This is one in a series of five Q&As with the members of NC State’s Leadership in Public Science faculty cluster. Read more about the cluster.

Caren Cooper wrote the book on citizen science. Literally. That made her a natural fit for NC State’s Leadership in Public Science effort.

Cooper is an ecologist whose work involves collaborating with bird lovers to learn more about wildlife and ecosystems in urban, suburban and rural environments. She is assistant head of the biodiversity research lab at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and a research associate professor in NC State’s Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources. She came to Raleigh from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, but it was a bit of a homecoming; Cooper got her undergrad degree at NC State.

As for her book, citizen science is right there in the title: Citizen Science: How Ordinary People Are Changing the Face of Discovery. You can also see Cooper talk about citizen science and its relationship to public science by checking out her TEDx talk online.

Learn about what Cooper is working on.

What does your research focus on?

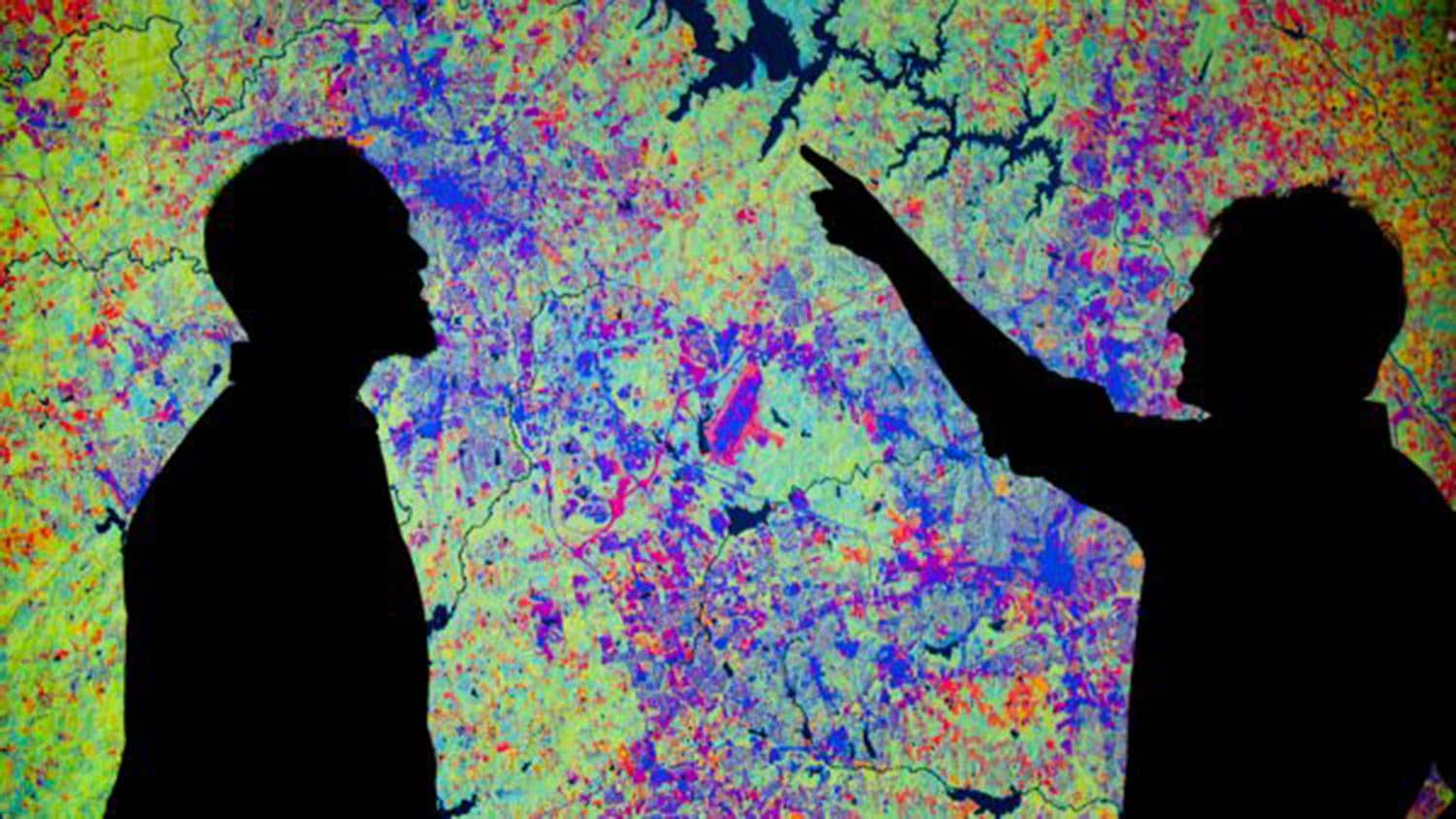

I’m interested in a variety of natural processes and human behaviors related to environmental change. I value and use citizen science approaches to investigate natural-human systems and map environmental changes and disparities. I enjoy exploring the potential of citizen science to manage natural resources and to bring varied hobby groups into citizen science, like birders, nest box monitors, duck hunters, pigeon fanciers, etc.

What does “public science” mean to you, and how does it factor into your work?

To me, public science refers to science that is transparent, out in the open and accessible to all. I think of citizen science as networks of volunteers helping to advance knowledge and public scientists as professionals building and tending those networks and helping people make meaning of the collective information.

I think successful public scientists must be familiar with the teamwork of designing and implementing citizen science, public communication of science in many forms and open science practices from the start of a research project to its completion and again with the next iteration. Citizen science often looks like it is simply people volunteering in service to science, but in a public science context, it is really about bridging the gap between science and society to make sure that science is in service to humanity.

What drew you to public science in the first place?

When I became a scientist, I liked to do all parts of scientific research myself. That’s how I defined being a scientist: someone who can carry out research independently. My husband and I started a family while I was pursing my Ph.D. Field work became difficult, and my priorities shifted.

I was drawn to citizen science at first because it was a way for birdwatchers to collect all the data that I would ever need. Unexpectedly, it also sparked my interest in the social sciences, science communication and open science. I found it puzzling as to why scientists regarded citizen science poorly and typically failed to recognize its many contributions.

At first I was bothered by the lack of acknowledging lay expertise and the efforts and abilities of volunteers. Then I became bothered by the lack of acknowledging the limits of scientific inquiry — there are some big questions that scientists can’t answer by working alone. Citizen science is a social movement among volunteers within science, which I find fascinating and exciting. Public science is a movement among professionals to support citizen science and other forms of public engagement in science, while also supporting the engagement of scientists with the public and in the public sphere.

What sort of public science projects are you working on at NC State?

I’m helping develop SciStarter.com as a central hub for people to find and participate in citizen science projects around the world. We are also designing SciStarter with tools to help projects become more sustainable by sharing resources related to recruitment, retention and communication with volunteer communities. With SciStarter, we will also help advance understanding of the design and outcomes of citizen science.

I run a citizen science project called Sparrow Swap, which partners with volunteers who monitor nest boxes and view house sparrows as a pest species. They collect house sparrow eggs according to one of four protocol options and donate those eggs to the collections at the NC Museum of Natural Sciences, where my lab is based. We use the eggs to study geographic variation in eggshell patterns and color, and to determine whether eggshells can be used as a biological tool for identifying and mapping environmental contaminants. Volunteers also collect data on the effectiveness of different management options, including swapping in egg replicas (which we paint at the museum) for real eggs and hopefully reducing house sparrow reproduction and their disturbance of native nesting birds. We are developing an online interactive guide to the basics of wildlife management principles.

We are soon launching Sound Around Town in partnership with other universities to support soundscape studies led by the National Park Service (NPS). In Sound Around Town, volunteers will be able to borrow sound recording equipment from their local library and deploy the equipment in their backyards to provide soundscape data to the NPS. They will also use our listening app to ground-truth the recordings and provide information on their feelings and perceptions of each type of sound they identify. Though the equipment loans through libraries will be available only in select cities, we hope volunteers across the country will use the listening app in many urban and residential soundscapes. I’m interested in disparities among communities in noise pollution, which is a combination of actual soundscapes and perceptions of sounds.

We are also starting to explore the potential of a citizen science project related to finding feather-degrading bacteria.

As a public science cluster, in collaboration with the libraries, we want to make NC State a citizen science campus in which students campuswide have abundant opportunities to do citizen science as part of their campus life.

- Categories: