Above the Battlefields of World War I

The Memorial Tower | World War I Transformed NC State | The Names in the Belltower

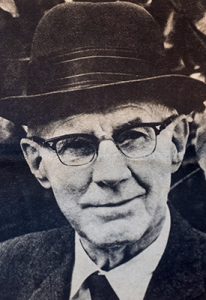

No one had a better view of the battlefields of France during the First World War than NC State civil engineering alum Jimmy Higgs.

And few people survived the danger he faced, as the leader of one of 17 U.S. balloon observation companies that served on the Western front.

James Allen Higgs Jr., a native of Raleigh and a two-time graduate of the North Carolina College for Agriculture and Mechanic Arts (1906, ’10), signed up for duty at the mature age of 29, intent on going to war, just like his slightly younger classmate Frank Martin Thompson (1910).

Higgs was a slight fellow of 5 feet, 5 1/2 inches, weighing 120 pounds in a cold sweat. His greatest ambition, he said just before his graduation, was “to grow.” He knew that if he signed up as an infantryman, he likely would not survive more than a few days in the trenches that bisected the open fields of France, Belgium and Germany.

“I was a little guy, and I couldn’t fancy myself swapping bayonet thrusts with those big Germans,” Higgs told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 1968 in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the end of the First World War. “When the call went out to be balloon observers, I volunteered.

“They took us to Washington and put us in a machine and spun us around until we were thoroughly dizzy, then measured the time it took to regain our equilibrium. I was one of the winners.”

Being a “balloon spy,” as he was often called, was a position unique to the Civil War and World War I. Every day, from sunrise to sunset, it was Higgs’ assignment to crawl into a two-man basket tethered by cable to the front of a truck. Armed with binoculars, topographical maps and a telephone, he would fly high (up to 5,000 feet) over the battlefield and report troop activity to his commanders on the ground. Usually, he was with a French observer who was relaying similar information to his superiors.

As if flying unprotected over the battlefield wasn’t dangerous enough, the sausage-shaped gasbags were filled with highly flammable hydrogen, making them susceptible to fires started by the hot rounds coming from guns below. They were also sitting-duck targets for the biplanes that attacked from behind the clouds overhead.

Four times over the course of four months, Higgs was shot down, jumping out of the basket and praying that the parachute stuffed on the outside of the balloon basket and harnessed to his back automatically deployed after he cleared 300 feet.

Each time, he went right back up.

Once, he was trying to coerce his partner to escape for his life and was met only with a blank stare from a non-English speaking partner. He quickly ran through his memory banks to find the French word for “jump.”

“We were supposed to stay in the balloon until our telephone man on the ground told us to jump,” Higgs told the AJC. “Noise carries upward much louder than along the surface. The guns were making such a racket I couldn’t hear over the phone.

“Finally, I made out the words ‘Jump! Jump!’”

When he relayed the order to the French sergeant, he got no response.

“I realized he didn’t understand English, and hollered, ‘Sautez! Sautez!’ and pointed the way he was to go. He went over the side and I followed him.”

It was anything but a peaceful trip to the ground.

“We were each wearing parachute harnesses with a rope attached to the ‘chute that was stuffed into a bag hanging outside the basket. Our weight would pull the ‘chutes out of the bags. They were supposed to open when we dropped 300 feet. It takes nearly five seconds to fall 300 feet from a standing start, and that is a long time to wonder whether you are going to live or die.

“The parachute opened with a considerable jolt, but it was a very pleasant feeling. I closed my eyes until the parachute popped, but I kept them open on subsequent jumps.”

Higgs’ only compensation for jumping out of a falling balloon on four occasions? Each time, he was awarded 48 hours of leave in Paris to “settle his nerves and get ready to go back up again.”

Which he did until Nov. 11, 1918, when the bells of Paris signaled the pre-arranged armistice between the warring forces. Weather did not allow Higgs to go up at the time of the ceasefire, but the following day he did up to 5,000 feet — the limit of his balloon’s steel cable — to make sure German forces were pulling out as promised.

“The end was an amazing thing,” he said. “I had been hearing guns roaring around and under me, and sometimes, enemy shells and bombs bursting in our camp, for almost a year,” Higgs said. “Sharp at the stroke of 11, they all stopped. There were no birds or animals in the war zones to make the usual noises, and no machines moved.

“I found myself listening for just any sound, but there was none.”

Higgs chronicled his balloon exploits in detailed letters to his mother, Mattie A. Higgs, who lived on Raleigh’s North Blount Street from 1889 to 1964. They were retold many times through the years to his NC State brethren during his visits from Atlanta, where Higgs settled after the war, to Raleigh, where his family remained.

Higgs was a loyal and devoted NC State alum and served as the president of the Alumni Association in 1938. A vice president and regional manager of the Massey Concrete Products Corp., Higgs never missed an Atlanta-area alumni meeting.

He was twice awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest honor given by the U.S. Army, for extreme gallantry and risk of life during his daily work as a balloon observer.

While Higgs survived his 18-month service, unlike so many who are celebrated annually on Memorial Day, he did know the tragedy of war. His father and three uncles were part of the 3rd North Carolina Cavalry in the Civil War.

And he and wife Mary Marbury — a descendant of North Carolina’s first governor, Richard Caswell — were the proud parents of two sons, James Allen Higgs III and Caswell Marbury Higgs. The younger son followed his father’s footsteps as a military hero, enlisting in the U.S. Army in 1942 as a second lieutenant, shortly after completely his sophomore year at the Citadel in Charleston.

A machine-gun platoon leader, Caswell Higgs was shipped overseas in 1944 and landed on Normandy’s Utah Beach two months after D-Day. Serving in the Army under Gen. George S. Patton, the younger Higgs was killed in action five months later, leading his men across the Rhine River. He was posthumously awarded the Silver Star for bravery on the battlefield, making him a second generation war hero.

Higgs’ grandson, James Allen Higgs IV, was an Army Ranger in Vietnam.

Higgs died June 30, 1971, at the age of 83 and was buried in a private cemetery in Atlanta. But he never forgot his Raleigh roots, his NC State education or his fallen comrades.

In March 1919, just weeks after returning from France, Higgs was among the first alumni to donate to the proposed Memorial Tower to honor the NC State soldiers who perished in Europe’s Great War, by sending a check for $5 to director E.B. Owen in the Alumni Office.

- Categories: