Taking Care of the Pack in a Pandemic

Student Health Services leads the way in keeping the Wolfpack healthy — especially when a novel pathogen turns life upside down.

Running a full-spectrum student health operation at North Carolina’s largest university would be a tall order under the best of circumstances. But in the midst of a pandemic?

“We’ve had to pivot on a dime over and over again,” says Jenn Wilder, associate director of Student Health Services at NC State. “You come in with a plan in the morning, and by five o’clock that plan has changed.”

Change has been the only constant ever since campus restricted operations in March of this year, says Dr. Julie Casani, director and medical director of SHS.

“Initially we thought that when students came back from spring break, we’d see this onslaught of people who were sick,” Casani says. “We made a bunch of contingency plans for that eventuality. But the decision was made not to bring the students back, so we asked ourselves: What do we do now?”

SHS responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by devising new ways to fulfill their core mission, which is to meet students’ health care needs in areas including primary care, gynecology, physical therapy, nutrition counseling and pharmacy. Through partnerships with local clinics, Student Health also provides on-campus access to orthopaedists, gastroenterologists and dentists. But how do you provide services to students who aren’t there?

In a word — telehealth.

“We had to acquire the technology and develop the expertise and the systems to deliver care through a telehealth model,” Casani says. “The staff did a phenomenal job, and within six weeks, we had a fully functioning telehealth program.”

Telehealth is well-suited for a variety of health care needs, such as follow-ups, consultations and prescription refills. Students can call SHS to make telehealth appointments. The sessions take place via a Zoom call that complies with HIPAA standards for privacy and security. The telehealth program has been a great success, and students have reported high satisfaction with it, so SHS plans to continue providing telehealth services after the pandemic ends.

Once SHS got established providing services remotely, the unit’s health care providers — a group including physicians, physician assistants, nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, physical therapists and nutritionists — spent the summer collaborating with administrators to plan for the return of students in the fall. They also figured out how to safely provide services to the relatively few students who remained on campus in the spring and summer.

“We stopped taking walk-in appointments, but we do see students in person by appointment, six days a week,” Wilder says.

Providers who meet with students who have possible symptoms of COVID-19 wear full personal protective equipment — an isolation gown, gloves, an N95 face mask and a face shield — for the duration of the appointment.

“Our volume isn’t high, but we do see sick people, and we have seen COVID patients,” says Casani. Fortunately, thanks to the precautions they’re taking, no SHS staff have tested positive for COVID-19 at any time since the beginning of the pandemic.

“Our staff are all exposed to some degree of risk, but they’re here because they love students,” Casani says. “They’re champions. Their morale is incredible.”

Perhaps one of the reasons SHS staff morale is so high is that they genuinely love their jobs. At least that’s what drives Lisa Dolan, SHS medical laboratory supervisor.

“I’ve been with NC State and Student Health since 1989, and I still feel like I don’t want to leave,” Dolan says. “I love my co-workers — we have a very warm and welcoming environment here — but the students are the best. They usually don’t like to come to the lab because we stick needles in them to take blood,” she says with a grin, “but we do our best to calm those fears.”

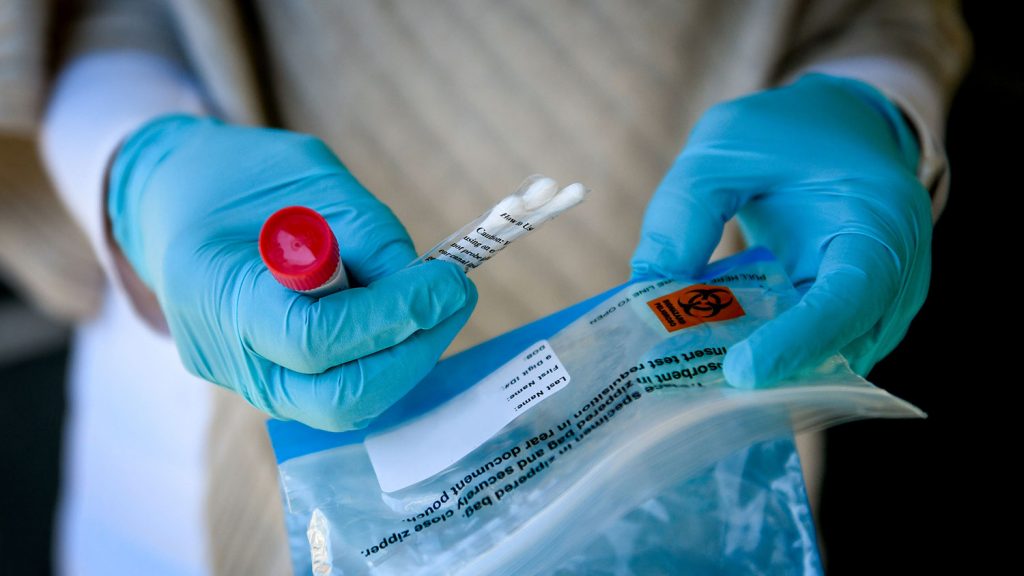

Dolan’s staff of lab and X-ray technicians perform the diagnostic tests that providers rely on to make their diagnoses. They also manage the collection of specimens for COVID-19 tests. At the beginning of the pandemic, SHS was only testing symptomatic students and people contacted through the contact tracing program. Now SHS has expanded its testing capacity so that any student can be tested at no cost, with or without symptoms.

The specimens are collected at multiple locations around campus, including a large white tent behind the SHS building on main campus. Patients collect their own specimens by inserting a swab into their nostril — “but it’s not the one that goes way up into your brain,” Dolan hastens to add. This less-invasive swab is rotated around each nostril three times, and then the swab is sent to an outside lab for testing.

SHS is currently processing 350-500 tests a week, with the results available in 24-72 hours. Although this is a quick turnaround, they hope to speed it up far more by bringing more COVID-19 testing in-house in the spring. That’ll reduce turnaround time to one hour — if they can make it happen.

“First you’ve got to buy the equipment to do the testing,” Dolan explains, “but that’s only the beginning. You can’t do the tests if you don’t have all the other things you need: swabs, PPE, viral media, test kits. That’s been the real challenge. It’s all about supply and demand. If the suppliers don’t have it, we can’t get it. Sometimes even nitrile gloves are hard to keep in stock.”

In-house testing with one-hour results will make it much easier to control the spread of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, but a negative test result doesn’t give you a shield against turning positive afterward, Casani warns.

“Students call me on Thursday and Friday wanting to get tested because they think a negative test means they can go out and party that weekend,” she says. “That’s incorrect. There’s a famous epidemiologist who said, ‘We can’t test our way out of this.’ That’s because this is a communicable disease, which means we have to prevent exposure; but the test is a postexposure event, not a prevention event.”

Preventing the spread of COVID-19 requires multiple layers of intervention, Casani says. When students were brought back to campus in August, they returned to a campus environment where many of those layers had been put into place: frequent cleaning and disinfecting of high-touch surfaces, copious availability of hand sanitizer, signage regulating traffic flow within buildings, more classes offered online, and most important of all, new community standards requiring physical distancing and the wearing of face coverings.

“We did great in the classrooms,” Casani says. “There have been no documented cases of within-classroom or classroom-to-classroom transmission of the coronavirus on campus.” However, soon after students returned, many clusters of positive cases were identified, mostly in off-campus and Greek housing. That led to a steep reduction in students living on campus, to stop the spread of the disease.

“We did OK in the residence halls,” Casani says, “but now that we’ve analyzed the data we’ve learned that single-room occupancy is important. Low density of people in suites is important. Socializing is a major risk factor if not done safely.”

For instance, even when you’re outdoors playing sports, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be wearing a mask. If you can’t guarantee you’re 6 feet apart, wear a mask, Casani says.

“The students need to think about how they’re socializing, and we need to give them avenues to socialize safely,” she says.

Those avenues are being discussed right now, as Casani, Chancellor Randy Woodson, Provost Warwick Arden, and other campus leaders are formulating plans for the safe return of many students to campus in the spring semester.

Wilder, for one, is looking forward to having more students back on campus.

“I’m excited to feel the energy that students can bring, to have a more open building, to have students around,” she says. “That’s part of the reason why this position was so appealing to me. Undergrads keep you young, so I’m excited about staying young as long as possible!”