Leading the Pack Out of the Pandemic

College of Veterinary Medicine microbiologist Megan Jacob’s new in-house lab is surveilling COVID-19 on the NC State campus.

Editor’s Note: This is a guest post by Jordan Bartel, communications strategist in the College of Veterinary Medicine at NC State.

Megan Jacob is a mother of three who just got her second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.

She’s also an associate professor in clinical microbiology and director of Diagnostic Laboratories at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM). Now, under her leadership, the college is home to COVID-19 testing labs for the NC State community.

With the laboratories capable of completing 8,000 tests per day — and current expectations for campus demand at about 11,000 tests per week — much of the university community’s health is in the hands of her and her lab team.

It has truly brought out some of the best in people.

“I’ve hired some really great people in our lab who, in their cover letters, say, ‘I just want to contribute to fighting the pandemic,’” says Jacob. “It has truly brought out some of the best in people.”

The labs are part of NC State’s wider COVID-19 testing program WolfTRACS, short for “testing, reporting and COVID surveillance.” The campus is working closely together through WolfTRACS, from test collection by Student Health Services, the campus surveillance program and now fast testing of samples at the CVM.

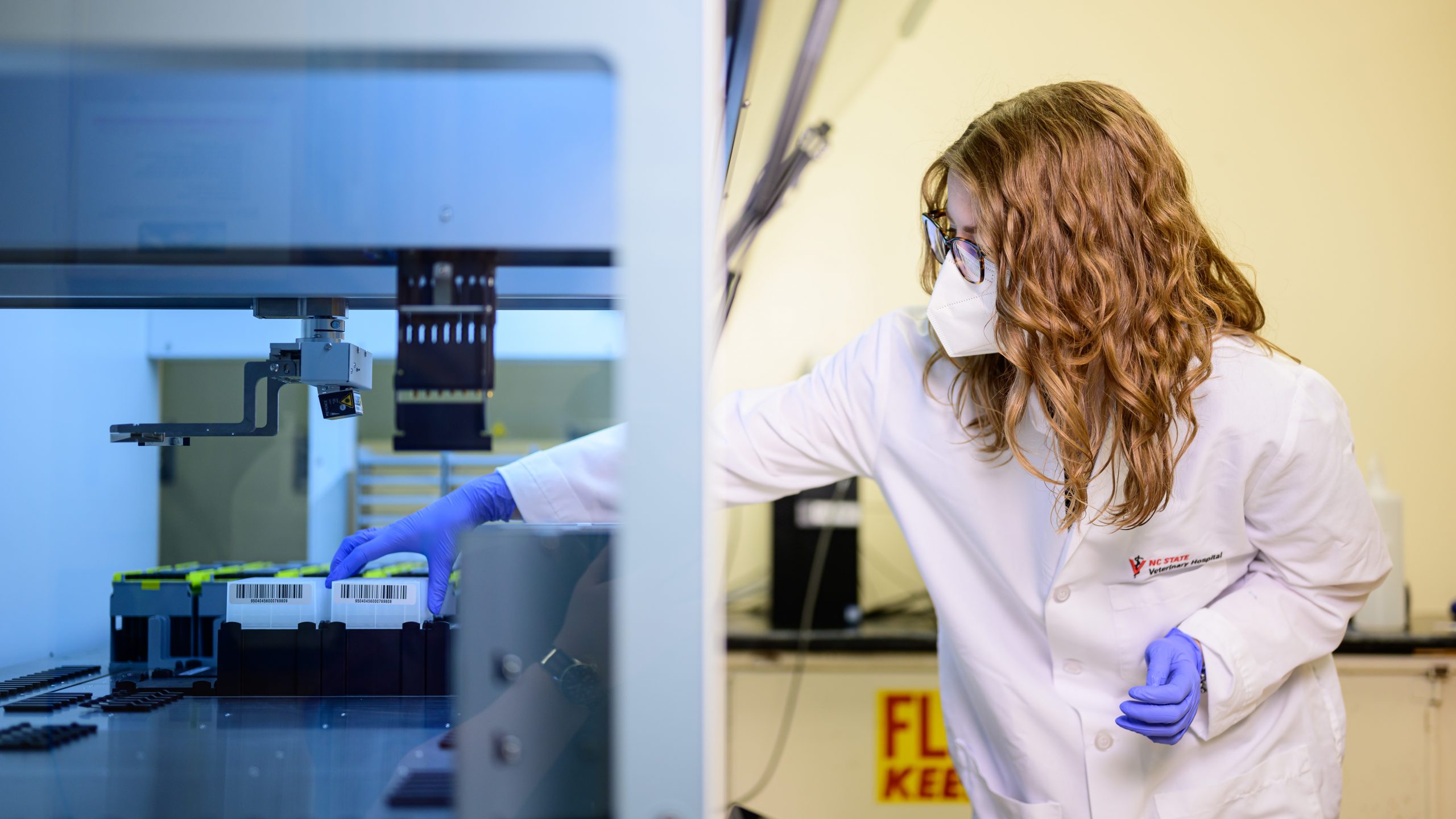

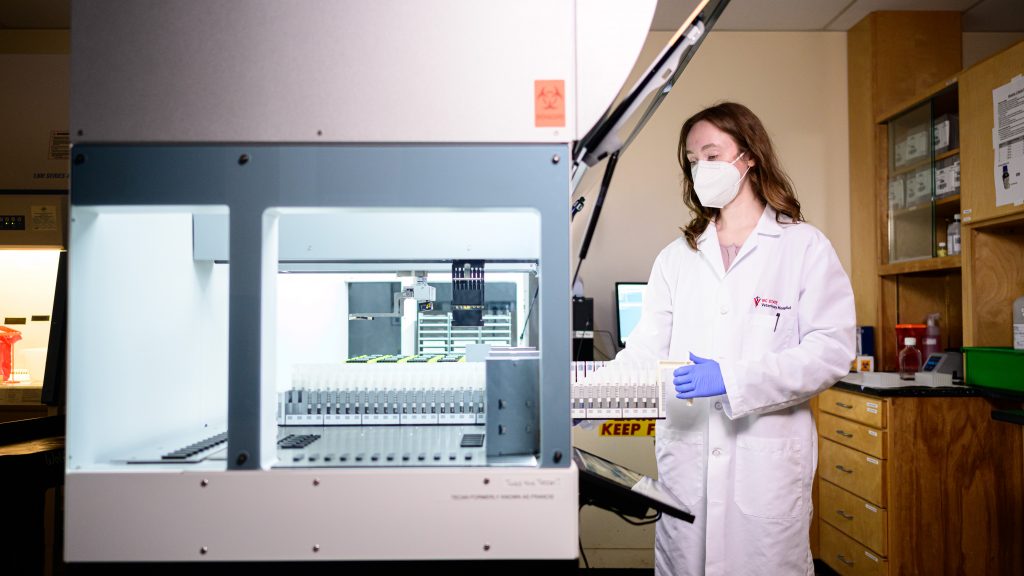

The automatic real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) robotic testing machine in one of the labs is working hour upon hour, day after day, testing nearly 400 samples at a time. NC State required all students, faculty and staff returning at the start of the spring semester to show a negative COVID-19 test before returning to campus. The testing is free. Face coverings continue to be required everywhere on campus, inside and outside, with few exceptions. Ongoing weekly surveillance testing is required for certain populations throughout the spring semester. (For more on surveillance efforts, visit Protect the Pack.)

Jacob talked to us about the efforts to make the COVID-19 labs a reality, how she has been affected by the pandemic and why she feels optimistic about turning the COVID-19 tide.

What impact will these in-house testing labs have on the health and safety of the NC State community?

We would like to have a very low presence or prevalence of the virus on campus for a lot of different reasons. It allows us to feel more comfortable in doing some of the more routine experiences and tasks, and it keeps people safe who are at risk for developing severe COVID.

The more people we test and the better our idea of what our true prevalence is, the better we can make decisions. Most of the time when people are sick, they seek out testing or self-quarantine. That’s not really the idea behind the surveillance lab. We want to find those people who are asymptomatic or presymptomatic, who may not know they’re shedding it on our campus, and getting those folks isolated as fast as possible.

How does this work help the larger community off campus, including the Raleigh metro or even the state as a whole?

When we’re testing people here on campus, we are keeping those tests from going elsewhere and taking up valuable resources from other commercial testers. I think that it also includes people that may not otherwise have been tested. It’s definitely providing data that we can use locally at NC State, but also within the region to understand what the virus is and how it’s spreading and what the prevalence is.

What is a typical day like in your lab?

It starts with the sample collection. We receive shipments from various collection sites across campus. Our testing machine operates most efficiently if we’re looking at 376 individuals at a time. So if we can evaluate 376 samples, it’s efficient and cost-effective.

People may start collecting at 6 or 7 or 8 a.m., and it’s probably about 10 a.m. when we start processing in the laboratory. We make sure that the samples are in good condition and then we put them in an incubator at high temperature for a period of time to make sure that the virus is no longer infectious if it’s present. After we heat-inactivate it, then we put it onto what’s called module one, the first machine.

The machine reads the barcode, takes a sample out of the test tube and puts it into a 96-well dish. Then we transfer them safely and securely to the other lab where they go on to a really large robot that does the viral RNA extraction, sets up the PCR and then ultimately runs the assay.

That whole process takes three-and-a-half to four hours from start to finish. Then we look at results and our results automatically populate student health records. We go through that process somewhere between three and four times a day.

As a microbiologist, what has it been like for you to watch the pandemic unfold?

When you do infectious disease and microbiology work, there is this natural curiosity, interest and professional responsibility to want the help and contribute in some way. Early on, I started serving on the CVM COVID response advisory group. We also got prepared to test through our veterinary diagnostic labs. Part of the reason why we were well-positioned to take on the labs was that we’d already done COVID detection on animals. We had the safety plans in place to do that.

I think that it was kind of energizing and exciting because of the type of work that microbiologists do anyway, and it just felt like it was a way to contribute and give back.

Even with your background, have you ever been a part of something similar to this?

Most people in my line of work have gone through courses where we talk about great pandemic responses and have done analyses of similar types of events. Although we probably were better prepared than most to know that something like this was coming, it’s not as surprising or shocking to us. But I really don’t think that there’s been an experience that’s been similar even in the animal populations I’m used to working with.

In the beginning, the focus was on answering questions, trying to figure out what this was and developing different approaches to testing. Now that you actually have this procedure in place, what does that feel like?

I think it’s amazing to see how science has evolved to respond to things so rapidly. That piece of it is so exciting. We understood the virus very quickly. We could do analysis very quickly. There was published literature and recommendations faster than there’s ever been. There’s the vaccine development. There are these robots like what is in our lab that can now detect this in six hours.

When we first started the work during the pandemic, we were at 72 hours being a really good turnaround time. So that piece of it has been quite incredible to see, just how efficient we can make the response.

It has been quite incredible to see, just how efficient we can make the response.

Has there been a moment recently that has been particularly encouraging to you, that indicates that we’re on the right track?

I think just anecdotally watching people’s compliance for masks and their push for other people to adhere to good practices has been really encouraging. I know that was really controversial at the beginning, but we’ve moved up as far as public health understanding of that importance. I think people are really quite receptive to testing and contributing to our campus and our region’s data to understand what is going on.

Creating the labs was a large collaborative effort. How did it all come together?

To do surveillance of 11,000 people per week required a different technology than we had on campus. So we started partnering with commercial vendors that could offer that, and it’s extremely expensive to do that. The administration saw value in needing to know what our risks here on campus were in order to get back to any sort of normalcy. We put together a document that said, ‘OK, if we want to do this ourselves, here’s what that would look like.’ Julie Swann, head of the Fitts Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering; Angela Harris, assistant professor in the Department of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering; Matt Koci, NC State professor of immunology, virology and host-pathogens interactions; and others contributed to that initial push to look at what it would take to do it internally.

Where did you go from there?

We created a spreadsheet that broke down elements like cost per test and the technology we needed. CVM Dean Paul Lunn sent it to the administration on Main Campus, and it was about a third of the cost that they were paying to do testing currently. Then we made it happen. We chose the complete robotic automated system. We worked with faculty on campus to find spaces that may be available. The facilities crew worked really hard over the holidays to get them organized for the machines.

NC State Student Health Services and Emergency Management and Mission Continuity were two other big partners in this. We started receiving 40,000 test kits every three weeks on six pallets. And the production recycling crew came in.

When we started to go with this plan at the end of last semester, we didn’t have any technicians for these positions. CVM and university human resources worked to speed that up and find the best candidates. By January 19, I had four people who were prepared to start in our lab.

I don’t know how that all happened, but everybody truly, collectively came together. They said, ‘This is coming. We need to be ready.’ And we are.

Everybody truly, collectively came together. They said, ‘This is coming. We need to be ready.’ And we are.

How has the pandemic affected you personally?

I think that it’s probably similar to most people. It’s very heavy at times because we’ve had to cancel trips or we’ve had to ask family not to visit when we would really like them to be there. We know people who have been sick with COVID.

I think for me, there’s also this added piece of responsibility to set an example and try to do the right thing and live in the right way, because I feel like I have the advantage of knowing more about how the virus works.

People have made personal decisions for themselves and we’re no different. I think one of the advantages to knowing more about the virus and more about the epidemiology is that I feel like I’m pretty well-informed to assess risk. I feel very comfortable when we make a decision.

Looking forward, what keeps you optimistic about efforts to curtail infection rates within the campus community and the state?

We went through a really rough period in December and January, and I think we’re all really encouraged by watching those infection numbers drop as steadily as they have. That’s been reflected on our campus; right now we have a very low positivity percentage.

When I was getting a second dose of the vaccine, there was a lot of excitement at the hospital. It wasn’t a sense of dread. People were volunteering and really excited to be getting other people vaccinated.

If we get down to such a low prevalence that my lab isn’t needed, that’s actually a good thing. If what we’re told in June is that we’re good, that we’re no longer needed, that’s what we want to hear.