What Comes First: The Chicken or the Housing for a Cage-Free Egg?

NC State researchers found that hen breeds vary in their ability to adapt to cage-free environments. This can influence how farmers meet market demand for cage-free eggs and animal welfare goals.

Cage-free eggs have become a popular grocery purchase due to growing concerns about animal welfare. In early 2024, they accounted for roughly 40% of eggs sold.

For suppliers looking to help meet the rising demand for cage-free eggs, the solution may not be simply to do away with conventional hen houses. New research from NC State University suggests that not all hen breeds thrive in cage-free environments.

So maybe it does boil down to something like an age-old question. For egg producers, what comes first: The chicken or the housing for the cage-free egg? That is, should poultry farmers start by considering which breed thrives best in a cage-free environment? Or should their facilities inform which breeds they choose?

Genetic Variables

In a typical cage-free environment, thousands of hens are free to roam inside a poultry barn. Problems appear, however, when skittish hens injure themselves by crashing into walls or workers.

NC State researchers examined which genetic strains of egg-laying hens exhibit less stress responses and adapt best to cage-free housing. The implications could provide guidance for commercial egg producers, helping them balance market demands with the welfare of their hens.

In a 72-week study, researchers evaluated behavioral responses and egg production for four strains of hens in cage-free environments. The research included white leghorn hens, genetic strains H&N White and Hy-Line W-36 — breeds typically raised in cages in conventional poultry houses — and Hy-Line Brown and Bovan Brown hens. The brown breeds are most often raised in cage-free, pasture-raised or free-range systems.

Each strain was housed in a separate 10×4-foot pen, equipped with a roost, a three-rung ladder perch and four nesting boxes.

“It’s an environment that would be equivalent to a single-level, cage-free system on a commercial scale,” explained Bhavisha Gulabrai, a doctoral student at NC State who conducted the research while studying for her master’s degree in poultry science.

Testing Adaptation Responses

To measure stress in the birds, Gulabrai worked with Allison Pullin, an assistant professor of animal welfare in NC State’s Prestage Department of Poultry Science. Pullin utilized two testing methods to measure behavioral reactivity in the hens.

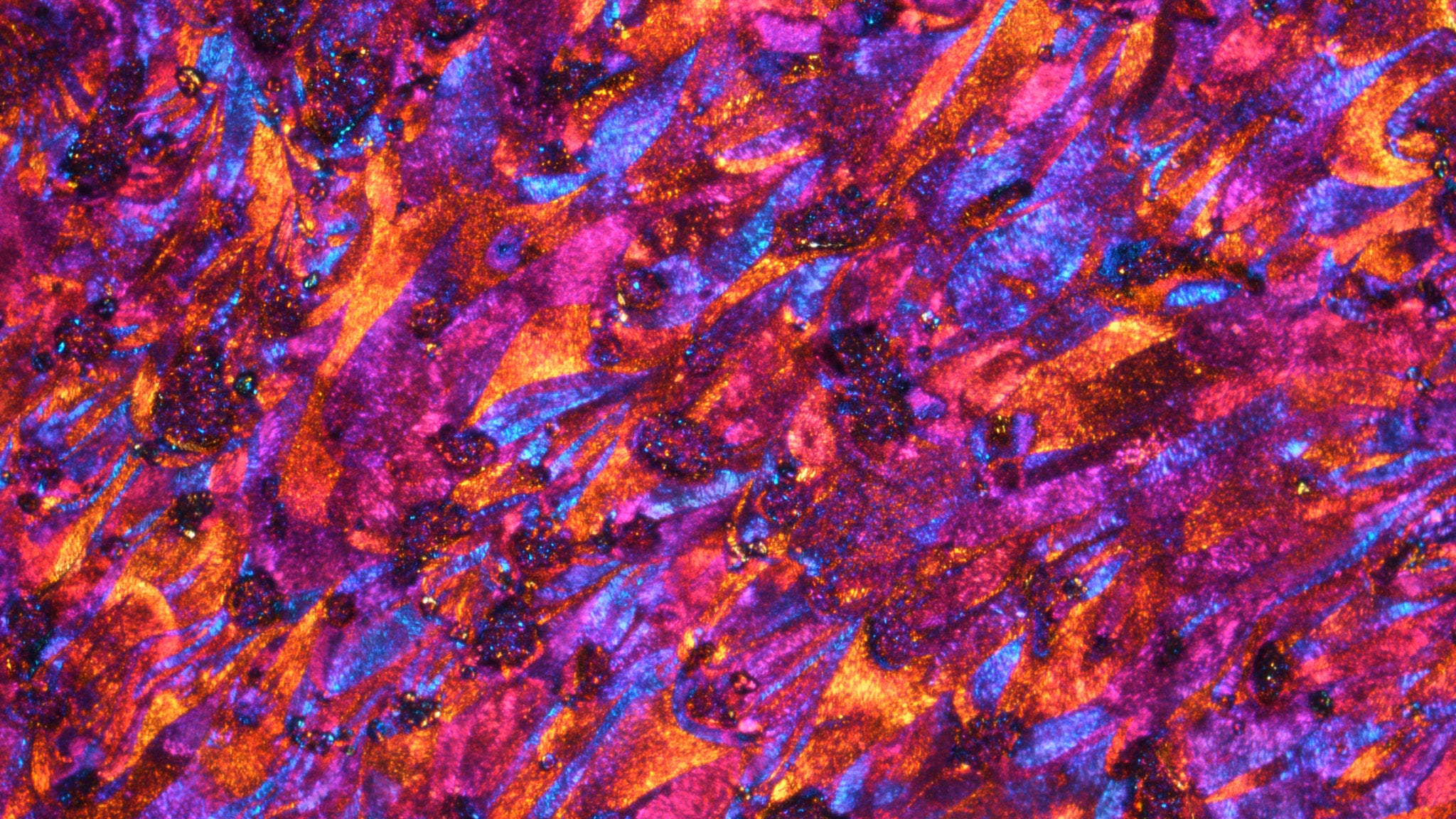

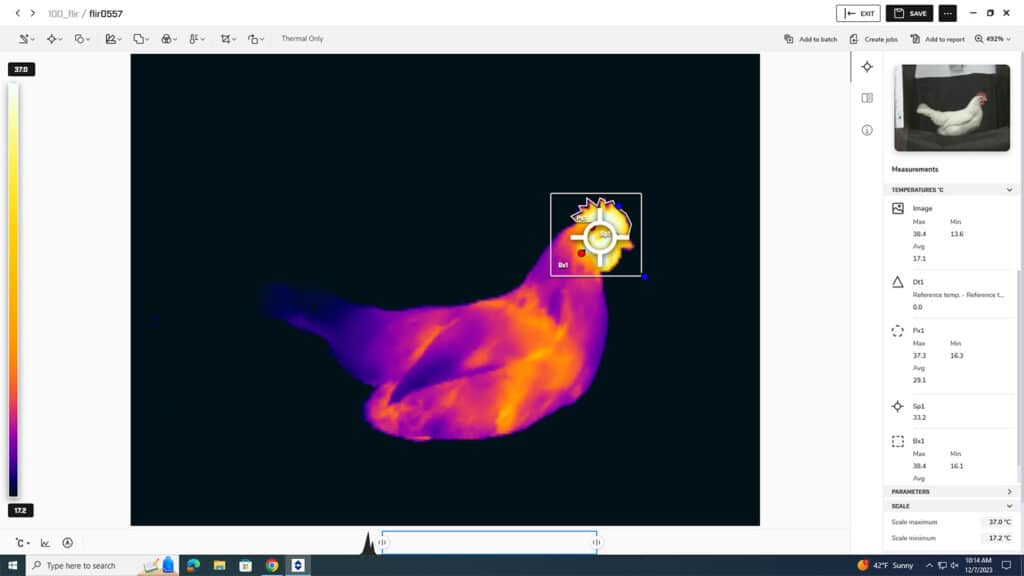

In one test, the hens were given a few days to acclimate to their new cage-free housing before a loud sound was played to startle them. Another test involved handlers turning the birds upside down to observe how intensely they flapped their wings, and then measuring changes in their blood flow using thermal imaging.

“When you think about a fight or flight response, an animal undergoes these almost immediate vascular changes to try to direct blood flow to the most crucial arteries,” Pullin said. “Looking at the degree of temperature change, as well as how rapidly it changes, can give us an interesting physiological measurement about how that animal is really coping with stress.”

After both tests, the researchers observed how long it took for the hens to resume their normal, more relaxed behavior.

The white strains of hens, the Hy-Line W-36, did not undergo the behavior tests. They had been reared in cages prior to the start of the study, a factor that made them least likely to acclimate to the cage-free housing and would mislead the test results.

Egg Production in Cage-Free Housing

To measure production, 18 eggs were randomly collected from each strain, then sorted and separated into three groups to undergo analysis. The research examined characteristics such as shell strength, yolk color and grades by USDA standard.

The test results showed that the brown strains performed best overall.

“When we looked at production and egg quality, the Hy-Line Brown strain did better than the three other strains used in the study. They just had better egg production and better egg quality metrics compared to the three other strains,” said Bhavisha Gulabrai, who is pursuing a Ph.D. in agricultural and human sciences at NC State with a concentration in agricultural communication.

The H&N White hens ranked lowest.

“We think that they probably had a more difficult time adjusting to the cage-free system,” Gulabrai said. “Visually and anecdotally, white strains are more flighty, and our H&N White strain remained pretty flighty throughout the entire 72 weeks.”

Still, the results were not so clear-cut. Bovan Browns were the least efficient, consuming the most feed while laying smaller eggs.

The researchers recommend that egg producers review the research findings with their own facilities in mind, as cage-free poultry housing can vary.

“The farmer knows what kind of housing they have, so they would have to consider these results and make decisions based on what they think the best strain would be for their particular housing environment,” said Gulabrai.

For now, the current research appears to put the question to rest: the housing suppliers already own should be the first thing to consider, helping them determine which hens are likely to adapt best.

The research was published in two papers examining a distinct aspect of the findings. Exploring the implications on egg production, the authors published the paper, “The Influence of Genetic Strain on Production and Egg Quality Amongst Four Strains of Laying Hens Housed in a Cage-Free Environment.” Focusing on animal behavior, the researchers published “The Influence of Genetic Strain on Fear and Anxiety Responses of Laying Hens Housed in a Cage-Free Environment.”

Both papers were also co-authored by Ken Anderson, a professor and director of the North Carolina Layer Performance and Management Program, and Aaron Kiess, Braswell Distinguished Professor in the Prestage Department of Poultry Science.

This article is based on a news release from NC State University.