A Day of Infamy, a Time for Heroes

Army radio operator Robert Westbrook ran straight into enemy fire in the opening minutes of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The NC State alumnus lost his life at the airbase on Hickam Field 80 years ago in a courageous bid to protect U.S. bombers on the ground.

Stationed on the most remote archipelago in the world, Pvt. Robert Westbrook Jr. loved to brag to his fellow U.S. Army airmen about catching bream in the ponds and streams of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

He invited them to head east with him with their rods and reels once they had all finished their duties at this “Paradise in the Pacific.”

One quiet Sunday morning — 80 years ago today — those plans changed forever, and Westbrook never returned to his adopted hometown of Raleigh, never attended an NC State alumni gathering and never caught another bream.

A graduate of the Fishburne Military Academy in Waynesboro, Virginia, Westbrook had known for a while his future was in the military. He longed to see the world, as his Methodist missionary parents had done before he was born. His father died when he was an infant and his single mother Mildred Dement Westbrook raised him as best she could while living with family in St. Louis and living on her own in New York, Washington, D.C., and Raleigh.

He had hoped to get an education before he set out on lifelong adventures.

After only one year studying mechanical engineering at NC State College (1938-39), just a few blocks from where he and his mom lived for nearly a decade, he traveled down to Fayetteville’s Fort Bragg to enlist in the United States Army Air Corps as a 19-year-old private.

In military solidarity with her only child, Mildred Dement Westbrook Van Poole took a job as the cafeteria hostess at MacDill Air Base in Florida, her attempt to stay connected to her son half a world away.

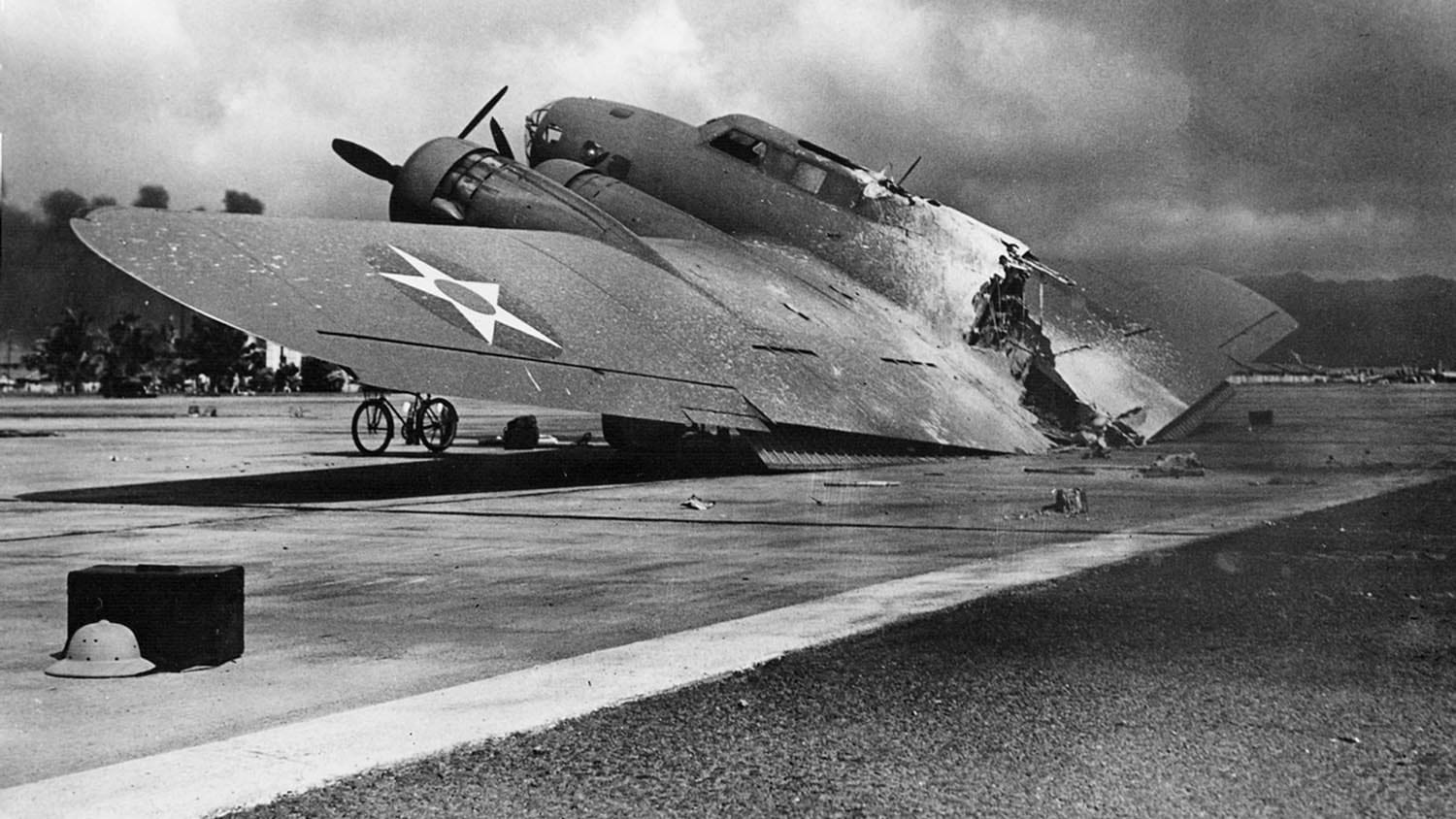

Westbrook became a top-rated radio operator for the 26th Bombardment Squadron on a B-17 Flying Fortress, bragging in a November letter home after getting high marks on his qualification test: “I am proud to be the best radio operator at Hickam Field.”

He closed his letter to his mother, saying “Keep your chin up and remember to be a good soldier.”

On the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, Westbrook rose early for breakfast with his buddy Lonnie Wright, a Texas native and fellow private in his bomber squadron. Shortly before 8 a.m., they were chased out of their bunks after hearing shattering glass and nearby explosions.

It wasn’t unusual. Sometimes the Navy bombers training at the adjacent Pearl Harbor Navy Base on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, missed their targets and shook the airmen at Hickam right out of their beds.

As they ran outside, though, they saw giant red circles on the fighters, horizontal bombers and dive bombers flying overhead. That’s when they realized they, the Pacific Fleet and the United States were under attack by the Empire of Japan and that they were now responsible for protecting the 51 bombers in the Hawaiian Air Force on the ground at the airfield.

For three-quarters of a century, Wright never really talked about what happened to him and Westbrook that morning, but he shared the story with his hometown paper in Kansas, five years ago during the 75th anniversary of the attack.

Their immediate orders were to find gas masks, to protect themselves and their fellow airmen from potential gas attacks, as happened 10 years before when Japan invaded Manchuria, China. They were running unprotected through an empty hangar towards a storage room when a three-seat bomber flew right overhead.

“I felt like we were one of the first ones they took a shot at, because they really hadn’t started attacking us yet [with bombs],” Wright said. “The plane we saw had a big red spot on it. We were just standing there. [The gunner in the back] swung around and starting taking shots.

“There were two bullets that flew right by us.”

Shorter than Westbrook, Wright survived the barrage unscathed. Westbrook, however, slumped over in front of him, instantly dead from an armor-piercing shell in the sneak attack.

“He was right in front of me when the plane came by strafing,” Wright said. “You could hear those bullets coming through the glass.

Westbrook fell and Wright reached down to help his friend.

“I reached down and grabbed him by the shirt,” Wright said. “His shoulders folded and it made me have a sick feeling in my stomach. That was the first time I had ever seen a fresh dead man.

“I looked and in the back of his head was a hole about the size of a nickel. I was right behind him, but I must have been down lower.”

Westbrook was one of 139 Army airmen who died at Hickam Field that morning, including all 35 men having breakfast in the mess hall that was hit by one of the first bombs dropped. He was also the first NC State alumnus, the first registered Raleigh and Wake County resident and one of the first North Carolinians killed in World War II. He is one of 216 known fatalities of NC State alumni and 8,345 North Carolina residents killed in action in the deadliest global conflict in history.

Like the college’s first fatality in World War I, Westbrook died before the U.S. had officially declared war. On Oct. 18, 1916, nearly 18 months before the U.S. entry into the first world war, George Fletcher Sedberry of Fayetteville was among the eight American servicemen who died when the British cargo steamer Marina was sunk by a German U-boat about 30 miles off the coast of Ireland.

Westbrook was spared the horrors of the next four years, while Wright served with the 435th Bomb Squadron. He became a decorated B-29 flight instructor at Great Bend (Kansas) Air Base, where he was awarded the Silver Star, Distinguished Flying Cross, Purple Heart, U.S. Army Air Medal and the Pearl Harbor Survivor medal.

Wright died on Aug. 10, 2018, just three weeks shy of his 99th birthday. He never forgot the morning the bullets began to fly, the bombs began to fall and his best friend died in his arms on a tiny island in the Pacific Ocean.

Mildred Westbrook Van Poole was at work in the cafeteria at MacDill the morning of the attack. She listened with the enlisted men to the reports from Hawaii, worried about the fate of her radio technician at Hickam Field.

She was surrounded and comforted by friends she had made in her four months at the base, all of whom were still impressed that she had received a signed photograph and congratulations from Eleanor Roosevelt just a month after taking the job. She had befriended the first lady while serving as a hostess at an Elizabeth Flynn restaurant in New York.

The next day, Van Poole received a telegram from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s War Department confirming that her son was one of the 2,400 American fatalities during the Pearl Harbor attack.

“He died in defense of his country,” read the telegram.

Westbrook is buried with honors at the National Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, an NC State alum at rest from the surprise attack 80 years ago.

- Categories: