Beer Brewers Abuzz Over Wild Yeast

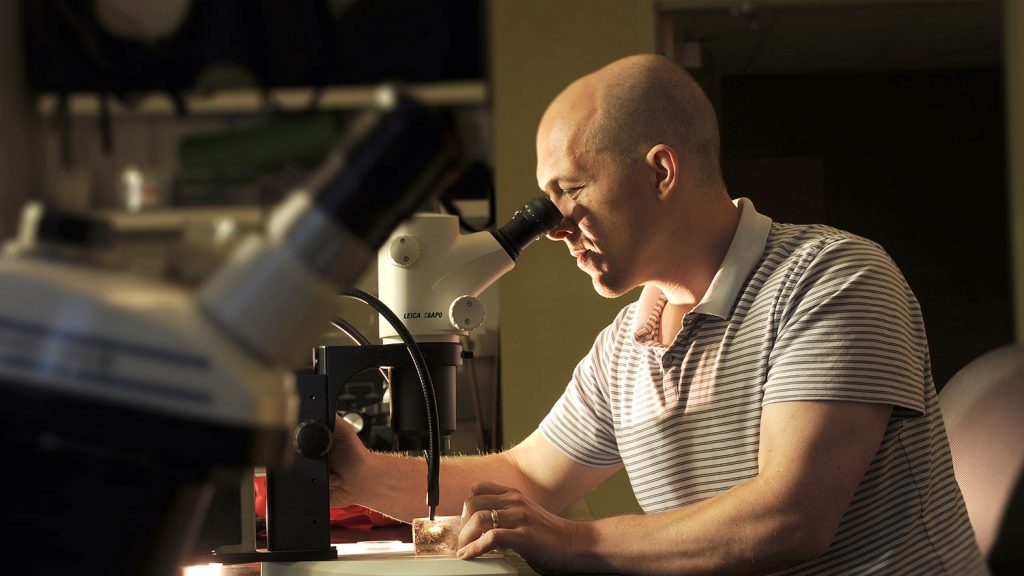

NC State researcher John Sheppard uses wild yeast from bees to brew beer.

When John Sheppard was asked to brew beer from wild yeast, he was skeptical. Humans have been brewing beer for millennia; if yeasts that could make a good pint were out there, they would surely have been found long ago. Sheppard set out to prove himself wrong.

A bioprocessing professor at NC State, Sheppard is both a beer brewer and a scientist. His research focuses on the art and science of turning water, hops, malt and yeast into ales and lagers.

In 2014, representatives of the North Carolina Science Festival approached Sheppard about developing an exhibit on the science of beer for the World Beer Festival, which was being held in Raleigh. They suggested he work with NC State biologist Rob Dunn to find wild yeasts and use them to make beers that could be sampled at the World Beer Festival, offering attendees a tasty and accessible way into the microbial biology of the natural world.

Sheppard’s initial skepticism was well-founded: Of all the hundreds of different species of yeast, many of which include different strains, only two are typically used in making beer. A brewing yeast needs to be able to do two things: it has to “eat” maltose (the sugar in malt) and produce ethanol efficiently. Most yeasts can’t do either, much less both.

But Sheppard was willing to give it a shot. He reached out to Dunn, who reached out to the people in his research group — one of whom, Anne Madden, was a postdoctoral microbiologist and expert on the tiny organisms that live on insects.

Because of her background, Madden knew that paper wasps are home to communities of yeasts, some of which are associated with winemaking. By taking samples from the wasps, she ultimately isolated a wild species of yeast that had never been used for commercial brewing. She shared it with Sheppard, who cultured the yeast and brewed with it.

The results were not what he expected.

“That first batch produced a really sour beer,” Sheppard says. “But when we served it at the World Beer Festival, people loved it.” And, since people loved it, the researchers did it again.

What they had found was amazing. By making small adjustments to the brewing process, the wild yeasts produced very different flavor compounds, called esters. Some of the ales tasted like sour beers, some like honey, some like apple cider. And these characteristics could be extremely useful for brewers.

Some of the ales tasted like sour beers, some like honey, some like apple cider.

Once they realized the potential of these wild yeasts, the researchers began collecting data on how these yeasts grow and precisely which esters they produce. They also worked with NC State to file an invention disclosure to protect their intellectual property and secured financial support from the Chancellor’s Innovation Fund, which helps researchers move innovative concepts from the laboratory to the marketplace.

“We want to see how many of these [yeast] strains we can find,” Dunn says. “Are tens of new and useful strains lurking out there? Hundreds? Thousands? We’ll be figuring out the best ways to get these new strains to the folks who can use them.”

The science behind the brew

In his research with Dunn, Sheppard focuses on finding innovative ways to brew beer. But he spends most of his time teaching students the fundamentals in a place most people don’t know exists: the brewing lab in the basement of Schaub Hall.

“The academic side of brewing is interesting because it’s a good example of how science and process engineering come together,” Sheppard says. “Brewing was one of the first biotechnological processes, meaning it uses living cells to make a higher-value product.”

Sheppard, a faculty member in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, says it’s the interaction between science and the practical aspects of making an improved product that is attractive to his students.

“It’s a really hands-on activity. The students get right in there stirring the grain and the mash and hooking up hoses and pumps,” he says. “It’s a lot different than sitting at a desk.”

It’s a

really hands-on activity. The students get right in there stirring the grain and the mash and hooking up hoses and pumps. It’s a lot different than sitting at a desk.

The brewing lab produces five year-round beers: Pack Pilsner, Chancellor’s Choice IPA, Brickyard Red, Ma Blonde D’or (Golden Blonde) and Schaub Schwarzbier. It offers four seasonal brews, too: Wolf-toberfest in the fall, Pullen Porter in winter, Graduator Maibock in spring and Wolfpack Wheat in summer.

For now, those beers are available only at events on campus, although Sheppard said the brewery recently got a license that will eventually allow them to be sold at the Lonnie Poole Golf Course, the University Club and other public-facing places on campus.

Wherever its beer may end up, the brewing lab’s focus will stay on teaching the science of beer and preparing the workforce for the state’s burgeoning beer industry. But the skills learned in the lab have broad application, said Claire Svendsen, a master’s student in food science.

“We’re studying a yeast that was isolated here and appears to be unique in its own right. It’s interesting that we’re still finding undiscovered organisms with different characteristics,” she says. “We can use them to make foods, other drugs, metabolites we might purify. There are a lot of avenues you can go with it.”