Major Player

Billy Ray Vickers learned the value of hard work growing up on a farm in the Blue Ridge foothills. The lessons he learned on and off the football field at NC State propelled him to a successful career in manufacturing.

He was the second-leading rusher for the last NC State football team to win an ACC Championship, way back in 1979. The Forest City, North Carolina, native learned his work ethic picking cotton and garden farming on his grandfather’s land in the Rutherford County foothills, oftentimes with a mule, a plow and a wagon. These were the first steps that brought him on a journey to study animal science at NC State a little over four decades ago.

Now, he’s the founder, owner and CEO of seven companies, including Modular Assembly Innovations (MAI), a $1.2 billion automotive component manufacturing enterprise based in Dublin, Ohio, with more than 350 employees in four states that is ranked in the top five of the 2019 Black Enterprise List of 100 top Black-owned companies in the nation.

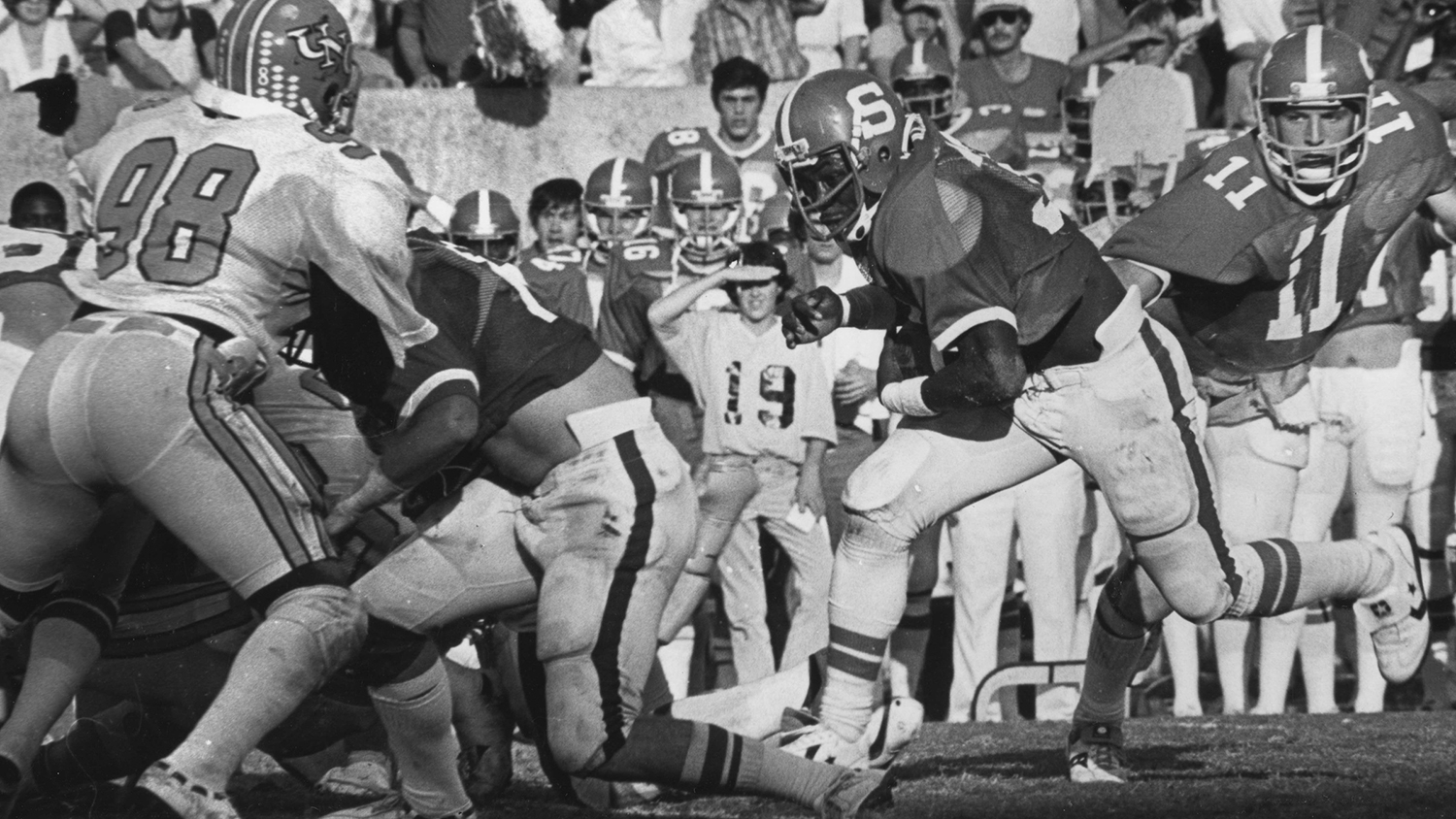

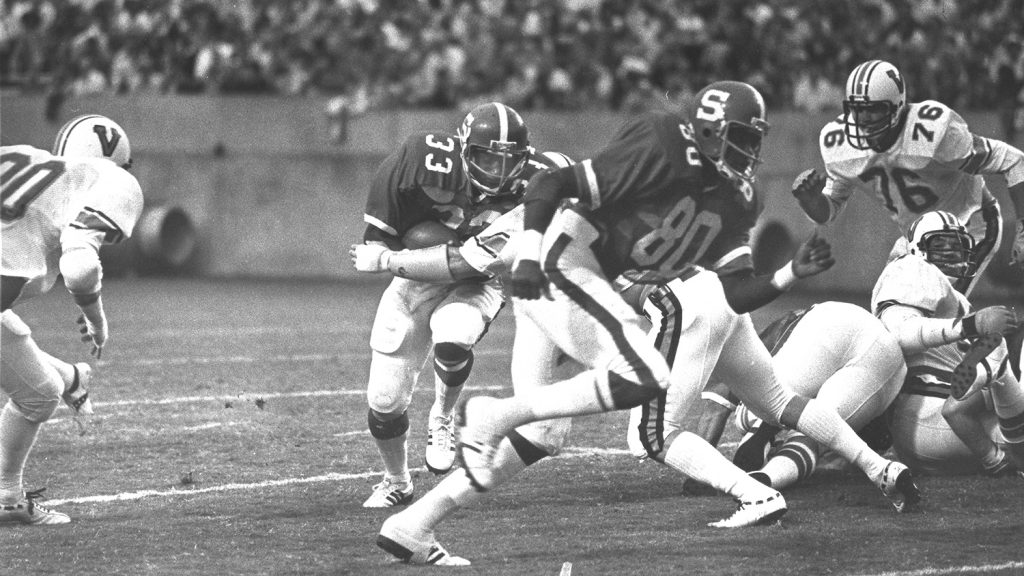

Billy Ray Vickers, one of Lou Holtz’s last recruited football players at NC State and one of the first signees of the late Bo Rein, made his name with Wolfpack football fans as one of the backups and successors to ACC all-time leading rusher Ted Brown, shunning offers from Clemson and South Carolina to become a defensive back because he wanted to carry the football, not defend the goal-line.

In 1979, the year after Brown left for the NFL, Vickers was the Wolfpack’s most frequent option in a tailback-by-committee offensive platoon that actually outgained Brown’s senior-year total and help the Pack compile a 7-4 record en route to the ACC title.

Drive to Succeed

A professional football career did not work out for Vickers, who suffered a torn knee ligament in his next-to-last college game, was drafted and cut by the Washington Redskins and signed and cut by the Baltimore Colts after reinjuring his knee.

So he went back to doing what he learned on the farm and as a football player: hard work. The 63-year-old Vickers says his success is simply the byproduct of a good education, assembly-line sweat and having someone take a chance that a minority business owner could succeed if given the opportunity.

His path to the CEO’s office began by entering a management training program with Corning Electronics in Raleigh, going back to his hometown to work at a brass foundry and making a move to Ohio to work in a steel mill, where he eventually became the plant superintendent. After eight years at the mill, he was hired to run the nation’s largest minority-owned foundry, which made parts for Chrysler.

His entry into automotive manufacturing came in 2004 with a friendship he developed with decorated Vietnam War hero and former General Motors executive Joseph B. Anderson Jr., who has been his business mentor ever since.

“He was a person who had a business operations background, who had been responsible for employees and who I knew was competitive,” Anderson said in a Columbus (Ohio) CEO journal profile. “And there was a level of maturity I saw that said he had the motivation and drive to succeed.”

Anderson was so taken by Vickers that he eventually sold his most successful enterprise to the former football standout in 2011.

A Long Journey

It has been a long journey. Vickers, however, is grateful that Wolfpack football gave him the opportunity to be the first person in his family to go to college and that his NC State education has given him the opportunity to become one of the nation’s top Black business owners.

“As Black Americans, there haven’t always been equal opportunities,” says Vickers, who went to segregated schools until the fifth grade but graduated from fully integrated Chase High School in 1976. “There is equal opportunity to take advantage of education. You don’t just have to have an athletics scholarship to be successful, but that was something that helped me.

“It’s not something I took for granted.”

And while he had obstacles to overcome, as did many Black college students in the 1970s, he found his path at NC State, which first integrated its academics and athletics 20 years before Vickers enrolled.

“I remember taking an African American studies class when I was a freshman,” Vickers says. “Mostly what we talked about were racial relationships. We didn’t actually use the term ‘implicit bias’ then, but it is what we talked about, how we view people, how we relate to each other.

“I’ve always been one to challenge myself to learn about people and where they come from. It could be difficult at times, especially when it came to interracial dating. My wife is white. I am Black. We have shared so much joy together.”

Life Lessons

Joining a football program that was first integrated in 1968 and in an athletics department that developed Black superstars like 1973 ACC Football Player of the Year Willie Burden and two-time ACC Men’s Basketball Player of the Year David Thompson made Vickers feel more at home.

“NC State prepared me for teamwork, from both football and my education, and that prepared me for the business world,” Vickers says. “I had life lessons at NC State, especially the whole racial side of things. In football, we understood how to work together. We understood that we were all the same.

“But it also teaches you that you have to understand the importance of diversity. Our companies always try to recruit people who are different from us. It gives us a different mindset. I would definitely say that’s something I learned at an early age at NC State.”

Vickers also strongly believes in the value of lifting up others and giving qualified companies the resources they need to be successful, the way Anderson did with him.

“There are parts of the Black community where not everyone feels like they have the same opportunities,” Vickers says. “So we have a responsibility to get out in those communities and help teach and help people understand that responsibility. Education is the key if we are ever going to eradicate racial tension, and we have to start that at a young level to make sure there are no educational disparities.”

When Honda was looking to diversify its partnerships, it not only sought out MAI, it gave organizational support to help Vickers and his company to compete with and work with other partners.

“Honda made an effort to work with more minority-owned companies, as did the other big auto manufacturers,” Vickers says. “But they also said if they wanted to grow a strong partnership, they wanted to find a strong company with a background in manufacturing. They didn’t just throw us crumbs, which is what happens sometimes in the business world.

“They helped us scale our company. They gave us the same amount of business as a non-minority company. They gave us training and technical resources. If we had weaknesses, they helped us get better. We were fortunate that they liked … that our philosophy was to put people first, with diversity and inclusion.”

It’s a lesson he’s lived his entire football and business life.

- Categories: