Editor’s Note: This is a guest post by Walt Wolfram, William C. Friday Distinguished University Professor of Linguistics at NC State. This post is part of our NC Knowledge List series, which taps into NC State’s expertise on all things North Carolina.

The Linguistic Landscape of North Carolina

As North Carolinians celebrate the many material and cultural resources of the state, we sometimes overlook one of its most noteworthy legacies: its unique dialect and language traditions. No state has a more diverse – or beguiling – dialect landscape.

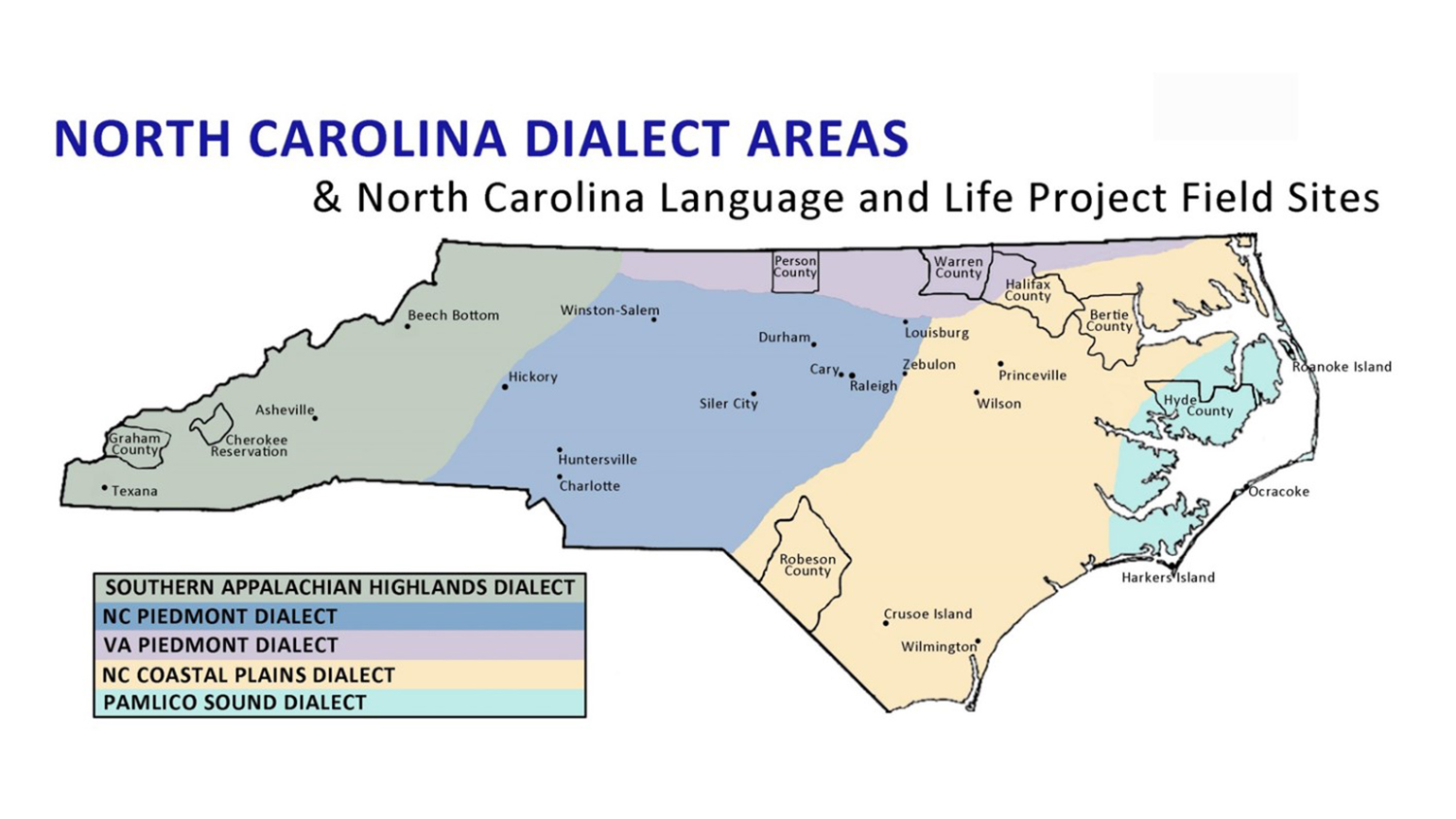

Over the past quarter of a century, the Language and Life Project at North Carolina State University has attempted to capture the language tradition of the Old North State by conducting more than 3,500 interviews with residents from Murphy to Manteo (literally!). In the process, North Carolina has become the most linguistically documented state in America, and all of the recordings are preserved in an online archive.

But we have also tried to share our knowledge with North Carolinians through an array of public and educational venues: documentaries (e.g., Voices of North Carolina, Mountain Talk, The Carolina Brogue), permanent and limited-time exhibits (e.g. Ocracoke Preservation Society, Museum of the Southeast American Indian, North Carolina State Fair), popular books (e.g. Talkin’ Tar Heel, Hoi Toide on the Outer Banks, Fine in the World: Lumbee Language in Time and Place), and a curriculum on language diversity for Grade 8 Social Studies (called “Voices of North Carolina: From the Atlantic to Appalachia”) endorsed by the N.C. Department of Instruction. Through these public outlets and activities, North Carolina has now become the most linguistically celebrated state in the U.S.

To give a sense of the dialect landscape of the Tar Heel State, I have selected a half-dozen dialect expressions that tell complementary stories of our state’s unique language tradition. At the same time, they also convey a sense of how dialects dynamically transmit the rich history and culture of our state.

North Cackalacky (North Carolina):

The Old North State has endured lots of nicknames over the centuries, but one of the most revealing is the term North Cackalacky. Ironically, the term Cackalacky speaks to an unwitting conspiracy of outsiders, insiders, the sweet potato industry, and the barbecue-sauce industry to highlight the significance of native status. Intriguing etymologies – or accounts of how the word was developed – have been proposed:for example, the Cherokee term tsalaki, meaning ‘Cherokee’, pronounced “cha-lak-ee”; the German word for cockroach, kakerlake; and the Scottish soup cocklakeelie. But the most probable origin is that it developed from a kind of sound-play utterance once used to parody the rural ways of people from Carolina.

The Old North State has endured lots of nicknames over the centuries, but one of the most revealing is the term North Cackalacky. Ironically, the term Cackalacky speaks to an unwitting conspiracy of outsiders, insiders, the sweet potato industry, and the barbecue-sauce industry to highlight the significance of native status. Intriguing etymologies – or accounts of how the word was developed – have been proposed:for example, the Cherokee term tsalaki, meaning ‘Cherokee’, pronounced “cha-lak-ee”; the German word for cockroach, kakerlake; and the Scottish soup cocklakeelie. But the most probable origin is that it developed from a kind of sound-play utterance once used to parody the rural ways of people from Carolina.

In the 1940s, “Cackalacky” was used in a somewhat derogatory way by outsiders. For example, servicemen assigned to rural bases in the state in the 1940s referred to their environs as “Cackalacky,” deriding the rural ways of native North Carolinians. Though it may have been intended as an insult, over time the term was reappropriated by natives, and it is now embraced affectionately as a positive reference to state identity. The term has even been appropriated by commercial products that wish to reflect their downhome, regional heritage – the original Cackalacky Spice Sauce, a zesty, sweet potato-based sauce, was trademarked in 2001 and is now distributed throughout the state and well beyond. The positive use of North Cackalacky is spreading, and the pin-back button that reads “I speak North Cackalacky” is one of the most popular items given away at our annual exhibit on languages and dialects at the North Carolina State Fair in Raleigh.

Dingbatter (tourist):

In the early 1970s, the Outer Banks of North Carolina got access to television broadcasts. At the time, the most popular sitcom was All in the Family, a controversial program that parodied a misogynist and racist character, Archie Bunker (played by Carroll O’Connor), who referred to his wife Edith (Jean Stapleton) as a “dingbat” for her alleged lack of common sense.

In the early 1970s, the Outer Banks of North Carolina got access to television broadcasts. At the time, the most popular sitcom was All in the Family, a controversial program that parodied a misogynist and racist character, Archie Bunker (played by Carroll O’Connor), who referred to his wife Edith (Jean Stapleton) as a “dingbat” for her alleged lack of common sense.

At the time, outsiders on Ocracoke and other Outer Banks islands were referred to as foreigners or strangers, but the term dingbatter seemed like a perfect way to describe the lack of common sense sometimes exhibited by tourists who tangle their fishing lines with commercial fishers and think the middle of Highway 12 is a walking trail. To this day, outsiders on Ocracoke are referred to as dingbatters, though it is losing some ground to the blended term touron, a combination of tourist and moron. This kind of appropriation demonstrates two important lessons about language variation. First, it illustrates how local regions readily adopt terms that separate insiders and outsiders, whether it’s dingbatter on the Outer Banks or Jasper and peckerwood in the mountains of North Carolina. And it reveals how dynamic and creative words can be, as local communities ascribe labels to insiders and outsiders.

Boot (trunk of a car):

One of the well-known differences between British English and American English is the different terms for the primary storage area of a car. In America, it’s called a trunk and in England it’s a boot. Travelers to the Coastal Plain of North Carolina, however, may be surprised to find that rural residents in these areas also refer to it as a boot. From counties such as Bertie and Martin in the northern Coastal Plain to Brunswick and New Hanover in the south, older residents may use the term boot to refer to what most Americans call a trunk. The residents did not travel to England to pick up the term; it’s simply an older form in English that was used to refer to the luggage compartment that often sat under the seat by the boots of the driver in horse-and-buggy times. Given the history of small, isolated rural communities in North Carolina, it stands to reason that it is a state that retains is fair share of “relic” dialect terms.

Sigogglin’ (crooked, not straight):

Words that describe attributes of objects or moods of people (e.g. ill for ‘angry,’ jubious for ‘afraid’ or ‘hesitant,’ mommuck for ‘harass’ or ‘bother’) are often vulnerable to dialect differentiation, so it stands to reason that an adjective that describes something that “just ain’t quite straight” or is “off from the perpendicular” would be an ideal dialect marker.

Words that describe attributes of objects or moods of people (e.g. ill for ‘angry,’ jubious for ‘afraid’ or ‘hesitant,’ mommuck for ‘harass’ or ‘bother’) are often vulnerable to dialect differentiation, so it stands to reason that an adjective that describes something that “just ain’t quite straight” or is “off from the perpendicular” would be an ideal dialect marker.

In the Smoky Mountains, sigogglin’ (pronounced ‘sigh-gog-lin) is the unique term of choice. But on the coast of North Carolina, cattywampus and whopperjawed are favored. The term wampus cat, derived from cattywampus, may be used on the coast to describe a person who might be “a little off.” Colorful descriptive terms like these characterize the dialects of North Carolina.

Weren’t (was not):

It might seem strange to include a verb form like weren’t in a list of distinctive North Carolinian dialect expressions, but it illustrates an important point about dialects – that they are not random deviations from mainstream dialects. Instead, they have highly intricate patterns or rules that govern their usage.

The use of weren’t where other dialects use wasn’t (as in “I weren’t there” or “It weren’t in the house”) is only found among American English dialects in the mid-Atlantic coastal region. In North Carolina, it is used on islands such as Ocracoke, Harkers Island, and other historically isolated coastal communities, but it is also found among the Lumbee Indians in mainland Robeson County, where the community has been culturally isolated.

This patterning of weren’t reflects a peculiar, structured reorganization where was is ONLY used in positive or affirmative sentences, and were is ONLY with negative sentences. Positive sentences would look like this: I was there, You was there or (S)he was there. All negative sentences would take the form weren’t: I weren’t there, You weren’t there or (S)he weren’t there. The alignment of was with positive sentences and were with negative sentences is quite different from the majority of English dialects, where was is used with singular forms (I was, he was, etc.) and were is used with plural forms (we were, they were, etc.). This distinctive grammatical trait is characteristic of a number of regional and social dialects in England as well (e.g. Fens, East Anglia) but in the U.S., it is peculiar to a few geographically or culturally isolated regions.

Might Could (may or might be able to):

The expression might could is hardly unique to the Tar Heel State. It is as widespread and Southern as kudzu! But in North Carolina, it is so common that it is barely noticeable – unless you are a Yankee transplant.

The expression might could is hardly unique to the Tar Heel State. It is as widespread and Southern as kudzu! But in North Carolina, it is so common that it is barely noticeable – unless you are a Yankee transplant.

Its use by North Carolinians is unique because it is no respecter of social class in North Carolina; in fact, the last five governors of the state routinely used the term without fear of linguistic censure. So-called “double modals” are combinations of two verbs expressing moods, such as certainty, possibility, obligation or permission. Sentences such as “I might could go there” or “You might oughta take it” serve a special intentional purpose, lessening the force of the obligation conveyed by a single modal. A sentence like “She might could do it” is less forceful than single modals such as “She may do it” or “She can do it.” So a person who responds to an invitation to come to a party with “I might could come” is not obligated to attend. They may or may not show up, but don’t be disappointed if you don’t see them. We can see how this mitigated obligation might come in handy for a politician – or any other North Carolinian. In fact, these kinds of expressions may give insight into the cultural notion of “Southern politeness,” along with Bless your heart, a superficial compliment to camouflage an underlying insult.

- Categories: