People, Plants and Pride: The Passions of J.C. Raulston

A quarter-century after his death, the founder of NC State's arboretum is remembered for his pioneering efforts to cultivate a welcoming space for LGBTQ professionals in horticulture.

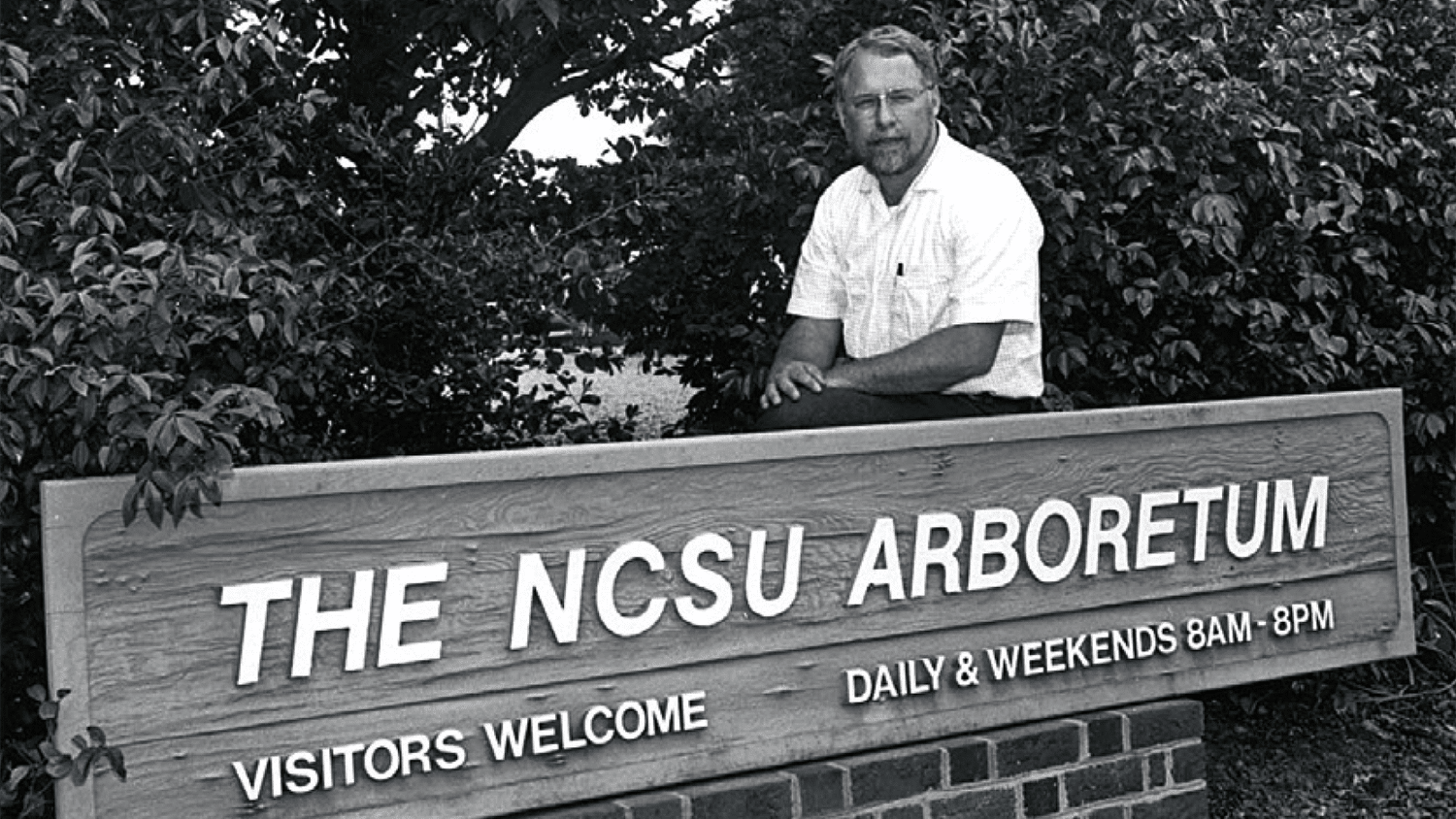

At his untimely death in 1996, J.C. Raulston was hailed for his role in introducing new varieties of plants to the American landscape. The founder of the NC State arboretum that now bears his name was killed instantly in a head-on collision along a rural stretch of U.S. Highway 64 near Asheboro, North Carolina, just days before Christmas.

A Christmas Eve obituary in The New York Times lauded Raulston as “a generous-spirited giant among horticulturists.”

Peter Del Tredici, a research scientist at the Arnold Arboretum at Harvard University, called Raulston “a selfless advocate for broadening and improving the selection of horticultural plants,” noting that he “distributed quite literally millions of cuttings and seedlings to the nursery industry and botanic gardens.”

But the 56-year-old Raulston cultivated more than plants. For the last two decades of his life, the professor of horticulture nurtured a network of LGBTQ people connected by their love of plants as much as their sexual orientation.

For all Raulston did to advance horticulture, says his biographer, Bobby Ward, “his greatest contribution may have been the connections made among gay and lesbian gardeners in the comfortable network he created through the Lavandula and Labiatae Society.”

Raulston organized the society in 1978 during the annual conference of the American Society for Horticultural Science in Boston. By 1990 it had nearly 300 members in 34 states. The society’s name comes from the Latin words for two types of plants — lavender and mint, respectively.

Ward, who earned both a master’s degree and a doctorate in botany and plant physiology at NC State, often attended meetings at Raulston’s home in downtown Raleigh. He says the society connected Raulston’s personal and professional lives and offered a safe place for gays and lesbians to socialize in a less welcoming era.

A Whole New World

“When he came out and had his first [gay] experience in 1975 at age of 35, it was a whole new world for him,” Ward says. “You have to look back at what life and the world was like then. He had to walk a very careful tightrope of being out to those he could trust but not out to people that he didn’t think would be accepting of it.”

Among friends — and in his writings for LGBTQ professionals and associates in the industry — Raulston was remarkably frank about his personal life. In a 1983 letter to friends, preserved with his papers in the special collections of the NC State University Libraries, Raulston confided that he was having a hard time coming to terms with a failed relationship.

“In 1980 I met my dream man encompassing everything I could ever want in a man and fell deeply in love — with fantasies of rose-covered cottages and a life of travel and work together. But it ended a year later as he unexpectedly and suddenly left me,” he wrote. “I’ve felt I’ve finally accepted and got over it OK — but at the same time I realize I haven’t dated or gotten close emotionally to anyone since — so perhaps the scars are still healing.”

Still, Raulston traveled widely and found time to take in a wide variety of LGBTQ social and political events. In the early 1980s he attended pride parades in New York, San Francisco and the District of Columbia; the Southeast Gay Conference in Memphis; the Gay Rodeo in Las Vegas; and the Castro Street Fair in San Francisco. And he vacationed at gay and lesbian resorts in Provincetown, Massachusetts; Fire Island, New York; and the Russian River area of Northern California.

He spent a 1981 sabbatical in San Francisco, home to one of the world’s most vibrant and active queer communities, enjoying the freewheeling atmosphere that prevailed before the AIDS epidemic.

“There is a special electricity in workouts in an all-gay gym on Castro [Street] featuring the most beautiful men of the city — good for muscles but terrible eye strain,” he wrote to friends after returning to Raleigh. “But there is another side to the glitter of S.F. that lures so many from across the U.S. Although there is so much to participate in and so many incredible men to look at — it seems to me that friendships and relationships are probably more difficult to develop there than anywhere.”

In a brutally honest critique of the city’s gay scene, then largely centered around bars and bathhouses, Raulston told his friends, “Sex was easy — human contact seemed virtually impossible.”

Out of ‘The Green Closet’

Through the Lavandula and Labiatae Society, Raulston created a healthy alternative to the bars and baths — a place where gays and lesbians in horticulture could connect, without compartmentalizing their lives or leaving their identity at the door. He organized meetings and events on the margins of major industry conferences, and hosted regular get-togethers for members in the Triangle.

In 1985 he organized a three-day event called Gardensocialfest, which included visits to the NC State arboretum; the Ava Gardner Museum, then at its original location in Brogden, North Carolina; and the WRAL-TV gardens in Raleigh; as well as a potluck dinner at the Little River Farm nursery in Middlesex, North Carolina.

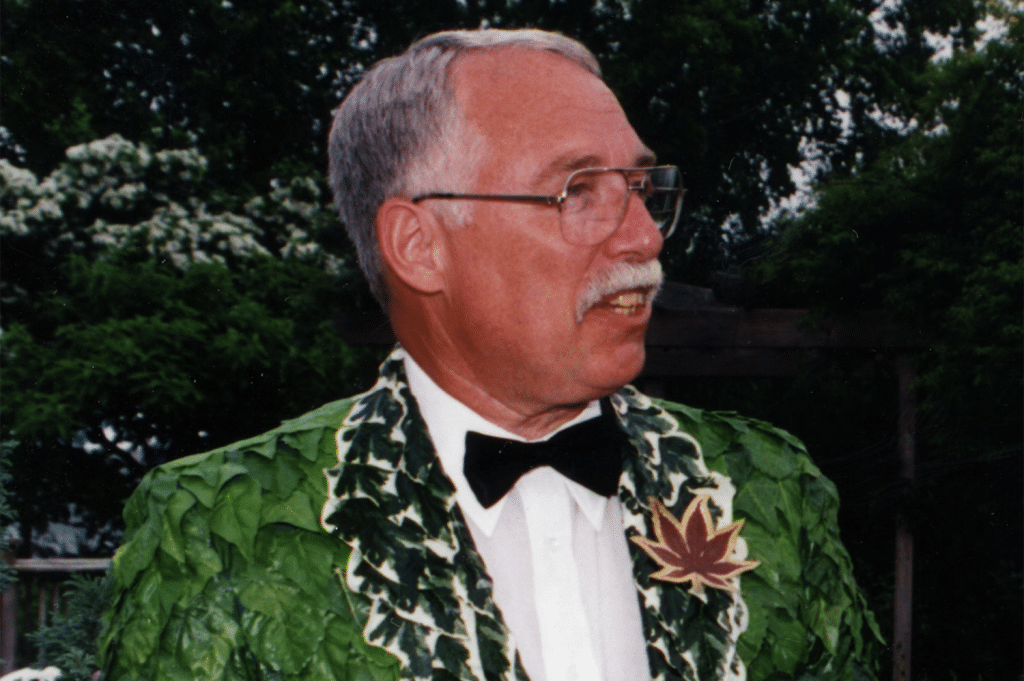

Occasionally Raulston would treat members of the society to a presentation titled “The Green Closet,” a collection of slides that highlighted gay and lesbian gardeners of note. According to his biographer, Ward, “This lighthearted slide lecture also included bawdy images from Greek pottery and nude Italian sculptures, as well as photos of scantily clad landscapers and gardeners, covers of male physique magazines, and ‘plant pornography’ (such as Amorphophallus, cactus, and plant fruits that were suggestive of male and female human anatomy).”

Raulston found love again in the summer 1986 when he met a Canadian man, David Sayer, during a trip to Vancouver, British Columbia, to attend the Expo ’86 World’s Fair. By the fall of that year, the two men were living together in a small house near the NC State campus while they renovated an abandoned warehouse in downtown Raleigh.

Tragically, Sayer died of complications of AIDS on May 5, 1990, at the age of 34.

A Horticultural Hub

After Sayer’s death, Raulston took comfort in opening the 4,000 square foot home on Davie Street to friends and colleagues, including members of the Lavandula and Labiatae Society. “It was an extraordinary house and unique design,” Ward says. “The house afforded great occasions for entertaining, organizing arboretum fundraising parties, hosting overnight guests from around the world, and allowing students to connect outside the classroom with noted horticulturists, opportunities few other NC State horticultural faculty members provided.”

In researching his biography of Raulston, Chlorophyll in His Veins, Ward talked to former students and colleagues who recalled the annual ritual of decorating the home’s giant Christmas tree with unusual and sometimes outrageous ornaments that Raulston had collected on his travels around the world.

“The house became so well known that many people thought of it as a horticultural hub,” Ward says.

Raulston Remembered

Thankfully, in the years since his death, Raulston’s contributions to NC State and to horticultural science have not been forgotten. A 2016 exhibit in the D. H. Hill Jr. Library gallery celebrated Raulston’s life and work, from his childhood in Oklahoma to his two decades of service to the university as an educator, horticulturist and arboretum director.

The exhibit, designed by Molly Renda, included a panel on Raulston’s founding of the Lavandula and Labiatae Society and his efforts to support LGBTQ professionals in horticulture.

Renda says she felt a strong connection to Raulston while working on the exhibit, even wearing his glasses one day after discovering that she had left her own at home. “They were my prescription. That sort of underscores how deeply I felt like I was getting to know this person.”

It was a gesture Raulston might have appreciated.

Ward says Raulston’s giving nature was legendary. When landscape designer Rick Darke admired the new dark blue NC State arboretum sweatshirt that Raulston was wearing on an outing to the Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, “J.C. took it off right there and gave it to Darke.”

In a changing landscape, Raulston’s passion for his work and his spirit of generosity live on — in the work of the JC Raulston Arboretum, in the lives and contributions of his former students and colleagues, and in a more welcoming environment for LGBTQ people at NC State and beyond.

The New York Times summed up Raulston’s legacy in his 1996 obituary this way: He “leaves no survivors — except for his hundreds of friends, and millions of plants.”

Raulston penned a shorter version, ending many of his letters by urging readers to take up his cause: “Plan and plant for a better world.”

- Categories: