Storm Warnings

There’s a comforting sense of timelessness about Brooks Hall – stately home of the College of Design at NC State. Its front portico and columns, encased in Vermont marble, seem to anchor the neoclassical building to an earlier age.

But in his second-floor office in the nearly century-old hall, Andy Fox is racing against time. In collaboration with colleagues inside and outside the university, the landscape architecture professor is working to preserve some of North Carolina’s most prized — and imperiled — rural communities.

“We have so much work to do in eastern North Carolina,” he says, pointing to a map of the coastal plain, crisscrossed by rivers and tributaries flowing in and around hundreds of communities in 41 counties. “It’s a low-lying riverine region that is very susceptible to what’s going on in terms of global climate change and extreme precipitation events.”

Fox and his colleague David Hill, head of the School of Architecture at NC State, raised the alarm in a New York Times opinion piece in October, calling on public officials to abandon the traditional reactive approach to disaster recovery and recognize a new normal.

Despite increasingly frequent and violent Atlantic storms battering the region, “we have learned little about how to respond with long-term fixes and how to help people hardest hit by the storms — not just coastal residents, but impoverished rural Americans in flood-prone areas,” they wrote.

It’s a tangled challenge made more difficult by the confounding interplay of human nature and Mother Nature. “Water, land and people,” Fox says. “No matter where you go in the world, those three things are interrelated, sometimes for good and sometimes not.”

In the watersheds of eastern North Carolina, rivers and streams nourish families and farms tied to an agricultural economy. But when swelled by storms, they threaten communities already struggling to survive.

“We have serious economic, racial and health disparities in eastern North Carolina,” Fox says. “Almost always, the most vulnerable populations are placed in the most vulnerable locations.”

Helping Flood-Prone Communities

Although their work is in its early stages, Fox and Hill – and their colleagues – are already earning awards and recognition for their efforts to help rural, flood-prone communities. The program they co-direct, called the Coastal Dynamics Design Lab, was recently honored with a communications award by the American Society of Landscape Architects for a series of guidebooks they designed to help flood survivors understand the complex information associated with recovery and resilience-building efforts.

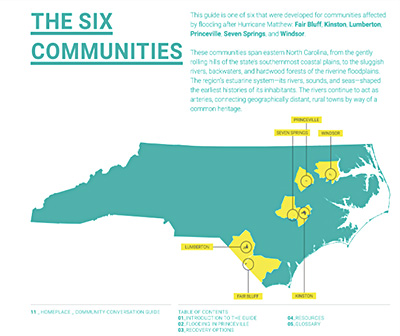

The guides, titled Homeplace, were developed for six North Carolina towns devastated by Hurricane Matthew: Fair Bluff, Seven Springs, Kinston, Lumberton, Windsor and Princeville.

And their work to help historic Princeville, the nation’s first town chartered by freed slaves after the Civil War, gained national attention in November when it was highlighted by the Cultural Landscape Foundation in Landslide 2018: Grounds for Democracy, a report about threatened and at-risk cultural landscapes in the United States.

That work began last fall when the professors joined an interdisciplinary team of university faculty, graduate students, emergency management professionals and public officials for a series of workshops with Princeville residents to help the town craft a path for the future.

Landscape architecture professor Kofi Boone, a co-principal investigator on the Homeplace project, participated in those workshops. He says recovery could take years.

“I’ve only been dealing with disaster recovery for a few years now, but I’ve been amazed at how many resources pour into communities in such a short period of time,” he says. “But then, when you try to turn those resources into tangible benefits, how difficult that process is.”

Resources May Drain Away

Fox says Princeville and other communities ravaged by Matthew are struggling to hold onto resources as state and federal agencies pivot to respond to more recent storms, including hurricanes Florence and Michael.

“Princeville was spared by Florence, but it could see recovery resources drained away now to go to other communities,” he says. “That compounds the disaster.”

It’s just the latest in a long history of misfortune for the town. Princeville, occupying low ground along a bend in the Tar River in rural Edgecombe County, has flooded countless times since its founding. A levee built by the federal government in 1965 offered some protection from the recurrent floods — until back-to-back hurricanes in 1999 submerged much of the town under more than 20 feet of water for 10 days.

In 2016, just six months after the Army Corps of Engineers recommended extending and improving the levee, Hurricane Matthew barreled across the region, leaving Princeville underwater once again.

Despite the challenges, residents are determined to stay and rebuild the community. The town is moving forward with plans to annex an adjacent tract of land on higher ground, recently acquired by the state, where some essential services and housing may be relocated. “That’s a major breakthrough,” Fox says.

But it’s not enough for Princeville to survive. Fox and his NC State colleagues are committed to helping the town thrive economically.

Highlighting History

Boone, an expert in cultural tourism, is working with a community group to create a self-guided walking tour highlighting the area’s historic landmarks. He organized a summer camp for high school students, who walked the tour route and provided ideas and feedback.

“We want to get another generation excited enough about the story of Princeville that they’ll want to come and they’ll want to help with the rebuilding effort,” he says.

The NC State team also created a six-credit-hour design studio for master’s students to build on the ideas identified in last year’s community workshops and to help develop the walking trail concept. Eventually, the professors envision the creation of a heritage corridor with several tours and other economic drivers.

A grant from the North Carolina Community Foundation will help underwrite the design, fabrication and installation of interpretive signage for the tour in the spring.

Long-Term Commitment

Looking forward, Fox sees the work in Princeville as just the first step in the university’s long-term commitment to communities throughout eastern North Carolina — a commitment that’s as durable as the marble columns outside his office.

The College of Design has signaled its willingness to commit more resources to the challenge. The college recently announced that Gavin Smith, an expert in land use and environmental planning who organized the last year’s workshops in Princeville, is joining the Department of Landscape Architecture. He helped coordinate disaster recovery efforts in Mississippi following Hurricane Katrina and in North Carolina following Hurricane Floyd.

Smith, who lost his family home in Houston during Hurricane Ike in 2008, brings a unique perspective to NC State’s work in the field.

“The really exciting and beautiful thing about our profession for me is the different scales at which we can work,” Fox says. “We can work at the site level, at the individual home site, and look at solutions there. But where we’re really at our best is when we zoom out and we look at an entire watershed, and how it’s impacted by the ways that we deal with our environment.”