Creature Care: Veterinary Medicine at the N.C. Zoo

NC State graduate Jb Minter cares for more than 400 species of animals at the world's largest natural-habitat zoo.

On this most typical of atypical days, Jb Minter is deeply involved with one of his favorite animals — Olivia, the African southern white rhino.

As the director of animal health at the North Carolina Zoo in Asheboro, the 2008 graduate of NC State’s College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) is responsible for the well-being of more than 400 species of animals, from 4-ounce tree frogs to 6-ton elephants to middle-aged rhinos like Olivia.

A Day in the Life of a Zoo Vet

On this day, his rounds take him from Africa to North America, the two continents represented on the 2,600-acre park, the world’s largest natural-habitat zoo. He’s not only checking on Olivia, but also 1-year-old baby Nandi at their behind-the-scenes inspection enclosure behind the wide-open African plain.

There’s always something to do around the park, which Minter roams in an extended-cab pickup truck.

He’s checking out the feet and eyes of C’sar, the African bull elephant who had cataract-removal surgery in 2011 and ’12 by NC State assistant professor of ophthalmology Richard McMullan. With limited sight, the 45-year-old giant’s surgically repaired eyesight needs constant monitoring.

There really isn’t a typical day at the zoo, and that’s the best part of this job.

Next, Minter looks over Mimoso, a critically endangered eastern mountain bongo, a so-called “bleeding antelope” because of the red oil it secretes onto its chestnut-colored coat, to make sure she is, in fact, not bleeding. It’s one of only about 100 remaining in the world.

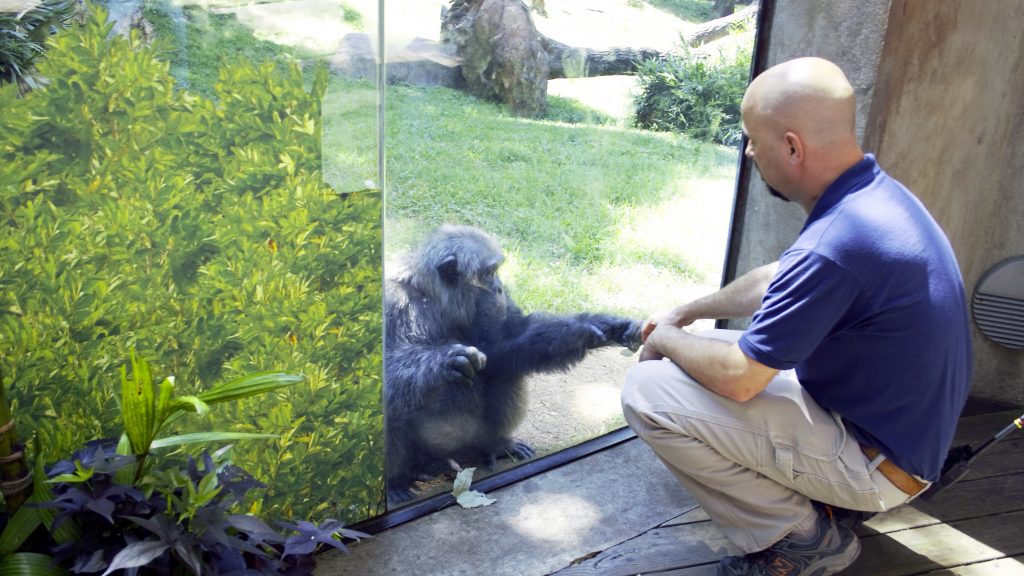

Accompanied by a handful of the zoo’s 70 or so animal caretakers, Minter does a visual inspection of an NC State-red scarlet ibis at the enclosed R.J. Reynolds Aviary, stops by the chimpanzee habitat to fist bump Jon though the glass and checks out the healing of Inca, a short-tempered ocelot.

All before lunch.

“There really isn’t a typical day at the zoo, and that is the best part about this job,” Minter says. “Every day is different.”

Minter’s job certainly ranks near the top of the coolest in the state, right up there with Cape Hatteras lighthouse keeper, statewide elevator inspector and Howling Cow taste-tester. He makes it even more fun by stopping every now and then to engage with and educate a puzzled visitor or a lost family struggling to push a stroller up one of the many hills at the base of the rolling Uwharrie Mountains.

An Office Like No Other

With more than 830,000 visitors in 2018, the state-operated and funded zoo ranks as North Carolina’s third most popular tourist attraction, behind the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh and Fort Fisher State Historic Site in Kure Beach.

It maintains strong ties to NC State’s College of Veterinary Medicine, not only in the treatment and care of the animals, but as a teaching laboratory for students interested in large and exotic animal care. Every year, the zoo hosts numerous CVM students as well as playing an integral role in the teaching of zoological medicine residents.

The zoo got its start in August 1967 at NC State’s newly opened Carter Stadium. That’s where the Raleigh Jaycees hosted a fundraising NFL exhibition game between the Washington Redskins and New York Giants, which generated $18,000 to fund a feasibility study for creating a statewide zoo. The Jaycees hosted similar games the next three seasons that benefited the zoo effort.

In the four-and-a-half decades since the zoo opened with great fanfare on Aug. 2, 1974, the animals have never been out of the hands of an NC State-affiliated veterinarian, since both initial caretaker Jim Wright and Mike Loomis, the zoo’s first full-time vet, held adjunct positions at NC State.

Becoming an Elephant Doctor

Minter, a native of Virginia Beach, Virginia, began the journey to his position with an animal science degree from Virginia Tech and a DVM degree at NC State. After a large-animal internship at Illinois, he worked at a small-animal practice in Florida.

“I had some experience working with domestic animals and with cattle and horses,” Minter says. “And those are the things they teach you in vet school. They want you to be able to deal with horses and cows and pigs and goats and cats and dogs.

“You might do a little bit with birds and some smaller exotics, but you don’t really get experience with the really big exotics.”

So he returned to NC State to begin a highly competitive three-year residency to complete his board certification in zoological medicine. Following his residency, he did a stint at the Great Plains Zoo in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

From hissing cockroaches to dart frogs to large pachyderms, Minter has handled just about every kind of animal since he returned to the NC Zoo in 2014, about a year before Loomis announced his retirement. Minter was then elevated to director of animal health, overseeing the staff of the veterinary division.

“We oversee the health of the entire collection of animals,” Minter says. “That’s our main mission. But in conjunction with that, I also am an educator so I work with guests that are coming to the park to teach them about the animals. I’m also an educator at CVM, teaching veterinary students there. We have students who come here as well.”

As one of about 215 board-certified zoo veterinarians in the U.S., Minter is joined by other NC State CVM graduates or residency program alumni in similar jobs at the North Carolina Aquariums, the San Diego Zoological Park, the National Zoo in Washington and the London Zoo. He maintains close ties to the specialists at CVM. Just a few weeks ago, the zoo sent a porcupine to Raleigh for an MRI.

Minter’s work has also taken him to the home of his favorite exotic animals: central and west Africa. He has worked with Loomis in the placement of satellite radio telemetry collars to track forest elephant herds.

“They are using that information to help mitigate human-animal conflict,” Minter says. “A herd of elephants can wipe out a year’s worth of crops in a single night. We can use the collaring to warn the villagers so they can get the elephants away from their crops before they are destroyed and without harming the animals.”

For Minter, it’s just another way he uses his NC State training to educate, sustain and improve the relationships between people and animals.

- Categories: