Wildlife Scientists Are Solving Big Data Problems to Track Animals Around the Globe

Using a transmitter attached to a tiny backpack, zoologist Roland Kays tracked an egret – a large, white, wading bird – from North Carolina as it migrated south. Then his data showed the transmitter had stopped moving. Kays wanted to find out what happened, but there was just one problem: The transmitter was in South America.

So Kays offered a reward for information on the bird and successful collection of his transmitter. Eventually, a bird watcher was able to locate it in Colombia. They found the bird died in a marsh. They collected the transmitter and sent it back by mail.

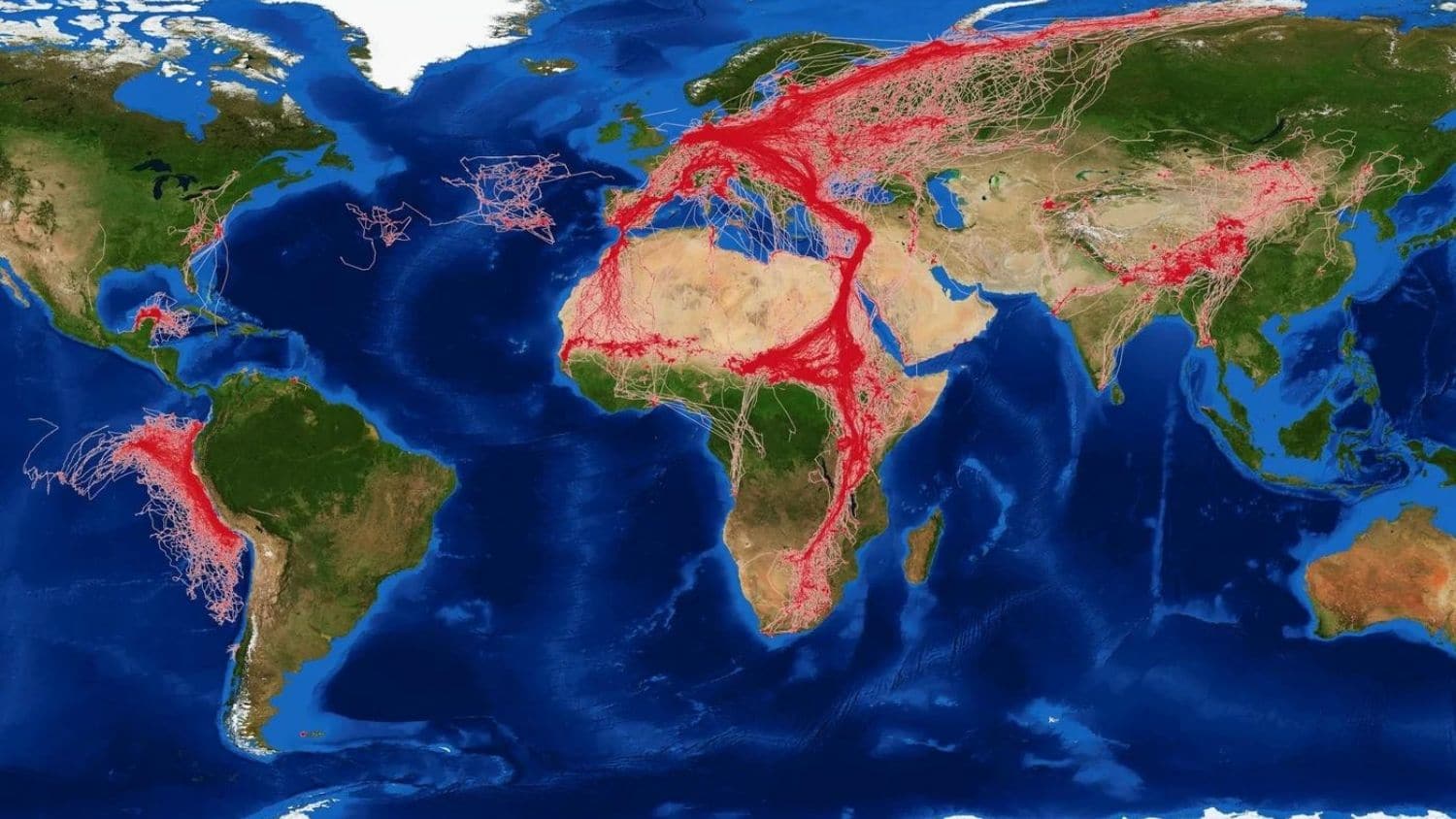

In a new study, Kays and researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and other sites around the world published a paper in the journal Methods of Ecology and Evolution on technology they’ve developed to analyze, visualize and store data in the new “golden age” of wildlife tracking. The study describes Movebank, a free set of tools to help researchers address the big data problems of wildlife tracking. Scientists are already using it to manage more than 3 million new data records generated each day.

Movebank includes an app that allows researchers to connect with citizen scientists and experts on the ground who can help investigate what happened to an animal if a tag goes down. Called Animal Tracker, the app allows researchers to connect with people who can upload photos of animals, make reports, and send in forensic information.

In a case study as part of the study, researchers said they were able to locate downed tags used to track 171 white storks as they migrated across multiple continents. The researchers learned that the leading cause of death varied from continent to continent. While the leading cause of death globally was electrocution from landing on power lines, the leading cause of death in Africa was hunting. They used the app for some of the stork investigation, and expect it could make similar work easier in the future.

“The actual cause of death is important information to get, but it’s really hard to get when the animal is flying over the Sahara Desert,” Kays said. “Having this global system with an app lets us engage with the global community of citizen scientists.”

The Abstract spoke with Kays, research professor at NC State and director of the Biodiversity Lab at the NC Museum of Natural Sciences, about the Movebank study:

The Abstract: How has animal tracking technology evolved?

Roland Kays: The GPS revolution gave researchers a whole new ability to locate animals easily. Then there was another big technology advance where people made really good small solar panels and put them in the animal tracking tags. That gave us more data because you could get more power. We also have accelerometers that are really cool; they let you see how the animals are moving – if they’re running or walking, and what their behavior is.

TA: Why do researchers need Movebank?

Kays: When I was a grad student, I would run around with an antenna and I would collect a few dozen data points a night. Now we’re getting a point every second from lots of animals. You get overwhelmed with data. You need tools to manage the data, the large volume of it, and still be able to do quality control, as well as share and analyze it.

TA: What does Movebank do?

Kays: It’s a massive database of animal movement data from all sorts of animal species and all sorts of different technologies. Any technology you can use to track animals across the globe, we can incorporate that. We now get 3 million new data points per day. We get data from satellites, through phone networks, and we also have people just taking a file on their computer and uploading it. We have a lot of private data and give scientists the tools to protect it; some of the data is sensitive. You don’t want to release the location of where elephants live, for example, because someone might poach them. The scientists own the data; Movebank is a tool they use, and they can share it or make it private.

TA: How could these technology advances help with animal conservation?

Kays: This could really help us identify important conservation corridors, conservation areas, and times of year that are really important. It shows you how animals are dealing with people on the planet; how are they dodging and weaving around people and surviving in a human-dominated planet. That’s what all the research is about these days.

TA: Can the public use Movebank?

Kays: Using the Animal Tracker app, you can go find an animal and take a picture of it, and type in a report of what the animal is doing. There are groups in Europe that are following the storks as they migrate. We are hoping to get a new project with American robins going next year. And the other cool thing now is we can send out an alert so if it looks like an animal has died. If it has stopped moving, we can send an alert asking, “Can someone check on this animal; we think it might have died.” Someone will then use a GPS tracker to find the dead bird or animal. We’ve even had cases where people found live birds that have been stuck and rescued them. In other cases, they were able to determine the cause of mortality.

TA: How can you figure out if an animal has died?

Kays: The most obvious thing is the tags stops moving, but then you can’t be sure if the tag fell off, or just stopped working, so it’s nice to have additional information. For example, the tags can collect a combination of factors including body temperature, and the accelerometer gives you fine scale movement. But ideally you want boots on the ground to do a forensic investigation, and that has to happen quickly.

TA: You can get information about the animal’s death, but what about birth?

Kays: We also have a new app we’re developing to tell if an animal is nesting for example. If a bird is at a nest, it goes back and forth feeding its chicks. And you know how long those chicks, you know the fledging length. If it’s day two, and all of a sudden, the mom has stopped, you know they might (not have made it). It’s pretty cool; you can do that now completely remotely. So we can get information on reproduction and death – the whole life cycle.