Out for Good

Alaina Brennan-Kupec remembers the day everything changed — when she chose to take a public stand against efforts to restrict the rights of transgender people. Learn how she and her wife support trans students at NC State.

The first article I wrote as a student journalist in 1970 involved the momentous question of whether the girls at my Southern California junior high school should be given the freedom to wear pants instead of skirts on campus. The gender norms of the time were so strict that girls were banned from playing Little League and forbidden to work after school as newspaper carriers.

Boys’ choices were constrained, as well. While Hasbro had no qualms marketing the battle-scarred action figure G.I. Joe to boys, Mattel kept Barbie and her fashion-conscious friend Ken on the store shelves reserved for girls.

The memory of those days crossed my mind in the summer of 2016 when I met Alaina Brennan-Kupec, who was fighting what seemed to be just the latest round in the generation-spanning battle to decide how gender expression and gender norms are defined and enforced. We met as a growing tide of anti-queer legislation was moving through statehouses across the country.

“Like most transgender people, I never envisioned being publicly visible,” she told me at the time. “As my wife says, I’m the accidental activist.”

Looking back today, Brennan-Kupec says the decision to take a public stand for equality was no accident, but rather a very deliberate, if difficult, decision. She had transitioned in her early 40s, less than four years earlier. She had a comfortable life in Chapel Hill, with three children and a good job in the pharmaceutical industry to consider.

But the battle came to her.

Taking a Stand

On March 23, 2016, North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory signed House Bill 2, the Public Facilities Privacy and Security Act, into law. Among other things, HB2 required transgender people to use the bathroom that corresponded to their biological sex — the gender assigned at birth — in schools and state-owned buildings.

The next day, Brennan-Kupec spoke against the law at a public rally in Raleigh.

As she and her wife, Kathy, drove east on Interstate 40 toward the rally that day, Brennan-Kupec weighed the potential costs of coming out publicly as transgender.

“I remember thinking ‘This is it. This is me giving away my anonymity, my ability to live a quiet personal life with nobody around me having to know anything about my gender history,’” she says. “The deciding factor for me was my concern for the young people who experience gender dysphoria. The law was making the world much more dangerous for them.”

Shortly after I interviewed Brennan-Kupec in 2016, she appeared in a 60-second public service television commercial advocating for transgender rights. The spot aired during both the GOP and Democratic national conventions that summer.

“It was important to me to shine the light on what it really means to be transgender,” she says today.

North Carolina lawmakers eliminated HB2’s bathroom regulations in March 2017.

Changing the Narrative

Over the next few years, Brennan-Kupec upped the ante. After President Trump announced a ban on transgender people serving in the military in July 2017, she appeared on Nightline and penned an opinion piece for the Navy Times opposing the ban. She served as co-chair of the board of directors of the Transgender Legal Defense and Education Fund until last December, helping grow the organization’s budget and staffing sixfold.

Last year, Brennan-Kupec and her wife gave the NC State University Libraries a major gift on Day of Giving to create the Alaina and Kathleen Brennan-Kupec Transgender Collection Endowment to support a collection of transgender-positive materials.

“The fund for the collection is endowed now, so it will exist in perpetuity,” she proudly says.

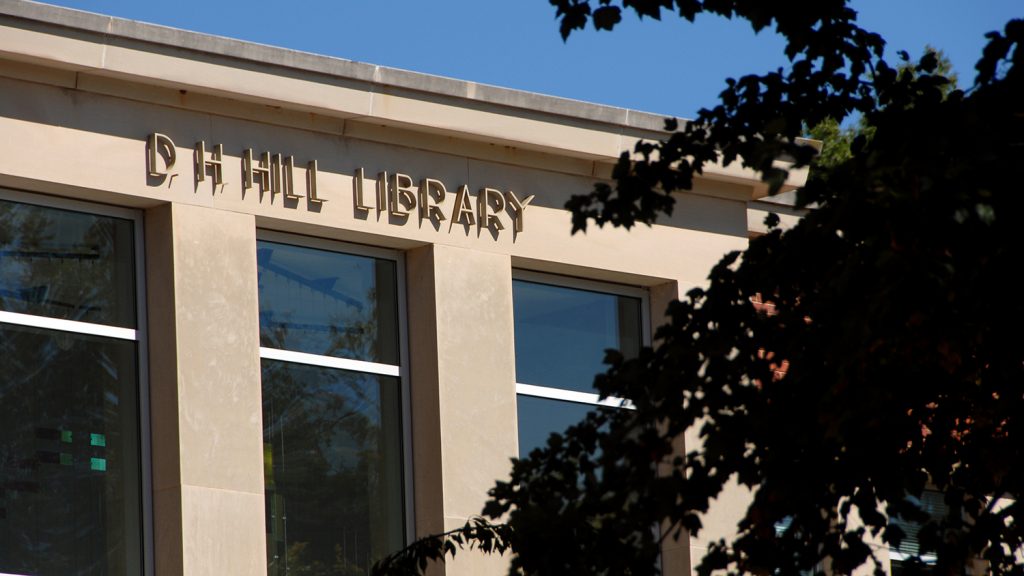

Like her activism, funding the library collection was intentional. It has allowed her to close a circle that began in NC State’s D. H. Hill Jr. Library three decades ago, when Brennan-Kupec — then a Navy ROTC cadet majoring in political science — scoured the book stacks for transgender materials.

There were none.

“I remember feeling demoralized,” she says. “I figured, well, if there’s nothing here, maybe this is all in my head. Maybe I am broken.”

It’s an experience she hopes no one else is forced to endure.

“My hope for this world is that people don’t have to wait until they’re in their early 40s, like I did, to complete a gender transition,” she says. “I want them to complete their gender journey without living half their life feeling ashamed, embarrassed and trapped. I want them to have access to positive information about being transgender and to know that there is somebody out there who knows how they feel.”

- Categories: