Museum Specimens, Modern Cities Show How an Insect Pest Will Respond to Climate Change

For Immediate Release

Researchers from North Carolina State University have found that century-old museum specimens hold clues to how global climate change will affect a common insect pest that can weaken and kill trees – and the news is not good.

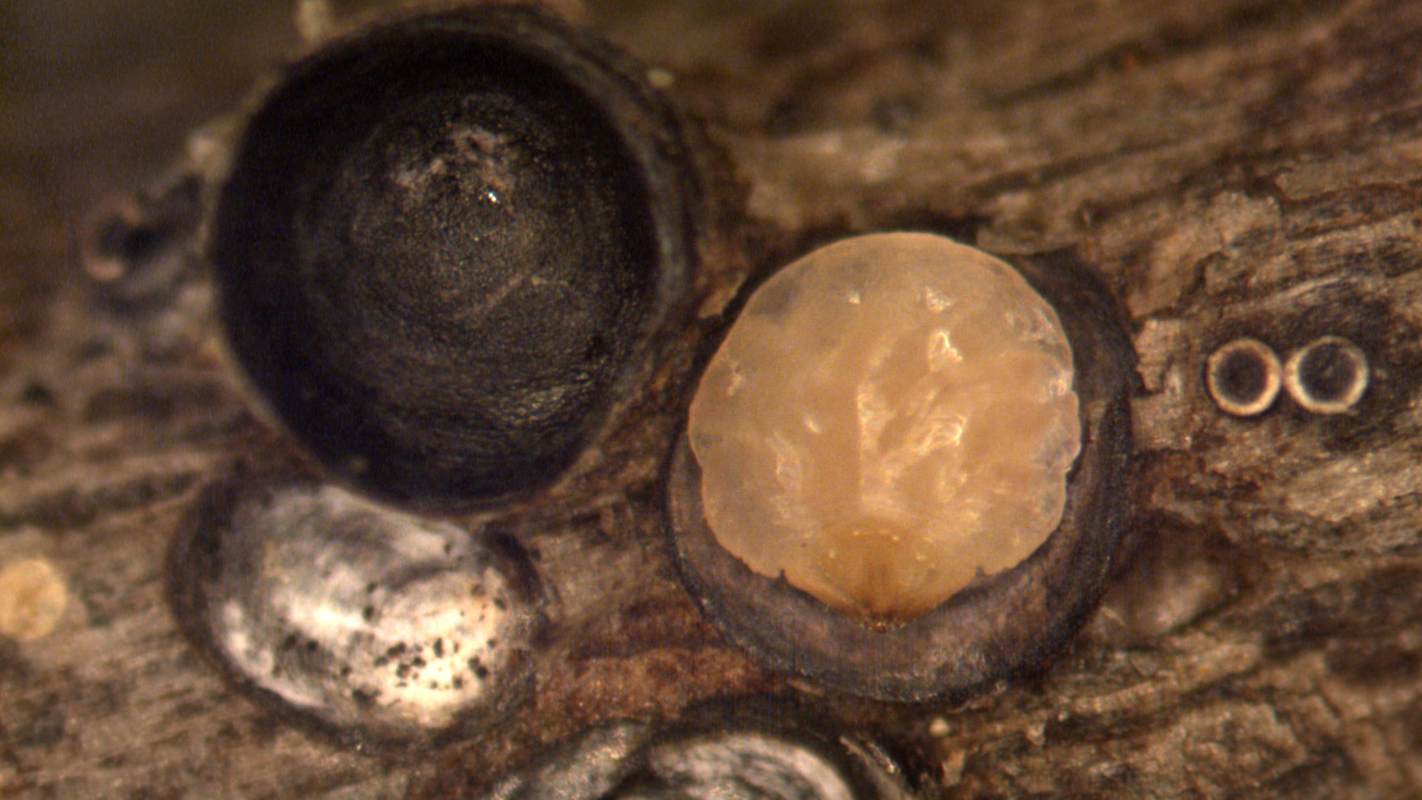

“Recent studies found that scale insect populations increase on oak and maple trees in warmer urban areas, which raises the possibility that these pests may also increase with global warming,” says Dr. Elsa Youngsteadt, a research associate at NC State and lead author of a paper on the work.

“More scale insects would be a problem, since scales can weaken or kill the trees they live on,” Youngsteadt says. “But cities are unique, so we wanted to know whether warming causes scale insect population explosions in rural forests, the way it does in cities.”

To address that question, Youngsteadt examined more than 300 museum specimens of red maple branches collected between 1895 and 2011 in rural areas of North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. By evaluating the scale insect remains attached to each specimen, Youngsteadt estimated scale population density and compared it to the average August temperature for the year and place where the specimen was collected. Youngsteadt then compared the findings from the historical specimens with more recent data from urban Raleigh, North Carolina.

“Scale insect density in rural areas was not as high as it was in the city, but there was a common pattern,” Youngsteadt says. “Scale insects were most likely to be present on specimens collected during warm historical time periods, and scales were most abundant when temperatures were similar to modern, urban Raleigh.”

Given the shared urban and historical pattern, the researchers also predicted that scale insects would be more abundant in rural forests today than in the past, as a result of recent climate warming. To test this prediction, Youngsteadt went to 20 sites where historical specimens were collected from 1970 to 1997 and sampled their modern scale insect populations.

“Sure enough, scale abundance had increased at 16 of the 20 sites,” Youngsteadt says. “Overall, we found a total of about five times more scale insects in 2013 than on the historical specimens from the same locations.

“The urban and historical data are so well-aligned that we can view scale insect populations in cities as a preview of what to expect elsewhere,” Youngsteadt adds. “It also suggests that we should begin looking at cities for clues to how other insect species will respond to higher global temperatures.”

The paper, “Do cities simulate climate change? A comparison of herbivore response to urban and global warming,” is published in the journal Global Change Biology. Co-authors include Adam Dale, Dr. Rob Dunn and Dr. Steve Frank of NC State, and Dr. Adam Terando of the U.S. Geological Survey and NC State.

The results are consistent with other recent studies from Frank’s lab, which showed that two species of scale insects infesting maple and oak benefit from urban warming. The new study suggests that these urban studies have broader relevance not just to cities but also to global warming in rural areas.

The work was supported by USGS via the Department of Interior’s Southeast Climate Science Center, which is based at NC State and provides scientific information to help natural resource managers respond effectively to climate change. The research was also supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture under grant 2013-02476, and by the National Science Foundation under grants 0953390 and 1318655.

-shipman-

Note to Editors: The study abstract follows.

“Do cities simulate climate change? A comparison of herbivore response to urban and global warming”

Authors: Elsa Youngsteadt, Adam G. Dale, Robert R. Dunn, and Steven D. Frank, North Carolina State University; Adam J. Terando, U.S. Geological Survey and North Carolina State University

Published: Aug. 27 in Global Change Biology

DOI: 10.1111/gcb.12692

Abstract: Cities experience elevated temperature, CO2, and nitrogen deposition decades ahead of the global average, such that biological response to urbanization may predict response to future climate change. This hypothesis remains untested due to a lack of complementary urban and long-term observations. Here, we examine the response of an herbivore, the scale insect Melanaspis tenebricosa, to temperature in the context of an urban heat island, a series of historical temperature fluctuations, and recent climate warming. We survey M. tenebricosa on 55 urban street trees in Raleigh, NC, 342 herbarium specimens collected in the rural southeastern United States from 1895 to 2011, and at 20 rural forest sites represented by both modern (2013) and historical samples. We relate scale insect abundance to August temperatures and find that M. tenebricosa is most common in the hottest parts of the city, on historical specimens collected during warm time periods, and in present-day rural forests compared to the same sites when they were cooler. Scale insects reached their highest densities in the city, but abundance peaked at similar temperatures in urban and historical datasets and tracked temperature on a decadal scale. Although urban habitats are highly modified, species response to a key abiotic factor, temperature, was consistent across urban and rural-forest ecosystems. Cities may be an appropriate but underused system for developing and testing hypotheses about biological effects of climate change. Future work should test the applicability of this model to other groups of organisms.

- Categories: