Reynolds Coliseum: 75 Years of Being ‘Haunted With Greatness’

NC State’s on-campus arena opened 75 years ago with a basketball game against Washington and Lee University on Dec. 2, 1949. It has been in near-continuous service ever since.

NC State’s William neal Reynolds Coliseum is the most important venue ever built by the state of North Carolina, and it always has been ever since the doors opened on the unfinished basketball arena 75 years ago.

Even though the first event in the arena was a Dec. 2, 1949, basketball game against Southern Conference foe Washington and Lee University, the 12,400-seat facility was hardly just for athletics.

In fact, basketball wasn’t even a big deal in the Old North State when designers Milton Small and Ross Edward Shumaker of NC State’s architectural engineering department revealed their plans for the arena, based on a similar design for Duke Indoor Stadium in Durham.

Duke and North Carolina were big football schools at the time, and NC State — which had struggled to maintain its enrollment during the Great Depression — had a part-time basketball coach who doubled as an official for the state highway commission.

State College just wanted a place other than Riddick Stadium to host its Agricultural Week, which had been rained out in 1938, thwarting the opportunity to show off new farm equipment and agricultural advancements to the farmers who traveled from every corner of the state to attend the annual show.

Textile publisher and NC State alumnus David Clark suggested an indoor coliseum to host Ag Week, built on the site of the school’s research barns on the south side of the Southern Railway tracks that bisect campus, as a lasting home for all things agricultural. The proposed facility would have some space devoted to occasional athletics, arts and other activities such as ice skating to pay its operating costs.

Because of the federal funds secured to begin the coliseum’s construction, it was also mandated to be the permanent home for all of NC State’s ROTC programs that taught military science classes and training. The U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force and Marines all call Reynolds home to this day.

So while the Memorial Tower — which was officially dedicated a few weeks before Reynolds opened to remember fallen NC State students, faculty, staff and alumni — is a sacred military memorial, the coliseum has been an active military training center, devoted to the school’s land-grant mission of teaching military science.

For commencement in 1941, student body president William C. Friday announced the purchase of structural steel for the new building during his student address, and seven steel girders were quickly erected on a concrete foundation, on view for all to see.

Construction stopped during World War II, and the building’s skeleton sat dormant until 1948, when coach Everett Case’s success in men’s basketball accentuated the need to restart building.

In 16 short months, the largest arena between New York City and New Orleans was mostly completed and ready for public activities that included basketball, spring commencement and general-admission ice skating on the only ice rink in the South.

Ever since, Reynolds has been a college laboratory for new ideas, different activities and cultural advancement, punctuated in every corner with the pungent smell of popcorn.

The December Rebellion of 1951

A short two years after the on-campus facility opened, things at Reynolds were not going well. Operational costs were higher than expected and the students who had been promised all manner of opportunities for events and activities thought they had been misled by university administration.

On the evenings of Dec. 6 and 7, 1951, exactly 10 years after the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor that forced the United States’ entry into World War II and forced many college-aged men into military duty, State students staged a violent protest in the parking lots of Reynolds Coliseum and in front of Bagwell, Berry and Becton dormitories.

While 10,000 Raleigh residents were inside the coliseum quietly watching two of the weeklong performances of the traveling Ice Capades show, some 300 students, riled and angered, shouted the French Revolution-inspired slogan: “To the barricades.”

Some used rocks from the banks of the train tracks to block the egress routes to Pullen Road. They rolled barrels on top of the barricades and set them on fire. Some punctured and deflated the tires of the fancy cars in the parking lots, and some cut the ignition and radio wires on police motorcycles. Four students were arrested for throwing rocks and damaging property.

College administrators thought they knew why their ROTC-trained students were behaving so poorly at the height of the Korean War stalemate and the Red Scare.

“This has all the earmarks of a communist-inspired demonstration,” said double-world-war veteran Col. John Harrelson, NC State’s first alumni chancellor.

After two full nights of demonstrations, students finally began to reveal why they were so unhappy: too many fees associated with using Reynolds. Some dances cost campus organizations as much as $1,100 for a single event.

Harrelson gathered more than 1,000 students at Riddick Stadium on Saturday, Dec. 8, to let them air their grievances and complaints. He responded in the most academic way possible, commissioning a month-long study and a white paper outlining solutions.

Released in January 1952, the paper was signed by UNC Consolidated System comptroller W. D. Carmichael Jr. and established new rules for the student use of Reynolds.

“College officials notified student representatives that the coliseum service cost charge for the dances would be established at $300 a night, with an additional charge of $50 if a dance made it necessary to remove and replace the basketball floor or ice floor within a period of one week,” Carmichael wrote. “This arrangement received hearty approval and acceptance of the student representatives.

“We have faith that the good sense of our students will assert itself and prevent any further damage to the integrity and good name of State College.”

The end result was that the purpose of the arena was to better serve NC State’s greatest asset, its students, while still opening its doors — originally painted Army-surplus orange and green — for the people of the state.

A Rollicking Reynolds

For more than 50 years, Reynolds was home to NC State men’s basketball. When basketball coach Everett Case was hired in 1946, the coliseum was enlarged while still under construction to 12,400 seats, and in his first 10 seasons it was decorated with nine conference championship banners. Two NCAA men’s championship teams played there, and it has been the home to Wolfpack women’s basketball since the program started in 1973-74.

For years, the university claimed that more people saw events at Reynolds than any other on-campus facility in the country, something that could neither be confirmed nor challenged.

Originally named for tobacco industrialist William Neal Reynolds, thanks to a critical donation of $100,000 from his niece Mary Reynolds Babcock of Greenwich, Connecticut, the coliseum is also called the James T. Valvano Basketball Arena and is home to Kay Yow Court, both in honor of Naismith Memorial Hall of Fame members who coached there.

Basketball, however, was not its sole purpose.

For more than three decades, it was the home of high culture in Raleigh through the Friends of the College program, which brought classical concerts and other culturally advanced performances to campus long before Raleigh had a performing arts center.

The evening of Oct. 30, 1962, was just after the end of one of the most tense events in the history of the world — even more so than the ACC tournament finals three years earlier between NC State and North Carolina. On that night, as the Cuban missile crisis was still playing out, the touring Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra performed Mozart’s Concerto No. 5 and Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony without knowing how the only crowd it faced outside of New York City would react to the geopolitics of the time.

As conductor Gennadi Rozhdestvensky and renowned violinist David Oistrakh finished the final strains of a symphony by a contemporary Soviet composer, the crowd of 13,000 well-dressed patrons stood and cheered in one of the longest ovations in arena history.

For just a moment, Cold War tensions eased, even in the wake of Nikita Khrushchev moving nuclear warheads to the Caribbean island, something that definitely had all the earmarks of a communist-inspired demonstration.

The Guinness Book of World Records twice came to Reynolds to verify marks for its annual publication, first in 1972 to measure basketball player David Thompson’s 44-inch vertical leap and second in 1983 to time junior aeronautical engineering student Ken Blackburn’s record-setting paper airplane flight in the building’s smoke-filled rafters. There is a statue of Thompson now in front of the arena and an occasional airplane flutters from the upper stands during events and rallies.

Beginning in the 1950s, when Louis Armstrong had the first profitable concert in Reynolds’ history, it was a place where rock, pop, jazz and country artists tried out their newest material in front of eager college-aged fans. Everyone from Bob Dylan to Stevie Wonder to Dolly Parton to Olivia Newton-John played in the un-air-conditioned, acoustically questionable facility, at least as long as athletics administrators remained convinced that rowdy spectators wouldn’t ruin the manufactured tartan playing surface or the portable wooden floor that graced the arena for decades. (Athletics director Willis Casey banned rock concerts at Reynolds on three different occasions.)

Although the coliseum was a hospitable venue, sweaty crowds and unventilated corridors made it a difficult place for virtuoso performances.

“It’s just too [expletive] hot,” AC/DC lead singer Brian Johnson once said, not long after singing both “Hell’s Bells” and “Highway to Hell” on Reynolds’ boiling stage. “We were drinking lots of water and I said ‘Cool it lads, we’re all going to die.’”

It was a sentiment felt by many other performers, players and patrons before and since, at least until central air-conditioning was added less than a decade ago.

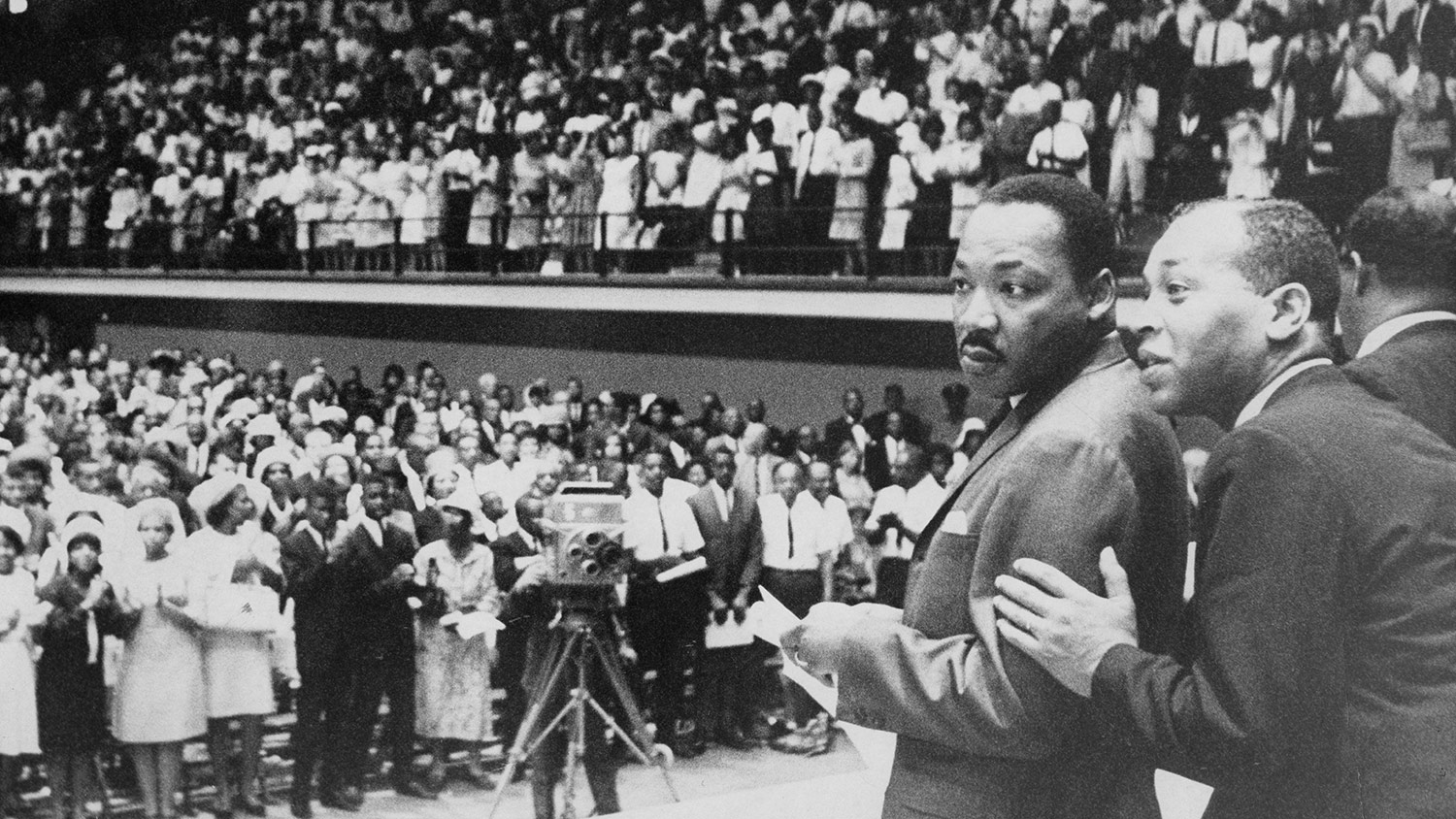

The once-segregated building with separate entries and bathrooms helped set the stage for a removal of Raleigh’s racial barricades in the 1960s, when electrical engineering student Irwin Holmes walked across the stage at Reynolds to become the first African American to receive an NC State undergraduate degree. An even bigger arc of the moral universe bent toward justice on July 31, 1966, when Martin Luther King spoke at a rally on the coliseum floor at the same time the Ku Klux Klan marched in downtown Raleigh.

With its parade of professional basketball and hockey games and its hosting of both men’s and women’s NCAA and Atlantic Coast Conference tournaments, Reynolds was integral in desegregating North Carolina’s capital, starting with the restaurants on Hillsboro Street (as it was then spelled). The Harlem Globetrotters had a standing annual performance there from the first year the coliseum opened throughout the civil rights era.

Hall of Fame basketball player Meadowlark Lemon played his first game with the Globies at Reynolds when he was still attending a Wilmington high school, and one of the team’s halftime entertainers, legendary pitcher Satchel Paige, traveled with the team to talk about his days in the Negro Leagues and Major League Baseball.

Reynolds has been host to presidents, presidential candidates and gubernatorial inaugurations during its lifetime, beginning with the 1960 campaign of candidate John F. Kennedy. Governors Bob Scott and Jim Hunt, both NC State graduates, had inaugural balls on the playing floor of Reynolds, one of which was hosted by North Carolina favorite son Andy Griffith. In 1972, when Spiro Agnew was campaigning for President Richard Nixon’s reelection, attendants from NC State Transportation had the vice president’s limousine towed from the outdoor loading dock at Reynolds’ basement.

Throughout its three-quarters of a century, Reynolds has been at the center of North Carolina’s athletic, cultural, entertainment and political spotlight, a place so hard to leave that twice-retired maintenance worker Billy Ray Dunn has worked there nearly 65 of the 75 years it’s been open.

A Reynolds Renovation

In 2013, NC State facilities and athletics began developing plans for a radical $40 million renovation and closed the building down for 16 months starting in March 2015. All of its permanent residents were moved elsewhere on campus, and home contests for women’s basketball, volleyball, gymnastics and wrestling were conducted at other locations.

“This building gave us life for 66 years,” then-athletics director Debbie Yow said. “We either need to close it or fix it.”

The $40 million upgrade — paid for with funds from the university, athletics and pledges to the Wolfpack Club — significantly reduced seating to about 5,500 spectators; added an athletics Walk of Fame and History; upgraded offices, locker rooms and weight rooms; and finally added the much-anticipated air-conditioning.

In the eight years since it reopened, Reynolds has again served as the center of athletics life, as home for coach Wes Moore’s championship women’s basketball team, Kim Landrus’ ACC champion gymnastics teams, coach Pat Popolizio’s championship wrestling program and Luka Slabe’s volleyball team.

Concerts on a smaller scale have returned to the arena, especially as part of homecoming festivities. Rappers Yung Gravy and Duckwrth performed in 2021, K. Camp with 2 Chainz performed in 2017 and both Lady Gaga and Jon Bon Jovi participated in a political rally on the eve of the 2016 presidential election.

Other standing celebrations in the coliseum that serve the campus community include the NC State Athletic Hall of Fame inductions, Red and White Week celebrations and, before long, a new chancellor installation.

It’s still a place for students, with just enough outside activities and events to remain true to its original purpose. The barns that once stood on the site were long ago rebuilt along Lake Wheeler Road and on the College of Veterinary Medicine’s Centennial Biomedical Campus, and Ag Week is so big now that it has returned to its football stadium roots.

Reynolds still stands as a place that can both celebrate and humble its most successful residents.

Moore, who has guided the Wolfpack women’s basketball team to three ACC titles in the renovated building, remembers one of his first times back in the arena after it reopened. It was after his team returned from beating nationally ranked Florida State in Tallahassee.

“It was dark and I wanted to enjoy the quiet solitude and the history of the building,” says the coach. “All the lights were out. I got a Coke to drink and decided to walk across the floor where so many famous players, important people and well-known performers have been through the years. Reynolds is almost haunted with greatness, and I felt so fortunate to have some alone time in the building.

“What I didn’t see in the darkness was some water that had leaked from the ceiling, and before I knew it my feet were almost over my head and I was lying at center court with my drink in my hand.

“I just decided to stay there, in the dark, and soak it all in.”

Including the puddle of water that made him slip in the first place.

- Categories: