A History of Women’s Success

Fifty years ago, Title IX began leveling the playing field for women and men in college athletics. At NC State, women student-athletes and their coaches seized the opportunity and never looked back.

In the span of two weeks, women’s team athletics at NC State was off and running, like an undefended fast break.

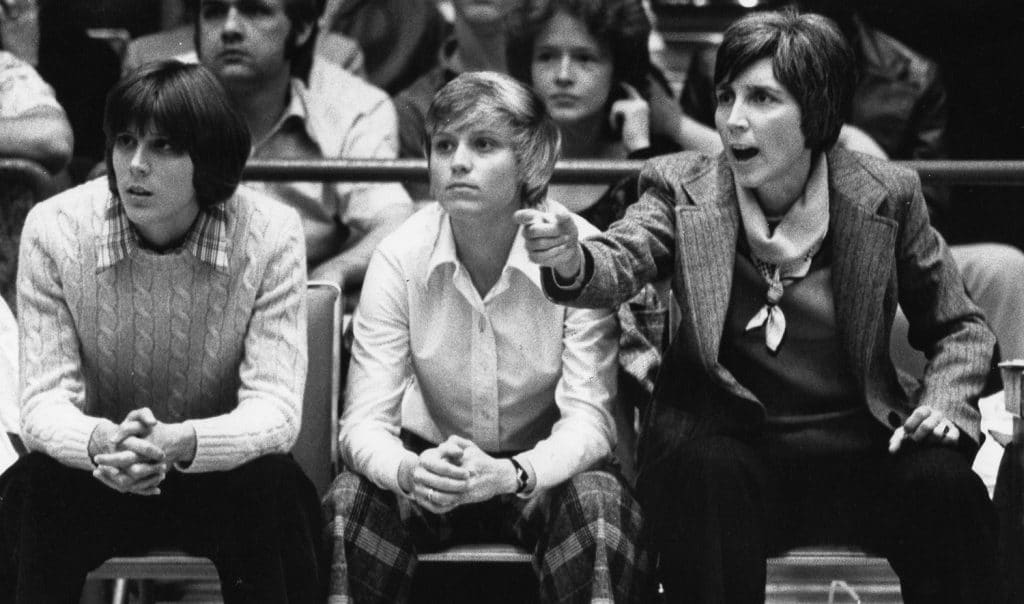

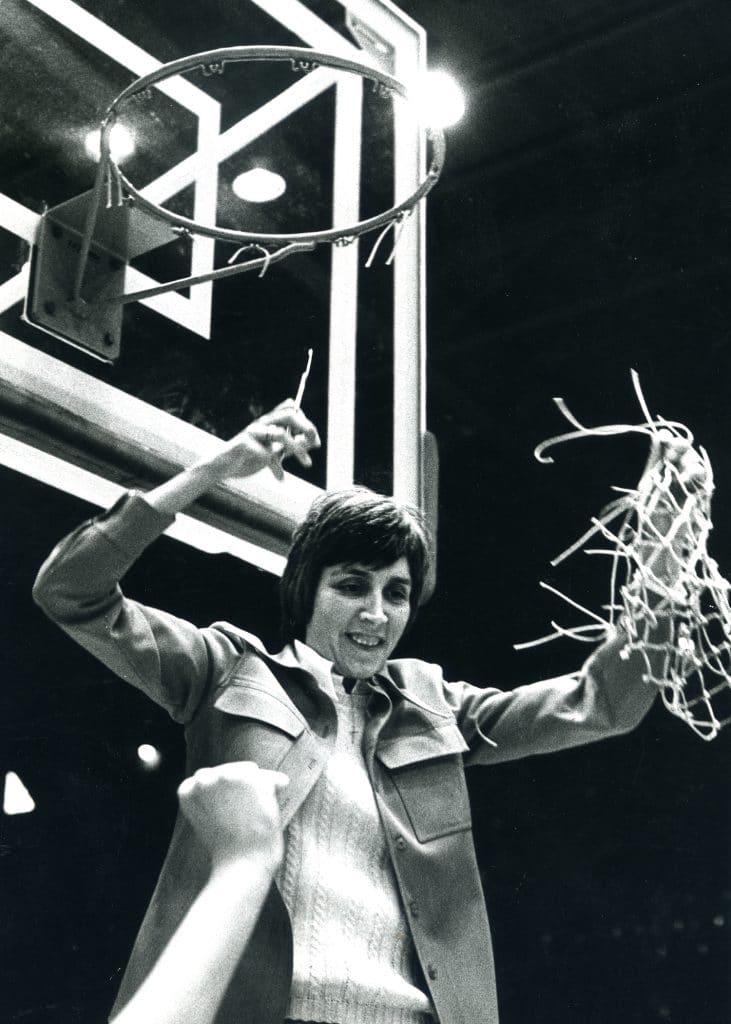

It happened in 1976 in a pair of basketball games played at Reynolds Coliseum, one that went statewide and one that was international, under the guidance of newly hired coach Kay Yow, who turned her lifelong passion for sports into a hall of fame career in more than three decades at NC State.

The first was a game between timeless rivals, NC State and North Carolina, a contest so anticipated between the Consolidated System schools that UNC Television chose to broadcast it to its network of public television stations across the state.

The next was an exhibition game against the touring China Air Lines Team from Taiwan, who wanted badly to play in Reynolds Coliseum because it was the home of men’s international superstar and three-time ACC Player of the Year David Thompson. The Chinese team came in undefeated but lost 71-70 to the Wolfpack in front of more than 3,000 highly engaged spectators.

Those two victories, coached by Kay Yow and starring her younger sister Susan Yow, created an interest in women’s athletics that still burns intensely today for a department that has the reigning NCAA Champions in women’s cross country and an unprecedented three-time ACC-champion women’s basketball team.

In nearly a half century since then, NC State’s allegiance to and support of women’s athletics has enriched the experience of all who support equal access and opportunities on campus, from providing nearly 150 scholarship opportunities to adding a female mascot presence to games, campus events and private gatherings.

It all happened, of course, because of Title IX of the Educational Amendments of 1972, the landmark legislation signed into law by President Richard M. Nixon on June 23, 1972, preventing all forms of sex discrimination at any school receiving federal financial assistance.

NC State had been the ACC’s leader in ending athletic segregation in 1956 when it accepted its first four Black undergraduates, with three of them participating in varsity athletics at some point during their student careers. In 1960, Durham’s Irwin Holmes became the South’s first captain of a varsity team and NC State’s first Black graduate.

The institution’s first full-time female student enrolled in 1921, but the school wasn’t fully coeducational for another 40 years. Several individual varsity athletes competed for the Wolfpack as women’s enrollment increased, especially after 1964, when the institution issued its first “Report on the Status of Women Students” and opened Watauga Residence Hall as the first on-campus housing for its small female population. All enrolled single women were required to live there.

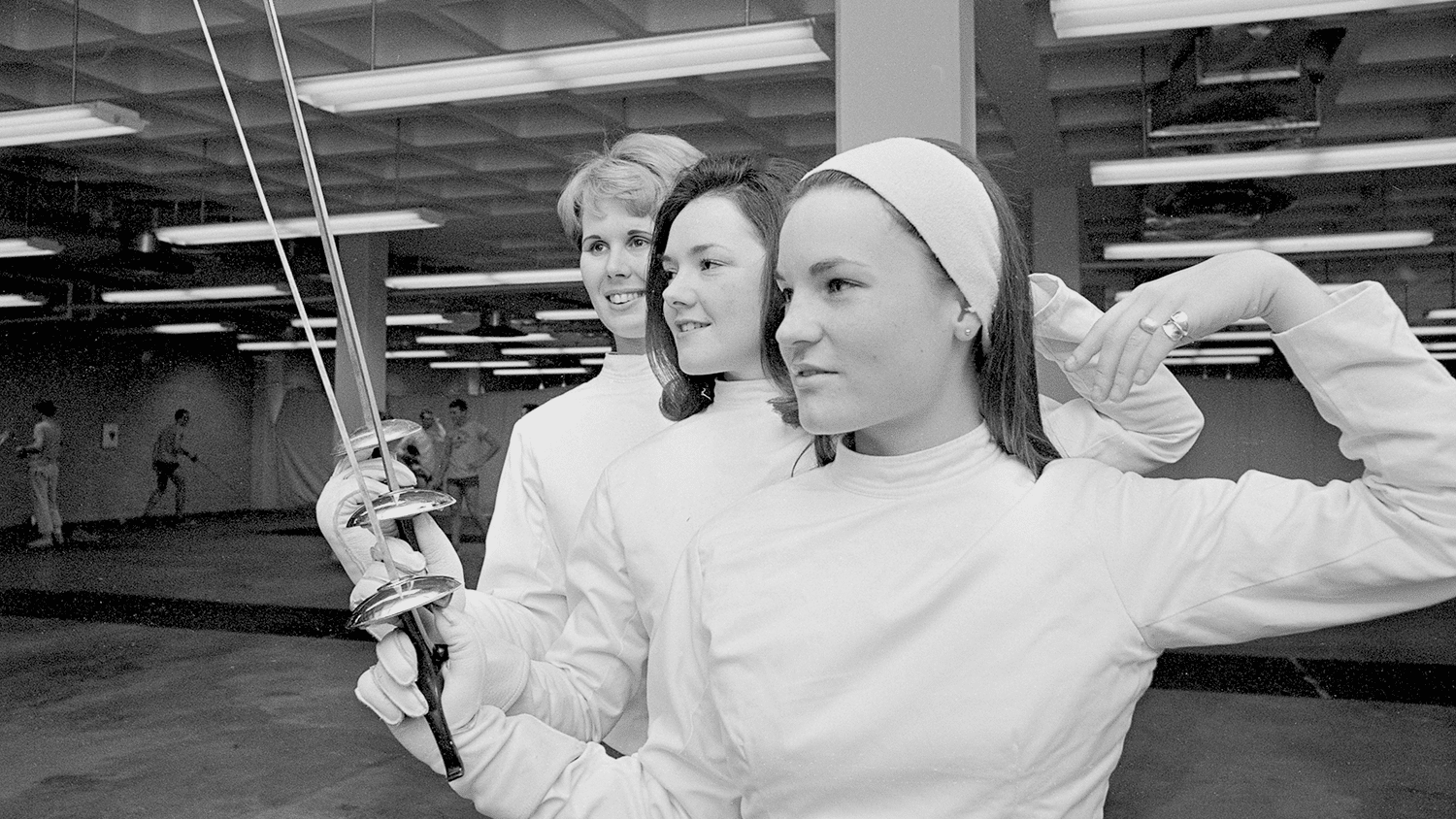

In 1965, two women joined the varsity coeducational rifle team, and one varsity cheerleader joined the fencing squad.

It wasn’t until nearly a decade later that the school first sponsored women’s-only varsity teams, when Athletics Director Willis Casey hired Robert “Peanut” Doak as an interim women’s basketball coach while he looked for an appropriate full-time women’s coach and administrator. At the time, NC State’s undergraduate enrollment included 11,656 men and 4,093 women.

Importantly, those earliest women’s teams were fully integrated and have been ever since.

Casey, known for his financial frugality and his fierce competitive streak, didn’t want to just sponsor women’s athletics, he wanted the Wolfpack to be among the nation’s elite in every sport.

The Beginnings of Women’s Athletics

Diane Ramsey, who graduated from the School of Natural Resources with a degree in parks and recreation administration in 1967, didn’t benefit from the passage of Title IX as a student-athlete. She did, however, use it professionally to create scores of recreational programs for girls in Harford County, Maryland, where she was a recreation director for 35 years.

The Raleigh native joined the cheerleading squad at State shortly after graduating from Needham Broughton High School in 1963, only because she was looking for an activity to keep her on campus during the day, since she lived at home with her parents and not on campus.

While taking an introductory physical education class under fencing coach Ron Weaver, she accepted his offer to join the varsity program, which at the time was all male. Weaver, a native of Ohio, was an accomplished fencer who came within one touch of winning a spot on the United States fencing team that participated in the 1960 Rome Olympics. He wanted to expand the sport he loved, both on campus and throughout the state.

Ramsey was a quick learner, and before long she won local and state competitions, as did the individual fencers that followed her, including Karen Costarisan and Cathey Jehle in 1967 and Barbara Walters, Gladys Mason and Barbara Grice in 1969. Weaver created enough interest in his sport for NC State to host the 1969 NCAA Fencing Championships at Reynolds Coliseum.

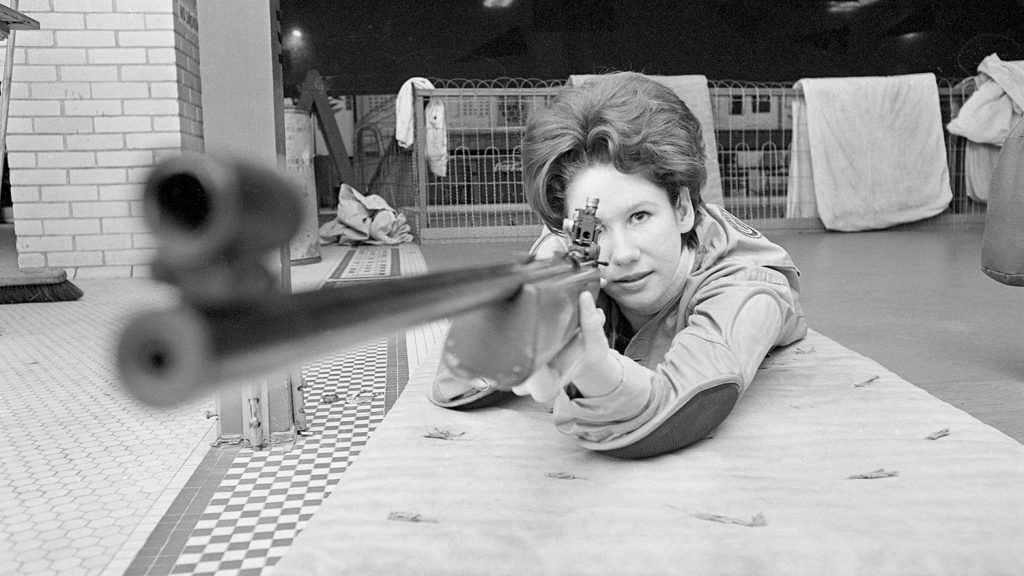

Meanwhile, in the fall of 1965, both Alma Williams of Covington, Virginia, and Pam Lias of High Point tried out for and earned spots on the Wolfpack rifle team, while nationally recognized swimmer Susie Resseguie practiced with, but could not compete for, Casey’s varsity swim team.

When the ACC was formed in 1953, there were no considerations for women’s athletics, though Virginia’s Mary Slaughter played for two seasons on the Cavalier men’s tennis team before transferring to UNC-Greensboro. When Olympic-caliber swimmer Mary Brundage tried to do the same thing in 1965, the league made a specific ruling that women couldn’t compete in athletics because its bylaws specifically used the word “he” in referring to student-athletes.

Ramsey, now 77 and retired in Annapolis, Maryland, fondly remembers her time as a student-athlete at NC State.

“We trained together and worked together,” she says. “Women were only allowed to compete in the foil—not the sabre or epee—so I only had to learn one discipline. I knew some of the men on the team from high school.

“I don’t feel like I experienced any particular discrimination, there just weren’t many of us who were on the varsity teams. I loved my time on the team, being able to get out and be with my peers.”

Ramsey wanted to make sure she created similar chances when she entered the professional world. When she first went to Maryland, the only recreational activities offered to young girls were ballet and baton twirling and anyone interested in other sports had difficulty finding facilities to practice or play.

“Having Title IX made a huge difference,” Ramsey says. “We literally couldn’t schedule any facilities. The men’s and boys’ teams took up all the prime-time slots. All we wanted to do was get some reasonable times for the girls to have games and practice.

NC State’s First Women’s Teams

While Title IX gave more opportunities for women who wanted to compete in athletics, the earliest programs were hardly on the same footing as the established men’s programs.

For starters, those teams were governed, not by the NCAA, but by the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW), which had some odd rules and ideas for women’s sports as they tried to maintain a purity over the men’s sports they thought—back then—were overly commercial, dependent on making money and rife with recruiting discrepancies.

Mainly, the AIAW was made of women’s coaches and physical education instructors who thought they could keep those issues at bay. The AIAW did not allow off-campus recruiting and schools could not pay for recruits to visit campus. There were no athletic scholarships for women, at least in the first year. There were two divisions of competition, Class A and Class B.

Having Title IX made a huge difference.

After every game, players from both teams were required to meet in a designated room for cookies and drinks, in an effort to foment collegiality.

Teams often traveled by station wagon, carried boxed lunches from the dining hall for the road, stayed in opposing team dorms and were required to make their beds before they played. With little money set aside for uniforms, players often had to purchase blank jerseys from local sporting goods stores and iron their own numbers on in their dorm rooms.

“When you start comparing what it was like back then to today—oh, my goodness,” says NC State Athletics Director Emeritus Debbie Yow, the first female athletics director in ACC history when she was hired at Maryland. “You can’t even explain it.”

Few women’s coaches had full-time positions. They were often required to teach physical education classes and handle all athletics administrative duties. When Kay Yow was hired from Elon in the summer of 1974, she took over the women’s basketball team and added volleyball and slow-pitch softball.

“And you know what?” her sister says. “We didn’t care. The reason we didn’t care is we got to play. How many people understand when you are forbidden to do something and you have no opportunity to do what love then you get to do it?

“It was amazing.”

NC State was successful in the AIAW, winning back-to-back cross country championships in 1979 and ’80, with teams like basketball garnering national attention under Kay Yow’s leadership as she was on her way to winning more than 700 games, four ACC titles, a berth in the 1998 Final Four and a coveted spot in the Naismith Memorial Hall of Fame, where she is enshrined with two NC State men’s basketball pioneers, coach Everett Case and player David Thompson.

By the early 1980s, however, the AIAW way of thinking was completely outdated and college athletics for women was growing exponentially around the country.

NC State became influential as women’s athletics transitioned to NCAA governance in 1981. Wolfpack long distance runner Betty Springs won the first ever NCAA-sponsored women’s event at the national cross country championship and Nora Lynn Finch, an assistant coach to Kay Yow who eventually became the first full-time athletics administrator at an ACC school, was the first chair of the NCAA Women’s Basketball Tournament in 1982. Finch joined Kay Yow in the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in 2019.

The reason we didn’t care is we got to play.

Today, NC State sponsors more than a dozen women’s sports, all fully funded with the maximum number of scholarships allowed by the NCAA. That includes 72 student-athletes on full scholarship and an additional 76 sharing the equivalent of 42.6 scholarships. The athletics department spends $16 million on women’s athletics operations and $6.6 million on scholarships.

There are still advances to be made, as the NCAA discovered last year as some women’s teams found their facilities and work-out centers for the COVID-affected NCAA basketball tournaments to be lacking. The NCAA ordered multiple studies to address the inequities.

More Than Athletics

The key to Title IX’s success on every campus is that it provides more than equality in athletics. In fact, says NC State Vice Provost for Institutional Equity and Diversity and University Title IX Coordinator Sheri Schwab, athletics is just one part of the landmark legislation that also monitors and addresses sexual harassment, assault and misconduct, along with support to advance other campus initiatives such as the Women’s Center, which is now celebrating its 30th year on campus. For a land-grant institution that was once a military training center with an all-male, all-white student population for its first 60 years, change has been swift relative to its founding years.

“I think our university has done a great job over the course of history of being remarkably progressive around gender equity,” says Schwab. “I believe in the earliest days after Title IX, NC State embraced these probably more than many would realize for the kind of institution we had historically been.

“As we do with many things at NC State, we have done it quietly, not for the opportunity to move up in rankings or some sort of glory, but to create a more diverse population of students, faculty and staff on our campus.”

Schwab points to the administrative infrastructure put in place during the 1970s and ‘80s to face the changing demographics of a school that was founded on the 20th century principles of agriculture and technology research.

“In that time, we have created some amazing scientists, brilliant female researchers and accomplished alumna,” she says. “And we are now a predominantly female undergraduate institution.”

- Categories: