph.D. students, Anna Petrasova, Vaclav Petras, and Brendan Harmon. Tangible Landscape runs on open source GRASS GIS software coupled with a scanner and projector; Payam has connected the system with the open source 3-D modeling and rendering software Blender, enabling traditional bird’s-eye views of landscapes to be visualized at ground-level, from the human perspective, in virtual reality.

Any person regardless of their expertise can sit down with a Tangible Landscape setup, equipped with a set of colorful cloth pieces, and arrange those pieces to design a landscape from scratch. And Payam believes it’s important that they do. Everyone has a sense of beauty, balance, and composition, he explains, and all they need to design landscapes are the tools that can help bring their visions to life and help them understand what their designs mean for the surrounding ecosystem.

The new technology produces a dynamic dashboard that reports the size, shape, number, and diversity of vegetation patches the designer chooses—variables important to consider from an ecological perspective. “This idea of landscape metrics is intimidating for landscape ecologists, let alone designers,” Payam says, but the dashboard breaks down barriers for considering how designed landscapes could affect biodiversity, habitat suitability, and ecosystem function.

Payam and his collaborators unveiled the new technology at the April 2017 annual meeting of the US regional association of the International Association for Landscape Ecology (US-IALE) in Baltimore, MD. One of the many users of the demo was Joan Iverson Nassauer from the University of Michigan, co-editor-in-chief of Landscape & Urban Planning and a distinguished scholar in the fields of landscape architecture and landscape ecology. “It was great fun to use this technology,” she told Payam by email after the conference, “and the results of each trial could be very informative for designers.”

So, what’s next? Payam and his team will soon invite faculty from NC State’s Department of Landscape Architecture to experiment with the prototype and offer their feedback. Equipped with tracing paper, markers, and a variety of colored felt pieces, these faculty will have the enviable task of designing landscapes in a way that is both fast and fun, and which brings them immediately into the places they create. Perhaps soon, all of our inner designers will be able to do the same.

- Categories: