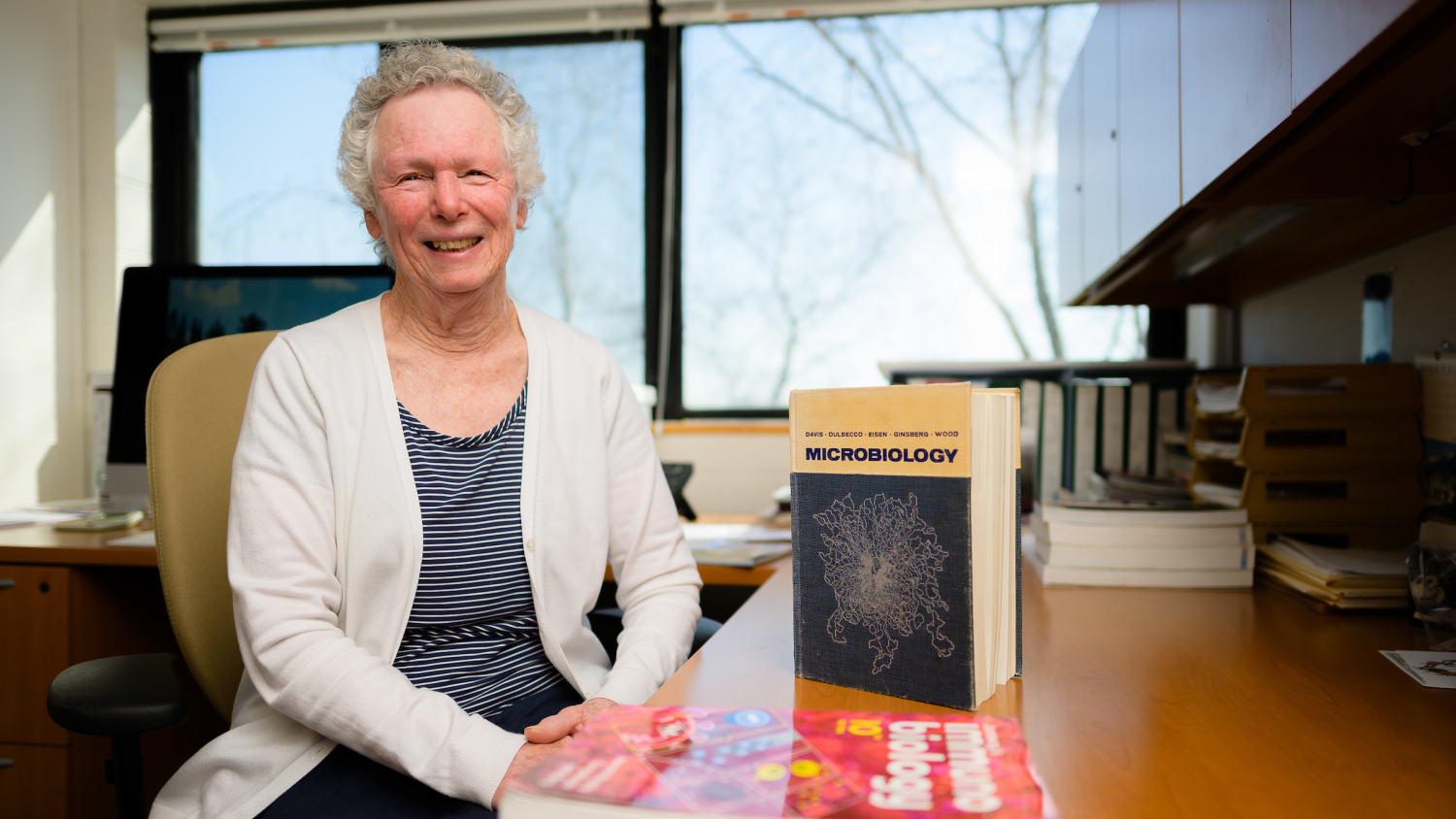

Dr. Susan Tonkonogy’s 54-year career in immunology began at a college whose flagship university did not yet admit women.

Tonkonogy earned her bachelor’s degree in bacteriology from Douglass College, the women’s division of Rutgers University in New Jersey, in 1970, two years before Rutgers became coeducational. She remembers just two female professors and about 10 students in her major.

The trailblazing female scientists who taught Tonkonogy and learned alongside her inspired her lifelong love of immunology and showed her the possibilities of a career in science academia.

“There have always been amazing women in immunology, but there weren’t many back then,” says Tonkonogy, now the longest-tenured active faculty member at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine. “They were certainly not half of the field.”

Tonkonogy has since become a role model for other women finding their footholds in the biological sciences. She joined the College of Veterinary Medicine faculty in February 1982, during the college’s first spring semester, as the first female faculty member in what is now called the Department of Population Health and Pathobiology.

At NC State, she has advanced medicine’s understanding of gastrointestinal health and disease through her research on the immune system’s role in intestinal inflammatory conditions and helped thousands of DVM students across 40 graduating classes and countless graduate students understand a complex medical discipline.

As Tonkonogy reflects on her career ahead of her retirement this summer, she is grateful for the progress she has seen at the college and in the broader scientific community to better support women pursuing careers in the sciences.

“The NC State College of Veterinary Medicine is an absolutely wonderful place to be a faculty member and a scientist,” she says. “And it’s so nice to look out over a sea of students and see so many more female faces than when I was studying. There are also many more women to look up to now.”

Training in a Changing Field

Originally from Montclair, New Jersey, Tonkonogy started at Douglass College interested in science but unsure what specialty she wanted to study. A captivating instructor in her advanced microbiology course helped change that.

“Dr. Cook would often start our class by saying, ‘I read something so fantastically interesting about how the immune system works and the mysteries of its functions, and I’m going to tell you today about what we know and especially what we don’t know,’” Tonkonogy recalls. “She was so enthusiastic, and I started thinking, ‘I want to be involved in a subject in which there are so many unanswered questions that I could help answer through research.’”

She moved to Boston after graduation and began working as a research assistant in immunology at Harvard Medical School. While there, she learned the school was starting a new Ph.D. program in immunology and enrolled in its first class, completing her Ph.D. in 1976.

At Harvard, Tonkonogy saw firsthand how her generation was making the field more inclusive. She remembers no female immunology professors from her graduate program but plenty of female students and postdoctoral researchers who supported one another.

“Many of the students and postdocs did look like me, but at the time, we did not dwell on the obvious issue that the faculty didn’t,” she says.

Women have furthered the fields of immunology and microbiology since at least the late 1800s, but historically their contributions have been under-recognized compared with those of male peers.

A 2020 National Institutes of Health study published in Nature Immunology found that female scientists are still underrepresented and underfunded in faculty and leadership positions, despite comprising the majority of microbiology, immunology and virology trainees. Another study co-authored by Dr. Laura Nelson, an NC State College of Veterinary Medicine associate dean, in 2023 reported that male veterinary college faculty tended to hold higher odds of more advanced academic rank and that female faculty more frequently reported their gender disadvantaged their careers.

These studies propose that reallocating resources equally, boosting mentorship and advocacy efforts and challenging gender-based stereotypes can improve gender parity in the sciences. Tonkonogy’s career is a testament that making strong connections with supportive and inclusive advocates makes a difference.

After earning her Ph.D., Tonkonogy worked as a postdoctoral research fellow at the Swiss Institute for Experimental Cancer Research in Lausanne, Switzerland, from 1977 until 1979. She learned to master a new technique that would revolutionize scientific research and disease diagnosis, namely producing monoclonal antibodies.

She then spent a month as an immunology instructor at the World Health Organization Research and Training Institute in Sao Paulo, Brazil, before returning to the United States for a position at Duke University Medical Center’s immunology division in 1979. There, she worked as a postdoctoral fellow and later a medical research associate producing monoclonal antibody reagents that would expand the capacity to test tissue compatibility in organ transplants.

“At the time, there were very few immunology labs, and you generally went somewhere on the basis of some personal association,” she says of her arrival at Duke. She applied there at the suggestion of a female postdoc she knew from Harvard whose Ph.D. mentor headed the lab.

Three years later, friends on NC State’s faculty encouraged Tonkonogy to apply to the newly established College of Veterinary Medicine, and Tonkonogy found herself trading Duke blue for Wolfpack red.

Four Decades of Impact

When she interviewed at NC State, Tonkonogy remembers, administrative assistant Alice Dorsey was the only female department employee available to accompany her to lunch with department head Dr. Leroy Coggins.

By joining what was then the Department of Microbiology, Pathology and Parasitology, Tonkonogy helped diversify the faculty pool in another way: She had a Ph.D. but not a DVM.

“The dean, Dr. Terry Curtin, and Dr. Coggins appreciated that veterinary medicine is science, in addition to practice,” Tonkonogy says. “They equally valued basic research, applied research and clinical work.”

The college looked much different back then. Tonkonogy says faculty from across departments had adjacent offices so they could easily collaborate on multidisciplinary projects. Classes were nearly three times smaller, with 40 students — 20 men and 20 women — in the first cohort.

“Our first students were just outstanding,” Tonkonogy says. “They were so eager to learn, because they had been waiting for a veterinary school in North Carolina for so long. Immunology is a very abstract discipline, but I remember students were so interested and excited about learning it. That was just a wonderful way for me to start an academic career.”

Dr. Hilda “Scooter” Holcombe, DVM Class of 1987, says Tonkonogy’s passion for immunology is infectious. She met Tonkonogy as an NC State undergraduate, worked in her lab every summer during vet school and studied under her for her master’s and Ph.D. in immunology.

“I worked with her every chance I could,” says Holcombe, a retired associate director of lab animal medicine at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “I fell in love with immunology largely because she’s so enthusiastic and hands-on about it. To this day, anytime I’m doing any immunological research or training people, I’m still teaching them ‘her way.’ She’s the expert, as far as I’m concerned.”

Tonkonogy also appreciates the support the college has given her for her research throughout the years.

Often working with colleagues in the collaborative Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease, which is approaching 40 years of continuous National Institutes of Health support, Tonkonogy has extensively studied immunity and inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract, focusing on the immune response to intestinal microorganisms in inflammatory bowel diseases, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

“Her true love is really the science itself,” Holcombe says. “I’m enjoying retirement, but I get together with her and I get all excited about immunology again. It’s an amazing trait for somebody to be that enthusiastic about and happy with their career for so long.”

Even after 42 years, Tonkonogy still looks forward to coming to the college every day and inspiring a love of immunology and academia in her students and colleagues.

“To me, there’s absolutely nothing that can match an academic career,” Tonkonogy says. “For women entering the field now, I say, ‘We did it, and you can, too.’”

This post was originally published in Veterinary Medicine News.

- Categories: