Researchers Find Nanowires Have Unusually Pronounced ‘Anelastic’ Properties

For Immediate Release

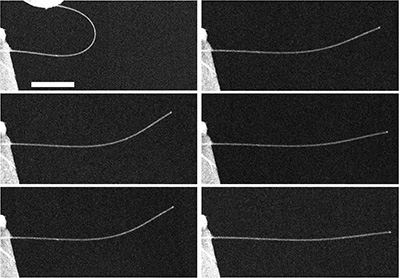

Researchers from North Carolina State University and Brown University have found that nanoscale wires (nanowires) made of common semiconductor materials have a pronounced anelasticity – meaning that the wires, when bent, return slowly to their original shape rather than snapping back quickly.

“All materials have some degree of anelasticity, but it is usually negligible at the macroscopic scale,” says Yong Zhu, an associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at NC State and corresponding author of a paper describing the work. “Because nanowires are so small, the anelasticity is significant and easily observed — although it was a total surprise when we first discovered the anelasticity in nanowires.” The anelasticity was discovered when Zhu and his students were studying the buckling behavior of nanowires.

“Anelasticity is a fundamental mechanical property of nanowires, and we need to understand these sort of mechanical behaviors if we want to incorporate nanowires into electronics or other devices,” says Elizabeth Dickey, a professor of materials science and engineering at NC State and co-author of the paper. Nanowires hold promise for use in a variety of applications, including flexible, stretchable and wearable electronic devices.

The researchers worked with both zinc oxide and silicon nanowires, and found that – when bent – the nanowires would return more than 80 percent of the way to their original shape instantaneously, but return the rest of the way (up to 20 percent) slowly.

“In nanowires that are approximately 50 nanometers in diameter, it can take 20 or 30 minutes for them to recover that last 20 percent of their original shape,” says Guangming Cheng, a Ph.D. student in Zhu’s lab and the first author for the paper.

The work was done using tools developed in Zhu’s group that enabled the team to conduct experiments on nanowires while they were in a scanning electron microscope. Additional analysis was done using a Titan aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope in NC State’s Analytical Instrumentation Facility.

When any material is bent, the bonds between atoms are stretched or compressed to accommodate the bending, but in nanoscale materials there is time for the atoms to also move, or diffuse, from the compressed area to the stretched area in the material. If you think of the bent nanowire as an arch, the atoms are moving from the inside of the arch to the outside. When the tension in the bent wire is released, the atoms that simply moved closer or further apart snap back immediately; this is what we call elasticity. But the atoms that moved out of position altogether take time to return to their original sites. That time lag is a characteristic of anelasticity.

“This phenomenon is pronounced in nanowires. For instance, zinc oxide nanowires exhibited anelastic behavior that is up to four orders of magnitude larger than the largest anelasticity observed in bulk materials, with a recovery time-scale in the order of minutes,” says Huajian Gao, a professor at Brown University and co-corresponding author of the paper. Detailed modeling by Gao’s group indicates that the pronounced anelasticity in nanowires is because it is much easier for atoms to move through nanoscale materials than through bulk materials. And the atoms don’t have to travel as far. In addition, nanowires can be bent much further than thicker wires without becoming permanently deformed or breaking.

“A reviewer commented that this is a new important page in the book on mechanics of nanostructures, which was very flattering to hear,” Zhu says. The team plans to explore whether this pronounced anelasticity is common across nanoscale materials and structures. They also want to evaluate how this characteristic may affect other properties, such as electrical conductivity and thermal transport.

The paper, “Large Anelasticity and Associated Energy Dissipation in Single-Crystalline Nanowires,” is published online in the journal Nature Nanotechnology. Lead authors of the paper are Guangming Cheng, a Ph.D. student at NC State, and Chunyang Miao of Brown and Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics. Co-authors include Qingquan Qin, Jing Li and Feng Xu of NC State; and Hamed Haftbaradaran and Huajian Gao of Brown. Gao is a co-corresponding author with Zhu.

The work was done with funding from the National Science Foundation.

-shipman-

Note to Editors: The study abstract follows.

“Large Anelasticity and Associated Energy Dissipation in Single-Crystalline Nanowires”

Authors: Guangming Cheng, Qingquan Qin, Jing Li, Feng Xu, Elizabeth C. Dickey, and Yong Zhu, North Carolina State University; Chunyang Miao, Brown University and Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics; Hamed Haftbaradaran and Huajian Gao, Brown University

Published: July 13, Nature Nanotechnology

DOI: 10.1038/nnano.2015.141

Abstract: Anelastic materials exhibit gradual full recovery of deformation once a load is removed, leading to efficient dissipation of internal mechanical energy. As a consequence, anelastic materials are being investigated for energy damping applications. At macroscopic scale, however, anelaticity is usually very small or negligible, especially in single-crystalline materials. Here we show that single-crystalline ZnO and p-doped Si nanowires (NWs) can exhibit anelastic behaviour that is up to four orders of magnitude larger than the largest anelasticity observed in bulk materials, with a recovery time-scale in the order of minutes. In-situ scanning electron microscope (SEM) tests of individual NWs showed that, upon removal of the bending load and instantaneous recovery of the elastic strain, a significant portion of the total strain gradually recovers with time. We attribute the observed large anelasticity to stress-gradient-induced migration of point defects, as supported by electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) measurements and also by the fact that no anelastic behaviour could be observed under tension. We model this behaviour through a theoretical framework by point defect diffusion under high initial strain gradient and short diffusion distance, expanding the classic Gorsky theory. Finally, we show that ZnO single-crystalline NWs exhibit a damping merit index of 1.13, suggesting crystalline NWs with point defects as potential candidates for efficient energy damping materials.

- Categories: