New Early Human Specimens From the Rising Star Cave System: Q&A With Chris Walker

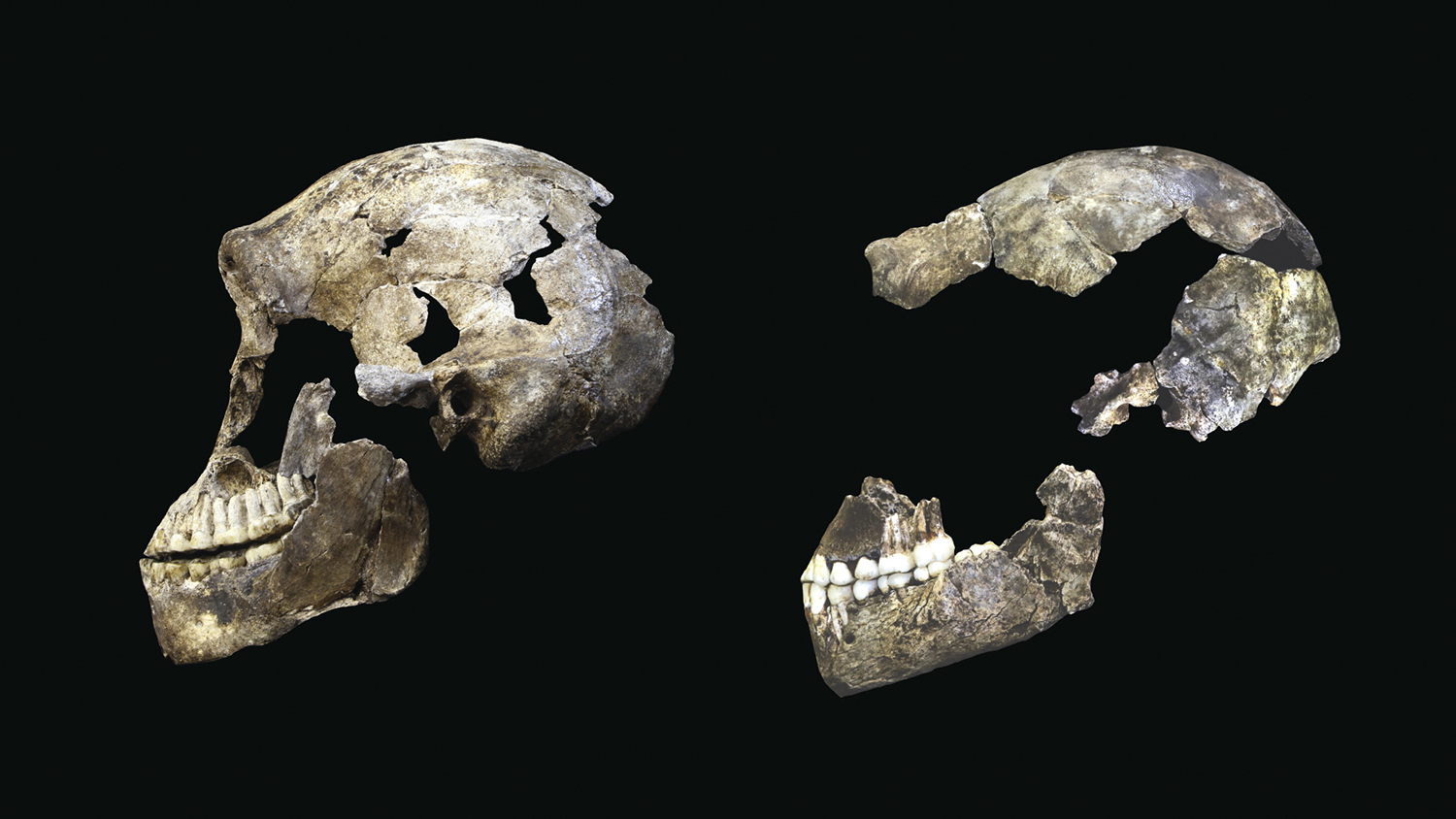

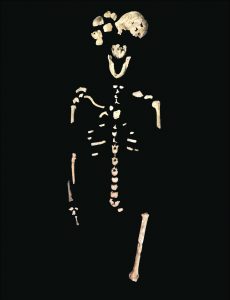

In 2013, anthropologists discovered the fossilized remains of at least 15 hominins, or extinct human relatives, within the Dinaledi chamber of the Rising Star cave system in Gauteng Province, South Africa. The remains were determined to be from an entirely new hominin species, dubbed Homo naledi by the researchers. In November of that year, more specimens were found within another chamber – the Lesedi chamber – of the same cave system. In their latest findings, the authors confirm that these fossils are also H. naledi, and that the species may have existed more recently than their anatomy suggests.

The discovery of H. naledi – and the unique placement of these fossils – raised many questions about this new human ancestor and its place in the human family tree. When did they live? What did they look like? And was it possible that they deliberately disposed of their dead?

Chris Walker is an assistant professor of anatomy at NC State, a co-author of the research, and has examined the H. naledi fossils first-hand. In this Q&A, he shares information about the discovery and what it means for our understanding of ancient early humans.

THE ABSTRACT: What was your role in looking at these fossils?

WALKER: One of my specialties is hind limb anatomy. So my role on the research team investigating these fossils has largely focused on that anatomical region, with particular attention to the femur (thigh bone) and tibia (shin bone). Sixty H. naledi fossils (from a total fossil collection numbering 1550), representing one of those two bones, were recovered from the Dinaledi chamber of the Rising Star cave system. In the Lesedi chamber, of the 131 fossils found, only three were from the hind limb and all three were femurs. Nevertheless, these three femur fossils are important new pieces in the puzzle of understanding H. naledi. The Lesedi femurs provide a more complete picture of thigh anatomy in the species, meaning we can now more effectively study how individuals of the species walked, how tall they were, how much they weighed, and how they differed from one another. My role with the new fossils was to lead the analysis of these thigh bones.

THE ABSTRACT: How did researchers determine that these fossils belonged to an entirely new species?

WALKER: Each fossil was compared to other examples of the same bone in the hominin fossil record both qualitatively and quantitatively. Some H. naledi fossils are anatomically similar to fossils attributed to other species while some features found in the H. naledi fossils are seen nowhere else. Ultimately, it was the anatomical mosaic of the fossil assemblage as a whole, along with a handful of unique traits, that led us to conclude that the Dinaledi (and Lesedi) fossils belong to a new species (H. naledi). If we found just the arm or just the foot, for instance, we probably wouldn’t have assigned the fossils to a new species, but the combination of all of the bones, all of the preserved anatomy, is unlike any previously known species.

THE ABSTRACT: How old are these specimens? Did they live at the same time as Neandertals or Homo sapiens?

WALKER: The Lesedi fossils have not yet been dated, but the fossils from the Dinaledi chamber appear to be between 236,000-335,000 years old. This is surprisingly young for a species that, while assigned to the same genus as us (Homo), is still very primitive with respect to a number of features, such as a brain not much larger than that of a chimpanzee and a trunk and arms that resemble an ape’s. This time range roughly coincides with the earliest evidence of humans (H. sapiens) in Africa. Neandertals were certainly alive around the same time as H. naledi from Dinaledi, but, based on current evidence, they were geographically isolated from each other, with Neandertals being primarily located in Europe and western Asia. The possible ancestor to both humans and Neandertals, H. heidelbergensis (found in Europe and Africa) is, perhaps, the mostly likely of known hominin species to have overlapped with H. naledi in both time and space. There are also some hominin fossils found in southern Africa dated to around the time as H. naledi from Dinaledi which are taxonomically uncertain (meaning, scientists aren’t really sure which species they belong to). So, in summary, H. naledi probably interacted in some way with other human relatives and there’s a chance that members of the species even encountered early individuals of our own species.

THE ABSTRACT: Did H. naledi bury their dead?

WALKER: Unfortunately, the answer to this question is unresolved. There is currently no direct evidence that H. naledi deliberately disposed of their dead; however, the researchers studying the cave geology and deposition of the fossils have failed to disprove the deliberate disposal hypothesis. There is evidence contradicting all other hypotheses tested, such as that the bodies washed into the chamber from somewhere else or that the bodies were brought deep into the cave by a carnivore. So, while the deliberate disposal hypothesis fits the unique circumstances surrounding the Dinaledi fossil assemblage quite well, it remains untested and is, perhaps, untestable with current evidence. We know that some early humans buried their dead (often with symbolic artifacts). We know that the same is true for Neandertals. H. naledi lived around the same time as these groups, so, they weren’t that far temporally removed from evidence of burial behaviors in other species, but it will take something concrete to ultimately solve the mystery of how these hominins ended up in remote parts of a complex cave system, mostly by themselves.

For more information about the latest find, check out these papers, published in eLife:

‘New Opportunities Rising’ (an Insight article accompanying all three research articles)

All contents, including text, figures and data, are free to reuse under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Categories: