5 Questions With Richard Ford

When Richard Ford was a teenager, he knew what he wanted to be when he grew up: a hotel manager. Ford even went to Michigan State so he could enroll in the university’s highly regarded hotel science program. As it happened, he changed career paths a number of times — schoolteacher, science editor, law school student, ROTC cadet — before he decided to try his hand at writing fiction. He got a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing, tried and failed to get any of his short stories published, and had only modest success with two novels that did find a publisher.

That’s when Ford decided to quit fiction writing and become a sportswriter for Inside Sports magazine. That lasted a year until the magazine folded. He then applied for a job at Sports Illustrated; they didn’t hire him. At that point Ford did the only thing he could think of to do: he wrote a novel about a man who had abandoned a career as a fiction writer to become a sportswriter.

That novel, “The Sportswriter,” went on to become one of Time magazine’s five best books of 1986. His novel “Independence Day,” a sequel to “The Sportswriter,” is the only book to ever win both the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the PEN/Faulker Award. Since then he has published a number of critically praised and commercially successful books and story collections, most recently the novel “Canada” (2012). He may not be a hotel manager, but fiction writing seems to suit Richard Ford just fine.

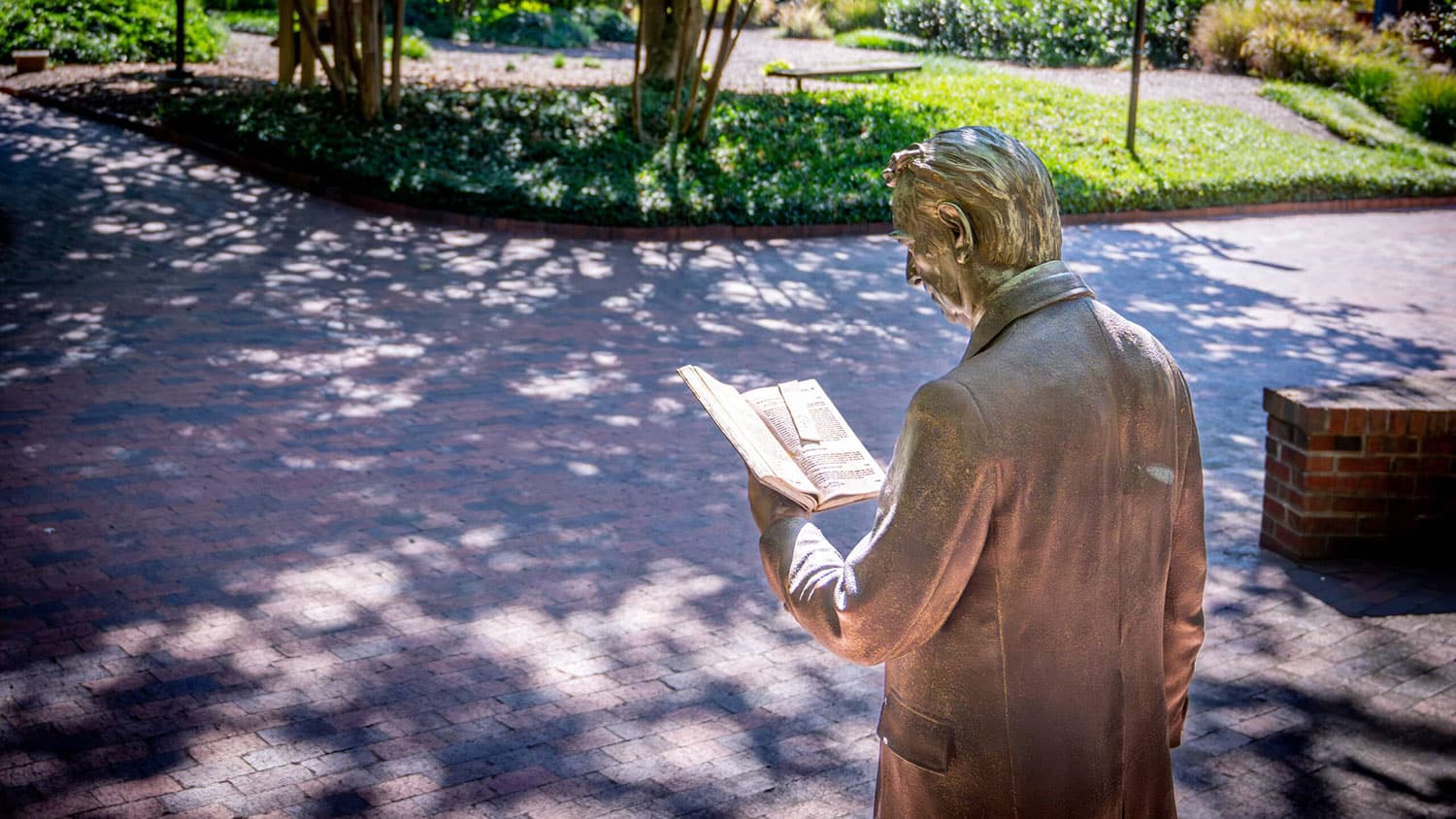

Ford is coming to NC State as part of the North Carolina Literary Festival, which will take place at the Hunt Library April 3-6. He will give a keynote address in the library’s Multipurpose Room at 1:15 p.m. on Sunday, April 6. Note: Ford’s keynote is a ticketed event. Tickets are free and are available from Quail Ridge Books & Music in Raleigh and at go.ncsu.edu/nclitfest-ford.

In an interview this week, Ford talked about what it means to win a prize, the appeal of sportswriting, and the future of reading, writing and literature.

You’ve won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, one of the most prestigious awards an American writer can win. Did winning the Pulitzer change your sense of yourself as a writer, or the way you view your writing?

Good luck’s never bad (except for neurotics). Winning the Pulitzer Prize was a happy event. It made me feel encouraged to go on being a writer; it flattered me shamelessly; and it made my wife Kristina, who’s deeply involved with everything I do, feel very good. I was already happy, though, with how “Independence Day” had fared in the world. I didn’t think I was a better writer because of winning that prize. When one wins a prize it always means that, for some unfair reason, somebody probably better didn’t win. That’s just the deal. You can’t let it reconfigure who you think you are.

I think your short story “Optimists” is a brilliant example of the form, so when I read “The Sportswriter,” I was surprised by how different the two pieces are: the working-class grimness and sparer sentences of the short story compared to the comfortable suburban setting and more loquacious style of the novel. Did either one of these styles and tones feel closer to your “natural” style, if you have one? Did either one feel like more of a stretch?

I don’t believe (for myself) in a “natural” style. For most writers — for me, definitely — all style is artifice. All is a stretch, although not necessarily a difficult stretch. We all have different voices spinning around in our heads, different modes of address we use for different purposes. Writers just have something particular to do with those voices. One tries to manufacture a voice, a persona, a tone, a diction, a grammar that permits oneself to get everything of importance plausibly, interestingly down onto the page.

You’ve said before that if Inside Sports hadn’t folded, you’d probably still be a sportswriter, and you’d probably be happy that way. Since you started writing fiction, you’ve also taught at a number of universities, and now you teach in the creative writing program at Columbia. So I just have to wonder, which do you like better — teaching college or being a sportswriter?

They each have their small appeals. I still occasionally write about sport(s). And I still feel that if I’d stayed a sportswriter, I’d have been happy. I never, on the other hand, conceived of teaching as a steady job. I’ve only done it, in total, seven years out of 45. Over time, that’s been about my saturation point. It’s a noble profession, but I really wasn’t trained for it. All I know how to do is read, which is what I teach at Columbia.

Are you working on another project now?

I’m just this week finishing a book of four long stories narrated by Frank Bascombe, the narrator of “The Sportswriter” and “Independence Day,” set in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

The theme of the 2014 North Carolina Literary Festival is “Discover the Future of Reading.” What do you think the future might hold for the reading public?

If I could look into a crystal ball, I’d first look for something more exotic, believe me. Books as we know them will soon be antiquarians’ business — the exception rather than the rule. I don’t really care because writers are going on writing, and readers (using some delivery system or other) will go on reading. Literature delivers something we need, an extra beat to life, an affirmation that life’s worth our interest, a delight in the language we use every day. I’m not very worried about those needs not being met by some sort of literary gesture.

- Categories: