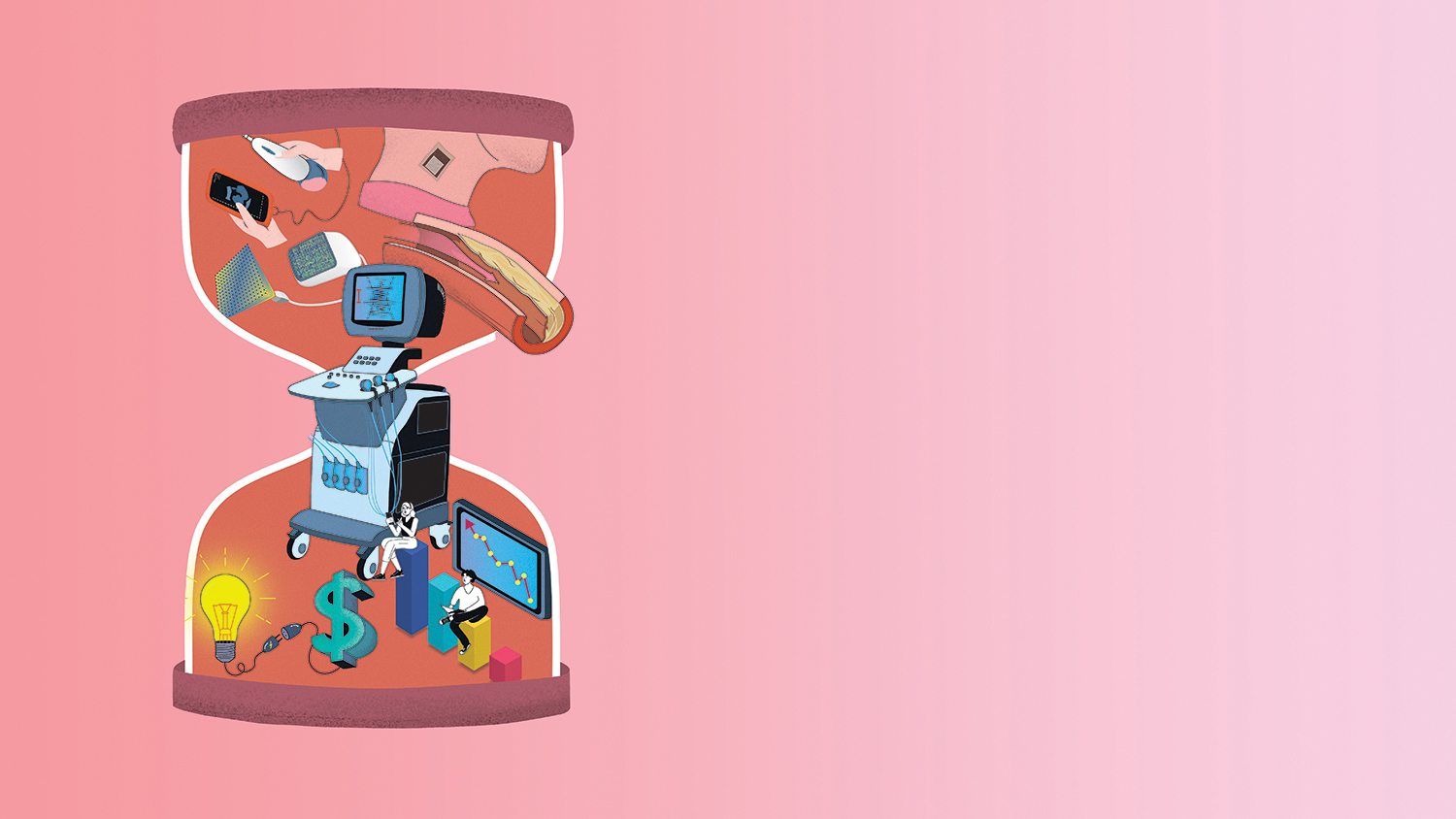

Ultrasound is one of the best-known medical imaging devices. It is safe, cost-efficient and relatively portable, making it one of the most accessible diagnostic and therapeutic medical technologies.

And its potential goes far beyond what it is being used for today.

“I think ultrasound is going to impact public health by providing a lot more information to a lot more people a lot more easily,” said Caterina Gallippi, professor of biomedical engineering. “There’s a term that’s sometimes thrown around, and that’s called the democratization of ultrasound. Meaning that everyone has equal access to it, or at least ready access to it.”

Innovations in ultrasound like handheld devices, wearable sensors and the use of artificial intelligence (AI) are already helping improve access to it. Smaller, handheld ultrasound systems are less expensive, costing as little as $2,000 compared to the $100,000 for a traditional system. More advancements in the field are coming, and to ensure these developments are effectively contributing to the democratization of ultrasound, it’s important for researchers to be factoring in the needs of physicians and patients.

To help prepare biomedical engineers to be better trained in conducting their research and pursuing innovation with end users in mind, Gallippi applied for T-32 funding from the National Institutes of Health — which requires that a program provides unique experiences to students and prepares them to meet critical health care needs — to create a training program focused on ultrasound and entrepreneurship.

The Unified Medical Ultrasound Technology Development (UNMUTED) Predoctoral Training Program teaches students entrepreneurship skills that they can apply to their doctoral research and beyond. The earlier students start thinking about how their research might translate to a commercial space, the more prepared they will be to commercialize their research and make a broader impact.

The program is the first of its kind, and the Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering at North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is the perfect home for it due to ready access to clinical settings and to medical imaging companies in Research Triangle Park.

Selected students do not have to be biomedical engineers, but they do have to be working in a lab focused on ultrasound research. UNMUTED fellows are part of the program for two years. They take two graduate-level courses on technology commercialization and startups, go through several entrepreneurship trainings, shadow physicians in clinical settings to see how they are using ultrasound and complete a summer internship to learn more about industry.

“When [applying for the grant], I had to really think hard about what we are going to offer the trainees in this program that’s different or unique, because really any Ph.D. student who’s studying ultrasound in the Triangle has access to a large pool of expertise, resources and collaborations,” Gallippi said. “And I started to think about not only the environment in terms of expertise in ultrasound, but also in terms of the potential for commercially translating technology.”

Knowing your users

One of the most common reasons a startup fails is because its founders never determined if there was a customer for the technology it created.

That’s a lesson the first two UNMUTED fellows, Ph.D. students Roshni Gandhi and Shureed Deepro Qazi, took away from the National Science Foundation (NSF) Innovation Corps (I-Corps) program.

The immersive I-Corps program focuses on training participants to perform customer discovery, with the goal of commercializing research projects to broaden their societal and economic benefits. Gandhi, Qazi and Gallippi completed the training through Kickstart Venture Services, an Innovate Carolina department that provides entrepreneurial and commercialization resources to research-based startups and the UNC-Chapel Hill community. UNC-Chapel Hill and NC State are both part of the NSF Mid-Atlantic I-Corps Hub.

The UNMUTED team performed customer discovery for a university invention that detects blood viability using ultrasound. They came up with a hypothesis on how the product would help hospitals and blood banks. Rather than pitching their product, they interviewed 20 potential users, asking them unbiased questions about their processes for determining blood viability.

“We learned after interviewing lots of different people, like emergency medical technicians and directors of blood banks, that our product actually didn’t necessarily have a space in that market,” Gandhi said.

Most blood banks and hospitals use an expiration date system to determine blood viability. The researchers found in their interviews that there was little blood being wasted, and that the main problem is a shortage in blood donations.

But just because their product didn’t have a critical need in one market doesn’t mean it won’t be useful somewhere.

“There’s never a negative result [in the I-Corps program],” said Mireya McKee, director of KickStart. “You learn from that. Pivoting is a vital skill that all of us in research and in startups need to learn how to do. Just because something doesn’t work out the way that you’re trying to do it doesn’t mean that there’s not another market out there.”

Making waves in ultrasound entrepreneuership

Emphasizing entrepreneurship is not new to Joint BME. Several faculty members and students have launched startups from their research. Coming up with a way to immerse students in commercialization and entrepreneurship training early in their academic years has been a natural progression.

“The companies that have spun out from BME, the faculty, innovators, the trainees that support the development of the intellectual property, they’re very committed to commercialization,” said Judy Prasad, associate director of KickStart. “They show a strong interest in entrepreneurship.”

As they move forward with their research, both Qazi and Gandhi recognize the value of their early forays into entrepreneurship-based experiences.

“I wanted to get some of the knowledge that it takes to commercialize these technologies,” Qazi said. “For the first couple years of the Ph.D., you’re focused on finishing your classes. And you don’t feel too deep into your research yet, so I thought it’d be cool if I could learn about commercializing.”

The companies that have spun out from BME, the faculty, innovators, the trainees that support the development of the intellectual property, they’re very committed to commercialization…” – Judy Prasad

Qazi, who is part of Gallippi’s lab, is interested in the diagnostic applications of ultrasound and in using machine learning to help decipher imaging results. He is also working on a project on clutter filtering to improve 3-D Doppler ultrasound imaging, which is used to measure blood flow.

Gandhi is a member of BME Chair Paul Dayton’s lab, which has launched several startups. She is currently focused on nanodroplet sonothrombolysis, a therapeutic ultrasound-based technique used to break up blood clots.

“Microbubble sonothrombolysis has been well-studied in the past, and I’m focusing on nanodroplet sonothrombolysis, and that’s more novel,” she said. “There’s a lot more to be done in that field and more that I can discover.”

Ultrasound is only going to become more accessible and easier to use, while its applications continue to grow in two extremes: more advanced computer architecture that enables high-resolution imaging, and more portable, handheld and wearable devices that can be brought anywhere.

UNMUTED will help students have a leg up as they discover their own research breakthroughs that contribute to ultrasound innovation.

“We hope that our students are trained to look at their science with that sort of critical eye,” Gallippi said. “And that they proactively take steps to support the development of that technology toward commercial impact.”

This post was originally published in College of Engineering News.

- Categories: