Racing to Stop the Cankerworm

Controlling cankerworms is tricky, but on a foggy Friday, entomologist Steve Frank and his colleagues head out on their weekly mission: preventing the cankerworm, an annoying pest, from defoliating North Carolina’s urban deciduous trees.

In the fall Frank and undergraduate researcher Noukoun (Bobby) Chanthammavong and technician Greg Bryant, laid traps on 36 willow oaks across campus by using tape covered with Tanglefoot, a sticky paste used to prevent pests from feeding and laying eggs on trees. Each week the team tallies how many cankerworm moths succumb to the sticky bands. On this day alone 1,955 were counted, bringing the 2013 total to almost 12,000.

“We’re making good progress,” Frank says, carefully extracting the critters with a twig.

Progress is good because the clock is ticking. Last spring thousands of cankerworms infested trees across the northeast. Cankerworms even cast sticky webs across NC State, freaked out pedestrians, and on some trees demolished up to 75 percent of the leaves. Panicked arborists and landscapers across North Carolina called Frank at the Urban Ecology Lab.

“Nobody knew what to do,” says Frank. “Everyone worried. While healthy trees can withstand one year of defoliation from cankerworms, if this continues trees will die.”

Innovative Solutions

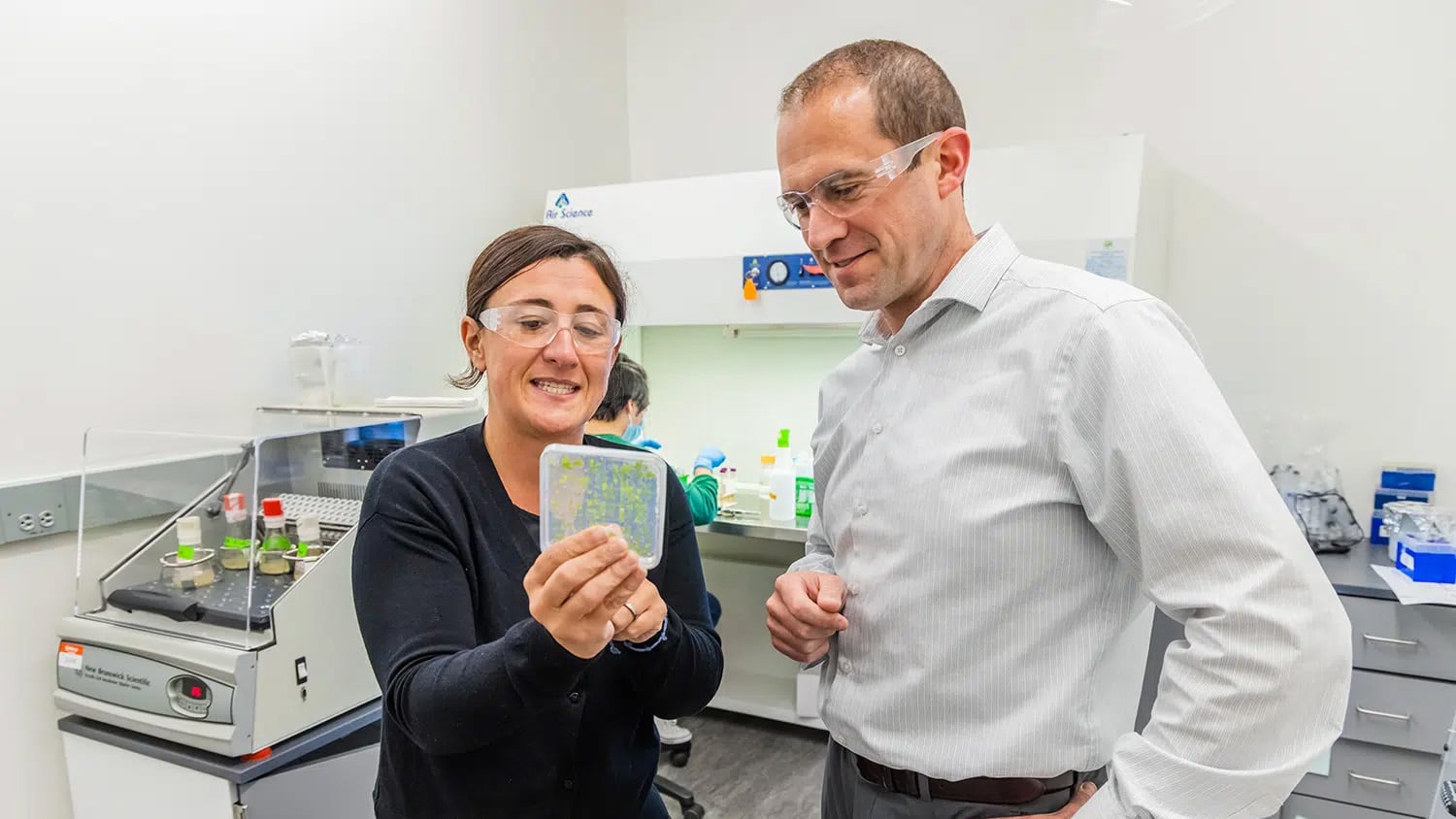

As an assistant professor of entomology and an N.C. Cooperative Extension specialist, Frank’s job is solving community problems like this.

He knew cities used non-toxic insecticide to reduce cankerworms in the past, but preferred the sticky bands—because they are cheaper and easily duplicated.

The scientists were challenged also by the cankerworms’ life cycle. Cankerworm eggs hatch in early spring and feed on leaves for five to six weeks before spending the summer pupating in mulch and leaf litter on the ground.

“By the time you notice the defoliation, it’s too late, the tree is stripped—our goal is intercepting that cycle,” Frank says.

Frank is also exploring whether the recent cankerworm plague resulted from rising urban temperatures and milder winters. So tree temperatures are being monitored along with whether trees with one or two bands capture the most moths, Frank adds.

“Ultimately we want to offer specific recommendations to landscapers, arborists and residents on how best to control the pest.”

Great Efforts Yield Great Results

Frank is encouraged by the findings so far and by a weak spot in the cankerworms’ life cycle: the moths are wingless. So when cankerworm adults emerge from pupae they climb, not fly, up the tree to lay eggs in the twigs before dying. Preliminary findings show the sticky tape prevents them from getting to the branches and laying eggs.

“No eggs in the branches, no caterpillars, no defoliation,” Frank says. “It’s a pretty simple concept—we hope it works.”