The NC State College of Veterinary Medicine will debut the largest curricular rework in its history this fall, bringing a five-year collaborative endeavor among faculty, staff and clinicians — many of whom are NC State alumni — to fruition.

“To me, the process of making the curriculum is just as impressive as the curriculum itself,” says Dr. Derek Foster, an associate professor of ruminant medicine and member of the DVM Class of 2004. “This process has been a great model for how curricular redesign can be done effectively.”

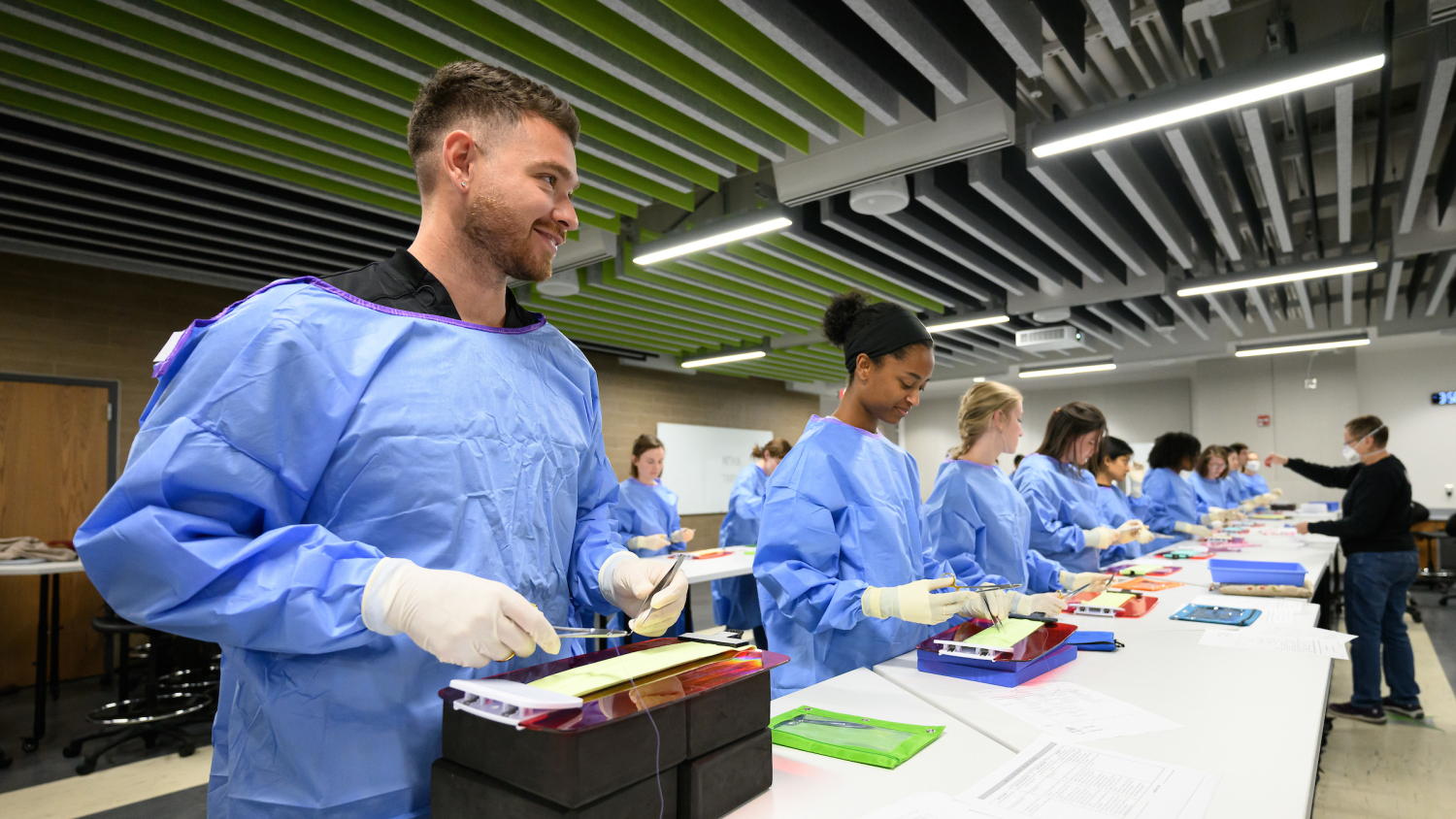

The new curriculum will strengthen the training of tomorrow’s healers by restructuring the course system into focused themes, called “threads,” that better integrate material across years and species, encourage more professional development and provide time for focused clinical skills practice.

The curriculum’s transformation started in 2019 when Dr. Laura Nelson, associate dean and director of academic affairs, and Jesse Watson, director of curriculum and educator development, assembled a team of faculty, alumni and staff to form the Curricular Strategic Plan Steering Committee.

Three stages, countless meetings and a multi-year pandemic later, these architects are eager to share how everything came together.

Crafting the Curriculum

The committee was tasked with identifying what students should know upon graduating from the DVM program and how they master that information. During this process, the group consulted members of the veterinary community and organizations, including the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges and the International Council for Veterinary Assessment, to evaluate what benchmarks they set for graduates.

The team found students needed to not only understand veterinary medicine across species but also develop professional dispositions, or behaviors and attitudes, that equip them for medical practice.

“It’s not just, ‘What do the students know and what can they do?,’ but, ‘Who are they as veterinarians?’” Watson says. “What kind of a professional are we hoping to inspire? These are not skills that are trainable in the same way. It’s more like gardening. You’ve got to figure out how to plant the seed and provide resources to help students grow in that direction.”

The next step was evaluating how well NC State prepared students to reach those benchmarks. In the fall of 2019, a separate Curricular Strategic Planning Committee began comparing the college’s existing curriculum to standards set by the American Veterinary Medical Association Council on Education, peer institutions and other professional organizations, and then identifying how NC State could improve.

“We determined that the content we wanted was there, but there was a lack of organization of the content between and within courses,” Nelson says. “The organization wasn’t necessarily in place to naturally help a learner use that information. There wasn’t a lot of built-in integration of skills and knowledge, and veterinary practice is a combination of both.”

Curricular Strategic Planning Committee members also reviewed feedback from other students and staff during this stage. They discovered courses could feel siloed, meaning students could have difficulty connecting what they learned in one course or year to another because the classes were organized by discipline and species.

In addition to scrutinizing course content and structure, members reviewed the college’s “hidden curriculum,” or its implicit teachings, and found opportunities to boost student well-being holistically.

“The curriculum is what students experience when they come to this school,” Nelson says. “It’s their interactions with faculty and staff, the quality of the support they have through advising and student services, and their interactions with one another in the social environment. All of those things are part of the student experience here, and all of them are going to cause learning.”

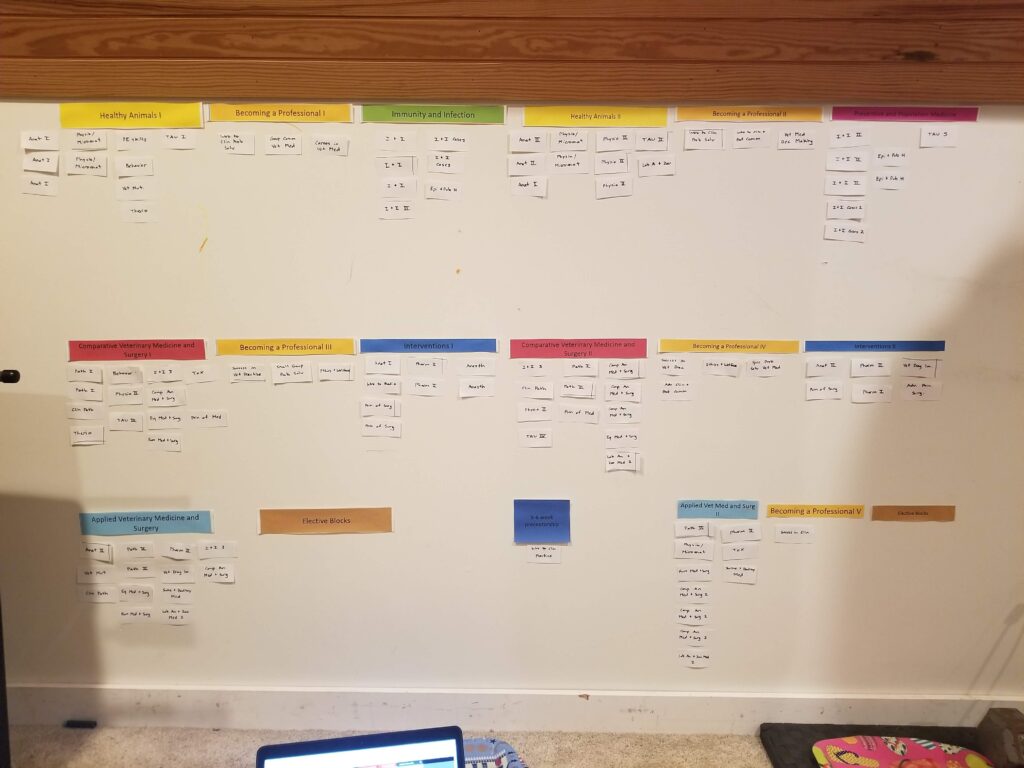

Faculty members proposed about a dozen different models for the new curriculum structure that integrated these strengths and addressed the challenges, Watson says.

They ended up with five finalists for the new curriculum. The vote came down to two proposed by College of Veterinary Medicine alumni: Foster and Dr. Katie Sheats, an associate professor of equine primary care.

Both models involved structuring the material into threads based on body systems and processes across species, Foster says, but Sheats’ model incorporated an experiential requirement in students’ third year.

“I think it’s great that Derek and I ended up with the top model choices since we are both NC State College of Veterinary Medicine alumni,” says Sheats, who graduated from the DVM Class of 2005. “While the names we gave our threads were different, the models were very similar.”

The committee picked Sheats’ design and collectively refined her model to incorporate other suggestions. In Sheats’ structure, she says, the threads group content from previous courses into themes that connect both what students are learning and how they are learning it.

“The design ensures that students are going to revisit subjects multiple times, with increasing complexity over time, and that growth is an expected part of the journey,” Sheats says. “Each thread has a name that helps with the understanding of what all of the content in there is building in terms of knowledge, understanding, skills, abilities and professionalism. I’m really excited about it.”

The new curriculum’s five threads group the same core material from dozens of individual courses and disciplines into larger themes. The threads are Animal Health and Disease, Becoming a Professional, Exams & Interventions, Form & Function and Integrated Applications.

Each thread encompasses an essential knowledge basis and skill set for practicing veterinarians. Watson says this structure supports comparative medicine, or the ability to think across species, and aligns with the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges’ competency-based veterinary education model.

In NC State’s curriculum, course material will be organized into a “spiral” format that encourages student learning and application.

“A spiral curriculum is a curriculum that is designed to, over time, revisit and build on learners’ previous knowledge and experience,” Sheats says. “The design allows educators and students to create more connections between different curricular content that can seem disparate to the learner, but really isn’t once the learner becomes more advanced.”

More Changes Coming

Another curricular addition from Sheats’ model, the preceptorship, encourages students to put their learning into practice. The program will be a four-week workplace-based experience for third-year students at an outside organization where students will hone their professional development, clinical reasoning and communication skills.

“It’s an important step in building student confidence for them to be able to experience success and get feedback from the professionals that will employ them when they graduate,” Sheats says. She adds that College of Veterinary Medicine educators will use feedback from preceptors to inform their teaching.

The new curriculum also aims to improve the overall student experience.

During the review process, students said the school could further support their mental health in a challenging program. College of Veterinary Medicine leaders began improving the advising program by training additional faculty to be advisers and providing them with more mentorship tools, Nelson says.

The new curriculum continues to offer faculty opportunities to grow as world-class educators by encouraging them to further their training and pursue leadership opportunities in veterinary education. Faculty embrace these resources, Watson says: NC State instructors comprise about a quarter of the new leadership of the Academy of Veterinary Educators.

“We have stressed that if you’re going to be a teacher, we would love for you to learn more about teaching and to explore that identity, and we’re here to help you do it,” Watson says. “We have one of the strongest cadres of veterinary education in the United States.”

An ‘NC State Flavor,’ Thanks to Faculty

Of course, this curricular evolution would have been impossible without the faculty who bring it to life in their classrooms.

Professors and clinicians from across the college led the task from the beginning. Their input throughout the process makes the new curriculum stronger and more representative of the diverse perspectives and experiences across the College of Veterinary Medicine, Nelson says.

“This new curriculum really has an ‘NC State flavor,’ ” she says. “It reflects the priorities, the culture and the clinical expertise we have here that is unique to our college.”

Sheats and Foster are involved with veterinary education organizations across the country and have seen faculty from other colleges struggle to navigate curricular change. NC State’s process is exceptional because it has been so cooperative, intentional and accepted, they say.

“This college is a family, and you want the feeling of belonging and inclusion to be at the heart of that family,” says Sheats, who earned her bachelor’s, master’s, DVM and Ph.D. degrees from NC State. “Giving faculty voice and input to the design of something as big as a new curriculum invites that. NC State has just done a phenomenal job at being collaborative throughout this process.”

This post was originally published in Veterinary Medicine News.

- Categories: