Better Care for Aging Dogs and Their Aging People

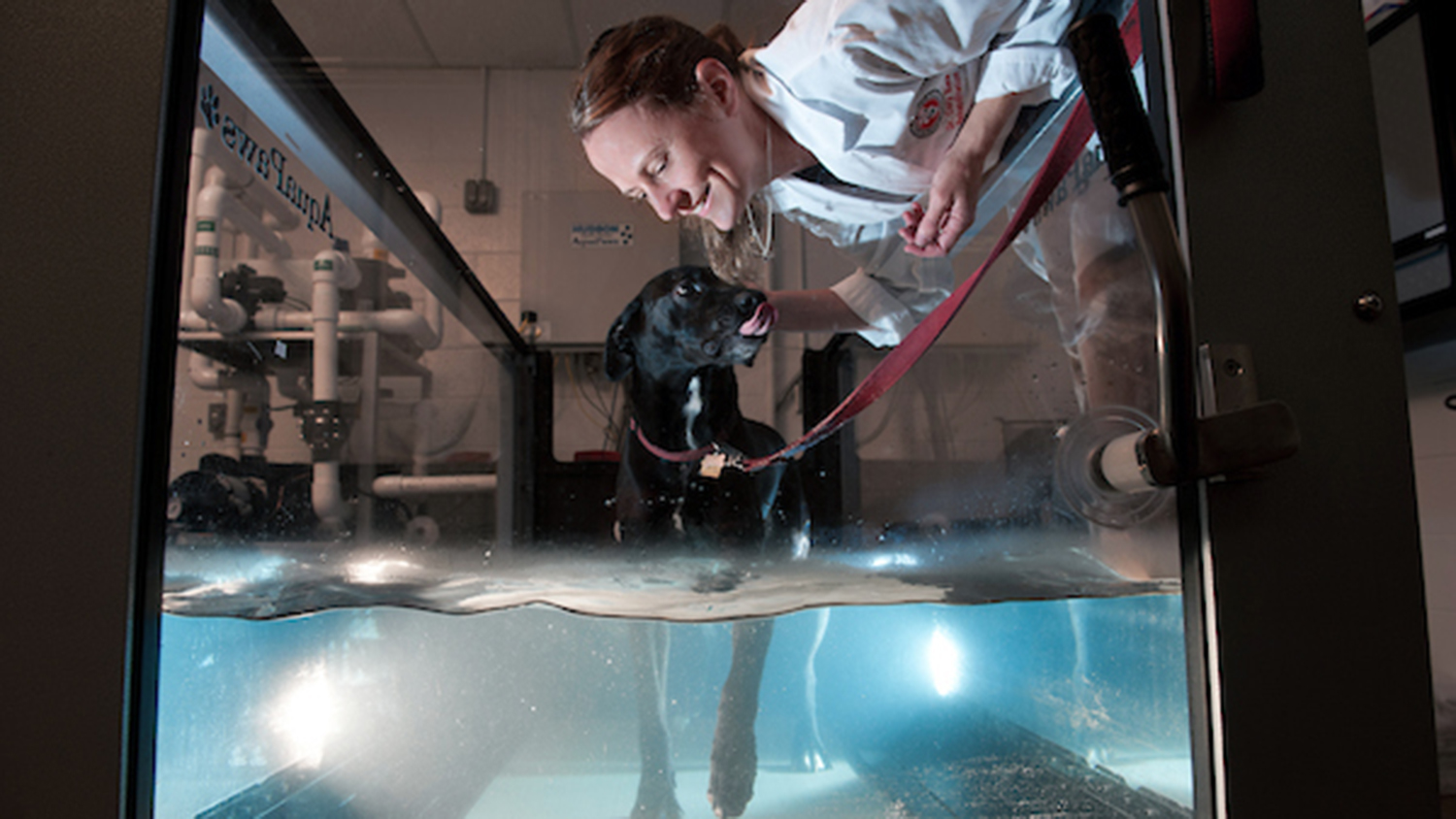

Natasha Olby’s lab in the College of Veterinary Medicine is generating data and insights into the aging process in dogs, and how to improve their health span — not just their life span. Her research also has implications for human geriatric medicine.

Dogs have a lot to teach us. In addition to the important life lessons we learn from our pets about friendship, joy and caring for others, dogs also provide veterinary researchers with a good model for understanding the effects of aging in people.

“Dogs allow you to look at the chronic influence of environmental factors and social factors in a really unique way,” said Natasha Olby, professor of neurology and the Dr. Kady M. Gjessing and Rahna M. Davidson Distinguished Chair of Gerontology in the College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM). “All of the research we’re doing on aging, we think, is potentially extremely relevant for people.”

This study of aging, or gerontology, is one facet of Olby’s canine research in the CVM. Her endowed chair in gerontology — currently the only position of its kind at a vet school with an associated research program — provides resources for her research into neuroaging and neurodegenerative diseases in dogs.

Olby has also introduced geriatric medicine into the curriculum of the CVM, helping to distinguish it from other vet schools by the degree of emphasis placed on this important and growing field. As dogs’ lifespans are increasing alongside human lifespans, there’s a growing need to study the impacts of aging on both dogs and humans.

“One of the big challenges to modern society is to maintain health span as well as lifespan,” said Olby. “Now, with improved health care for pets, dogs are surviving for longer and we come across the exact same challenge [as we do with people]. I think it’s critically important that we don’t say, ‘They’re just getting old,’ but we pay due attention to the process, understand which things we can alter within the process and advance our understanding of aging, in general.”

Treating Patients Is Research

The unifying theme of all of Olby’s research — which also includes spinal cord injury, the mapping of genetic diseases, and a neurodevelopmental disorder called chiari-like malformations — is that she works exclusively with hospital patients.

Unlike a traditional rodent model of studying disease, in which a disease is introduced to mice or rats in a tightly controlled lab setting, Olby’s research is conducted on aging dogs that are living with people in their homes. Her subjects are impacted by the same social and environmental factors that impact people as they age, because they live with people. They’re exposed to the same air that we breathe, often the same food we eat, the volume of exercise we engage in, the chemicals in our environments and the social structures of our families.

“There is so much opportunity there because the dogs are such a great model for humans,” said Kate Simon, a combined DVM/Ph.D. student who works in Olby’s lab. “There’s so much work in cognition, dementia and even just aging, in the field of human medicine. We see all the same things happening in dogs. We might perceive it or measure it a little differently, or call it slightly different things, but it’s all still happening.”

Olby started her program on neuroaging in dogs in 2018 with an initial goal of developing protocols that were safe and would not harm the dogs in any way. She wanted to find ways to quantify changes that can be observed in dogs as they age, such as mobility, postural stability, cognitive performance, vision, hearing and sense of smell. Through that study, Olby and her team were able to publish numerous papers on what happens to dogs as they age, and they now have enough baseline data to conduct clinical trials.

One clinical trial, run by Olby and Associate Professor of Behavioral Medicine Margaret Gruen, is currently underway, testing the impacts of two supplements on aging dogs. One boosts cellular levels of an enzyme that aids in metabolism, which decreases naturally as dogs age. The other supplement kills off senescent cells, or “zombie cells” that should have died but haven’t, which are consuming the enzyme and causing inflammation.

“It’s been a very exciting trial to run,” said Olby. “We’re learning a lot about doing trials in this population of very elderly dogs, with all the focus on developing new therapies safely.”

Simon is helping to run this clinical trial, which relies heavily on the dogs’ owners to complete regular questionnaires about their perception of their dogs’ quality of life, cognition and mobility at home. Working on this trial has increased her appreciation and affinity for working with pet owners, as she’s seen firsthand the bonds between them and their pets.

“You see such a great amount of care and the owners are really wanting them to have the best medicine, the best health and the best care in, potentially, the last leg of their life,” Simon said. “I just love seeing that.

“Because that is something that is quite different from human and veterinary medicine, is end of life and quality of care, and our understanding of geriatric medicine,” she added. “Dogs have someone who is their proxy, and it’s so much of what the owner is thinking and what the owner is perceiving their quality of life to be. So we’re trying to match that to what we notice objectively in the clinic, through our exams and through our gait analysis, and how that aligns with what the owners are seeing more subjectively.”

Results and Skills That Translate

Much of Olby’s research on aging in dogs is also increasing our understanding of the aging process in humans. For example, one disease that Olby’s lab has studied in dogs is degenerative myelopathy, which is caused by a genetic mutation that expresses itself with age and is comparable to an inherited form of Lou Gehrig’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), in people. The gene therapy trial they conducted for degenerative myelopathy provided a chance to study a naturally occurring dog model of ALS in people while developing new treatments for dogs.

This comparative or translational nature of Olby’s research, and the wealth of research being done at NC State, was part of what motivated Simon to attend vet school here. As a combined DVM/Ph.D. student, she is studying to become a veterinarian while also completing her doctorate in comparative biomedical sciences.

“I think NC State really exemplifies One Health and comparative medicine,” said Simon. “It seemed like the perfect fit and everything that I could ask for.

“It’s really cool to be at an institution that cares so much about research and really supports students who do come in with that background and want to pursue that, or haven’t been able to find the opportunity yet.”

There are opportunities for students at all stages of their higher education journey to get involved in research in the CVM. Olby has had students outside of the college join her lab, too, who are interested in science but want to do work with naturally occurring disease rather than induced disease. For students interested in veterinary medicine, she stressed that there are many possible careers beyond just the small animal veterinarian path that they might immediately picture — although working with humanity’s furry best friends is always an in-demand option.

“Veterinary medicine is a degree that will allow you to have a career that could take almost innumerable different directions,” said Olby. “You could go into public health. You could be an epidemiologist. You could be a pathologist. You could work in the community, in shelters. You can go and inform the DOD on biological warfare. A veterinary degree will give you such good training in so many different fields that you might find all kinds of different career options suddenly become very interesting to you.”

- Categories: