Saving Princeville

The Princeville, North Carolina, residents gathered at a county administration building last month didn’t need a reminder that their town faces a challenging future as it struggles to recover from the devastation wrought by Hurricane Matthew in 2016.

But nature underscored the point anyway.

On the first day of a five-day workshop aimed at exploring ways of making the low-lying town more resilient in the event of flooding from the nearby Tar River, Hurricane Harvey made landfall on the Texas Gulf Coast. The intended keynote speaker, Administrator Brock Long of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, sent word that he was staying in Washington, D.C., to lead FEMA’s response to the powerful storm.

As the conference was wrapping up on Aug. 29, Hurricane Irma — one of the strongest storms ever recorded in the Atlantic — began its destructive march toward the Caribbean.

“We didn’t plan to hold the workshop between two major hurricanes,” says Andrew Fox, a landscape architecture professor at NC State and one of the organizers of the conference. “The irony wasn’t lost on anyone in the room. But it hardened everyone’s resolve that we need to focus on these issues. These are real events, real people, real lives.”

Undaunted

Resolve is the one thing Princeville isn’t lacking. The historic town, founded by freed African-Americans in the closing days of the Civil War, has weathered more than a few storms in the past 150 years, including the 1887 lynching of a Princeville man by white residents of neighboring Tarboro.

Settled in a floodplain on a bend in the Tar River, Princeville flooded so frequently in its first 80 years that the Army Corps of Engineers built a 2.5-mile dike along the river’s south bank in 1967 to protect the town.

Mayor Ray Matthewson greeted the project with relief and optimism, predicting that the town would “blossom like a rose.”

“It’s fear of the river that has held us back,” he told the Associated Press.

But the river wasn’t done with Princeville. After back-to-back storms in 1999, the town was all but wiped out as the Tar River overflowed the levee, covering homes, schools and businesses with 20 feet of water for 10 days.

Battered but undaunted, the town’s 2,000 residents rebuilt. President Bill Clinton ordered Army engineers to conduct a study aimed at finding ways to protect the town from future floods, “to the extent practicable.” The lengthy report was finalized last April, just six months before Hurricane Matthew barreled across eastern North Carolina, leaving Princeville, once more, underwater.

Even if the report’s recommendations are implemented — enhancing and extending the levee at a cost of $21 million — it will take more than an engineering solution to save Princeville.

Perilous Future

Like many rural communities, the town has seen an exodus of younger residents in recent years to the state’s urban centers such as the Triangle and Triad. That’s fed a cycle of economic and population decline as perilous to its future as any storm.

“The demographics are very challenging,” Fox says. “Because the town has a high percentage of residents over the age of 65, we need buy-in from multiple generations. We need to look at recovery as a long-term effort. It isn’t going to happen in a year or two.”

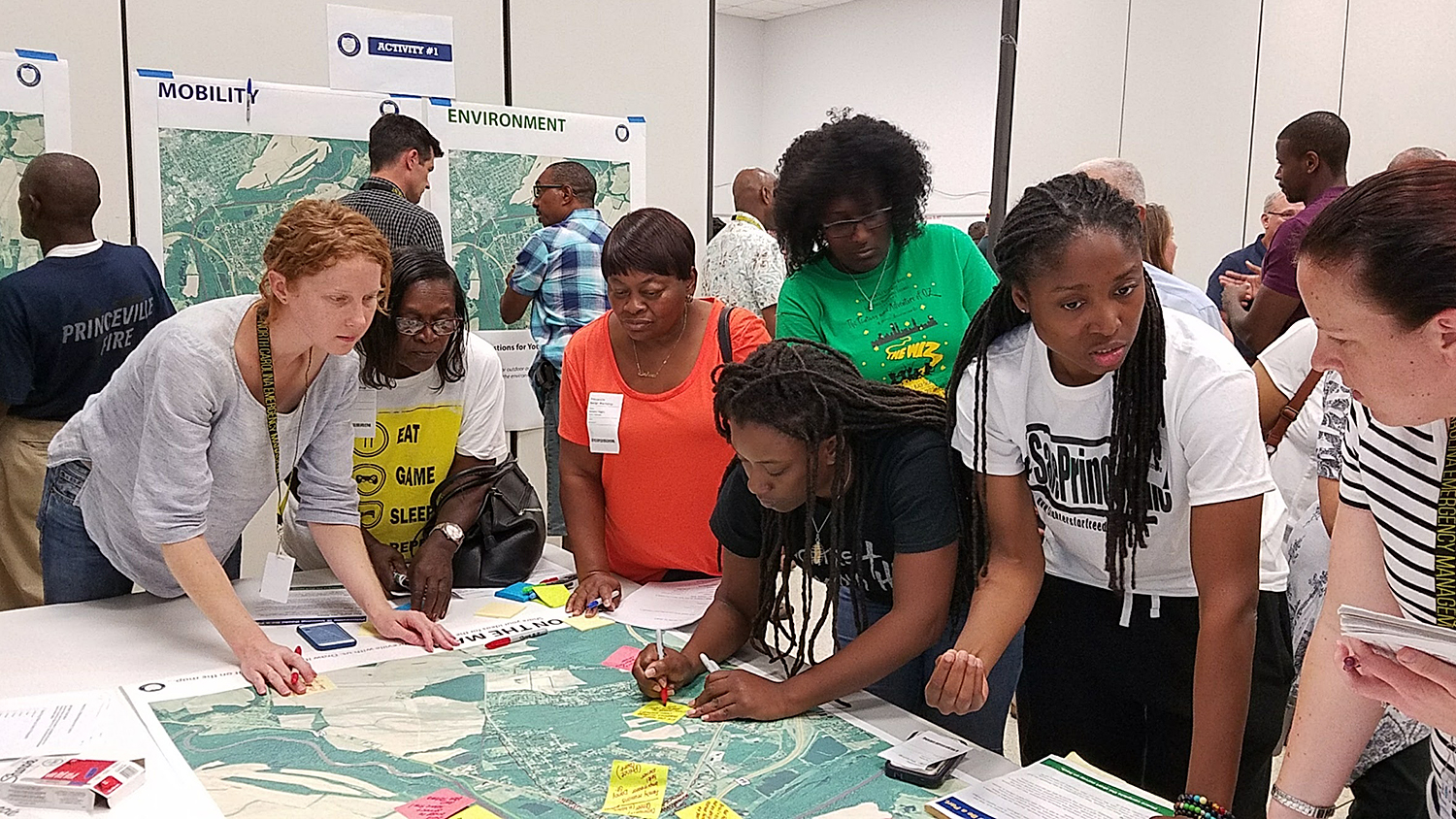

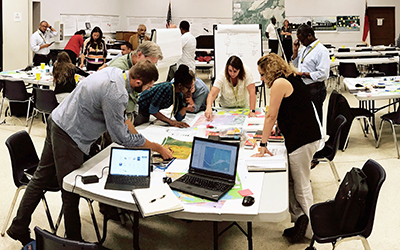

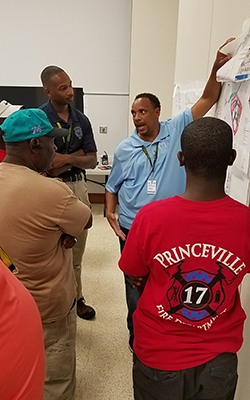

If setting Princeville on a path to growth and prosperity seems like a daunting task, there is no shortage of experts willing to lend their time and skills to the effort. Last month’s workshop, held in the auditorium at the Edgecombe County administration building in Tarboro, brought together university scholars and researchers, state and federal emergency management professionals, land use planners and public officials.

Participants included representatives of the Environmental Protection Agency, National Parks Service, Army Corps of Engineers and FEMA, as well as a host of state agencies, including Emergency Management, Cultural and Natural Resources, Public Safety and the governor’s office.

NC State sent students and professors from the departments of architecture, landscape architecture, and agricultural and resource economics, and from North Carolina Sea Grant. They were joined by researchers from Louisiana State University, East Carolina University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Rolling Up Their Sleeves

“It was exhilarating,” Fox says. “Designers love to roll up their sleeves and just get to work. So it was great having the resources in the room to answer questions about technical issues like environmental policy and land use regulations.”

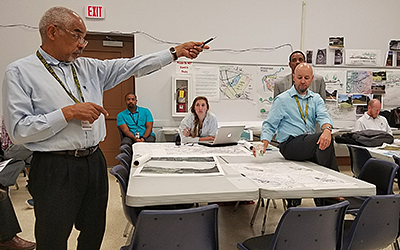

The workshop’s principal organizer, Gavin Smith, is director of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Coastal Resilience Center of Excellence and a professor of city and regional planning at Carolina. Smith, whose family home in Houston was destroyed by Hurricane Ike in 2008, says he wanted more than just technical expertise on display at the workshop.

“It’s important to have technical experts, but I also wanted people who could empathize with the people in the community and involve them in the process,” he says. “I didn’t want us to come in and act like we had all the answers.”

In fact, every evening the planning group invited residents into the auditorium to review their ideas and plans and make suggestions. The following morning, the experts would go back to the drawing board, literally, to refine their plans based on the residents’ feedback.

Send Help

Mayor Pro Tem Linda Joyner says she was surprised and delighted by the way the designers involved the community. “After the flood my continual prayer was, ‘God, send help. Send us people who genuinely have the same heart for Princeville that I have.’”

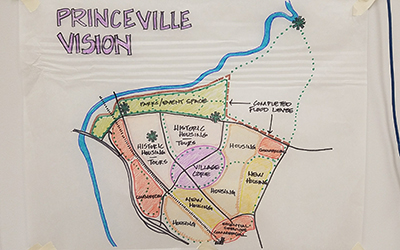

The workshop focused on three broad areas: relocating some residents, businesses and town services to a 52-acre parcel of land outside the floodplain that could be incorporated into the town boundaries; repurposing low-lying land near the river for cultural, historical and recreational uses; and rebuilding some structures in the floodplain to make them more resistant to flooding.

“Essentially, we’re trying to answer the question, ‘How do you take advantage of the opportunity to rebuild the community in a way that doesn’t perpetuate vulnerability but enhances resilience?’” Smith says.

Tourism Opportunities

Kofi Boone, a landscape architecture professor at NC State, sees opportunities to promote tourism by creating a historical trail linking Princeville with Shiloh Landing, a place on the Tar River where enslaved African-Americans were brought by steamboat from Richmond to be offered for sale to Edgecombe County plantation owners. Boone, who developed the pilot project for the African American Music Trails in rural Kinston, North Carolina, says cultural and historical trails often deliver an economic boost to small towns.

“It’s a proven way to allow local people to use what they have in hand — their stories and expert knowledge of a place — to create economic opportunities,” he says.

Joyner, the mayor pro tem, agrees that Princeville’s future is tied to respecting its past.

“Princeville has to stand,” she says, “because of the rich history that it lends to this world. So we need people that believe in us, that believe we can bounce back again, just as our ancestors did, again and again.”

- Categories: