The Masters of Modern

A look back at the university's contributions to modern design, which began almost as soon as the School of Design (now the College of Design) opened its doors in 1948 under the leadership of Dean Henry Kamphoefner.

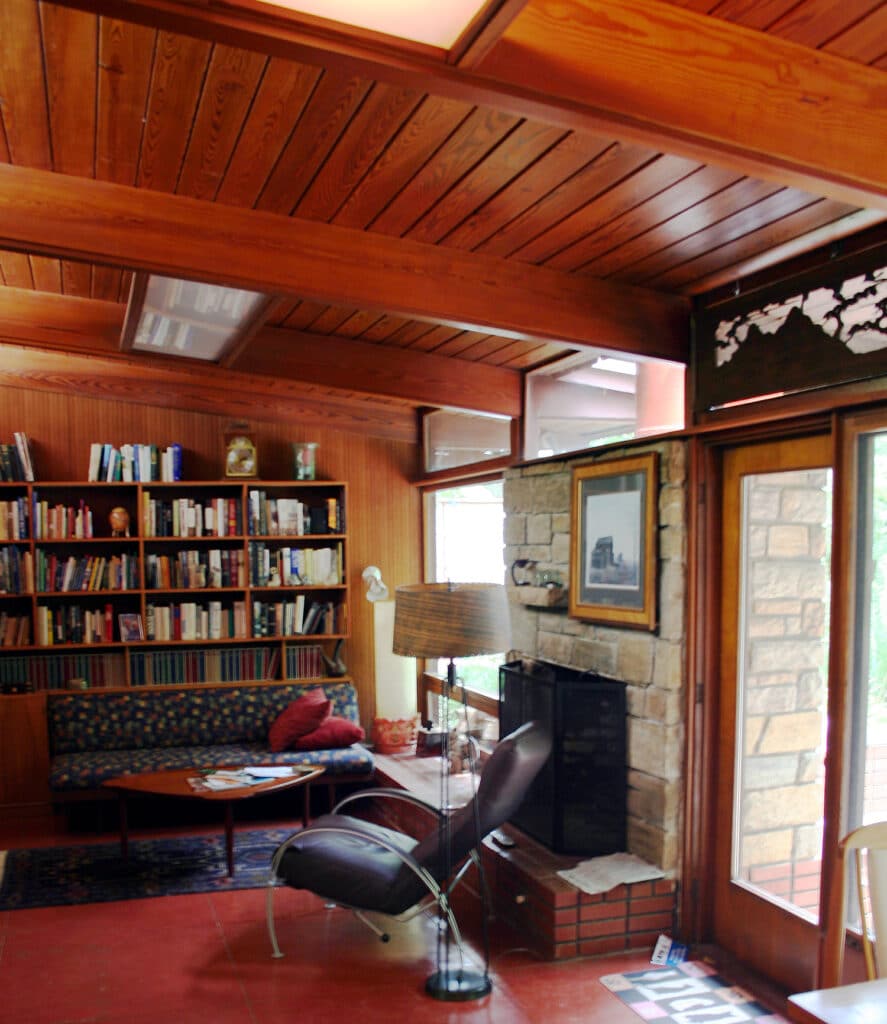

It’s a lazy, humid summer afternoon and a sudden shower breaks the monotony, tapping on the low, flat roof of Bern Walser’s Raleigh home and stranding his cat under a patio table. Walser lounges in a comfortable chair by a large window in the living room, surveying the timeless paradox of suburbia: a lush, expansive garden that threatens to overrun the backyard and a cluster of patio deck chairs that offers an attractive alternative to hard work.

“One of my favorite things about this house is that the outside just comes right in,” he says. “You sit here in this room and feel that you’re out in the garden.”

The single-story house is modest – at 1,900 square feet – and lacks many of the amenities commonly found in new homes, like garden tubs and walk-in closets. But it feels spacious. The living room is long and open, with wide, rectangular windows framing a stone fireplace and rich wood-paneled walls stretching up to a slanted, beamed ceiling.

“I love the simplicity of it, and the clean lines,” Walser says. “They don’t build them like they used to.”

The house has sentimental value for Walser. His father, the late Frank Walser, built the home in 1951 during a long and productive career as a local builder.

The house – called the Ritcher House after the first family that occupied it – has historic value as well. It’s a treasure of mid-century architecture and the product of a burst of creative energy that made Raleigh, for a time, one of the centers of modern design.

In his office in Brooks Hall at North Carolina State University, professor Roger Clark is very much at the crossroads of this history, following in the footsteps – literally and figuratively – of some of the most acclaimed architects of the 20th century, while challenging a new generation of students to chart their own direction into the 21st.

He recently completed a retrospective of the university’s contributions to modern design, which began almost as soon as the School of Design (now the College of Design) opened its doors in 1948 under the leadership of Dean Henry Kamphoefner, who was recruited away from the University of Oklahoma for a salary of $750 a month.

“In many respects it is an unbelievable story – for a state university in a sleepy little city in the South to have created a school that became internationally known in just a few years is astounding,” Clark says. “It was just absolutely amazing. You can go through a list of the most important people in the history of modern architecture and there are not many who didn’t come here, either as visiting lecturers or as professors.”

Kamphoefner recruited young, talented Modernists, luring them to North Carolina with the promise that they could practice their craft as well as teach it. The result was a faculty of working professionals who changed the landscape of Raleigh with bold, experimental designs built on what was then the outskirts of town. A handful remain standing today, including the Ritcher House, designed by George Matsumoto; the Paschal House, designed by James Fitzgibbon; the Kamphoefner House, designed by Kamphoefner and Matsumoto; the Small House, designed by G. Milton Small; the Fields-Fadum House, designed by Fitzgibbon; and the Matsumoto House, designed by Matsumoto (see photo gallery).

The houses share common themes, such as simple, unornamented facades, logical and functional floor plans, and careful integration with the external environment. They were ideal for post-war suburban living, with banks of windows and glass doors opening onto natural stone patios and large backyards.

International Recognition

NC State’s design faculty soon gained national and international recognition for the quality and innovation of its work. Matthew Nowicki, who designed the J.S. Dorton Arena, was selected by the United Nations to design the new capital at Chandigarh, Punjab, India. Eduardo Catalano’s house in Raleigh, with its iconic hyperbolic parabaloid roof, was selected as the “House of the Decade” by House and Home magazine in 1955. Matsumoto was featured in Woman’s Day magazine in 1958 along with his “low-cost dream house.”

Both students and faculty members were influenced by the giants of modern architecture, many of whom made the long trek to Raleigh from Chicago, San Francisco, Paris and Madrid to lecture and teach. Students built geodesic domes with Buckminster Fuller, discussed philosophy (and drank martinis) with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and attended lectures by Frank Lloyd Wright.

“It came together magically at one point,” Clark says. “There’s a certain kind of energy that comes from creating something new.”

It wasn’t just new ideas and acclaimed designs that came out of NC State during that era; some of the university’s most accomplished students came through the School of Design, including Paris Prize recipients Edward Shirley, Bob Burns, Abie Harris, Lloyd Walter and Kenneth Moffett. Two landscape architecture students, George Patton and Dick Bell, received the Prix de Rome, in 1949 and 1951, respectively. And as many as 21 Fulbright Scholarships were awarded to design students during Kamphoefner’s quarter-century as dean of the college.

Some, like Burns, joined the faculty, passing on the principles, skills and knowledge they developed as students to others. Clark, who was hired by Kamphoefner in 1969, says the college has retained the principles that guided it from the start, including the focus on quality and innovation.

“This school, as was the case then, has always been oriented toward the making of things and the development of the craft of design,” he says. “Not all schools are like that. There have been all these movements since the college was founded – post-modernism, deconstructionism and the like – but this school has never been terribly affected by those stylistic changes.”

- Categories: