Event Highlights Legacy, Work of African American Cultural Center

It takes some time to explore the African American Cultural Center. Colorful Afrocentric art adorns the gallery walls on the second floor. The library contains more than 7,000 titles by and about people of African descent. On the third floor, a large piece of art featuring historical icons — among them Booker T. Washington, Malcolm X and Sojourner Truth — greets visitors at the double doors. There are offices, meeting rooms, places to study and an open area with sofas and lounge chairs that invites visitors to hang out.

Everything speaks to the center’s purposes. It’s a place to learn about the history and experiences of the African diaspora. It’s a place where black students can be themselves. It’s a place to celebrate African-American culture and pride.

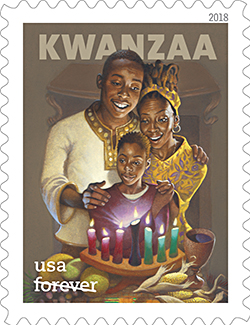

That celebration takes the national stage on Wednesday when the United States Postal Service dedicates its 2018 Kwanzaa stamp in the center’s Washington-Sankofa Room. Along with the official stamp dedication, the event will include music, dancing and remarks by notable figures, including the center’s first director, Iyailu Moses, and first program coordinator, Toni “Mama” Thorpe.

Director Moses T. Alexander Greene put together the pitch that persuaded USPS to choose NC State’s African American Cultural Center for the unveiling, describing the center’s commitment to educating people about the histories, cultures and experiences of African-American and pan-African people. But the real hard work, he says, happened decades before.

“Today’s honor belongs to the alum,” he says. “The honor reflects a legacy of intellectual brilliance and a determination of spirit that countless students of the African diaspora who matriculated here embodied. Their voices — as well as those of key faculty, staff and administrators — prepared the ground for this moment.”

The stamp dedication is a significant moment, but it doesn’t mean the center stops persevering. A new generation of staff is continuing the work of advocating for people of color and pushing for equality.

A Different Era a Short While Ago

It’s been just 60 years or so since NC State saw notable firsts. The first African-American undergrads enrolled in 1956: Walter Holmes, Manuel Crockett, Ed Carson and Irwin Holmes — a tennis player who also become the university’s first African-American athletics team captain. The first African-American faculty member joined in 1962. In 1969, the university offered its first black studies courses, including the Afro-American in America and Black American Literature.

The African American Cultural Center was another notable first. Students started out in the basement of the campus YMCA — now Kamphoefner Hall — in 1970. Five years later the center moved to the Print Shop — now the West Dunn Building — also known as “the hot box” for its lack of air conditioning. The center opened in its current home in 1991 in the Student Center Annex, now Witherspoon Student Center, named for Augustus Witherspoon, the first African-American teacher in university history to achieve the rank of professor.

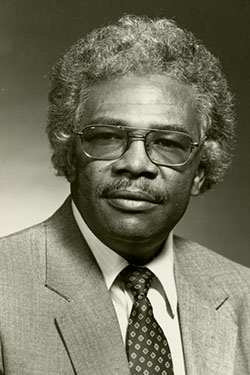

Witherspoon is credited as a founding father of the cultural center, along with Lawrence M. Clark, the university’s second African-American administrator. They wanted students to take what they learned and use it to improve their communities and cities. They also had one particular goal for the center that distinguishes it from others in North Carolina, Greene says.

“From our origins, it was important to Dr. Witherspoon and Dr. Clark that the center would be an academic unit,” he says. Greene’s Kwanzaa stamp pitch to the Postal Service emphasized the center’s dedication to scholarship and research.

The center is continuing its founders’ vision. Assistant Director Sachelle Ford joined the center in May and is in charge of faculty outreach, positioning the center as a partner in research and work related to Afrocentric topics. That takes many forms, including dissertation writing groups, mixers for black graduate students and faculty, and consultation with instructors. Last year, the center gallery featured a virtual-reality project by College of Design professor Derek Ham that let visitors experience the 1968 sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis, Tennessee, and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. In the spring the center joined with the Department of Biological Sciences and the NC

State Women’s Center for a screening of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, where students, faculty and members of the community discussed biomedical ethics, race and eugenics.

Greene invites colleges to use the center for programming that reflects African diasporic research, scholarship and issues. “We’d love for those discussions to happen here.”

Some organizations are already using the center’s space. Earlier this year the center hosted a Women’s Center photo gallery, “The Politics of Black Hair,” which delved into the symbolism of hair and the obstacles black people face in wearing it freely. Later this month the African American Cultural Center and the GLBT Center will present “Artivism: Advocacy and Activism through Art” with displays by local artists who showcase activism, justice, resistance and self-love.

“It’s very important to me that our exhibits are not just aesthetically pleasing but pedagogically intriguing,” Greene says.

Everyone Can Learn Something

The center engages in other types of outreach through programming. “What’s on the Table?” is a series of weekly sessions that encourages discussion on Afrocentric topics. The annual Harambee, Swahili for “let us come together,” invites students, faculty and staff to celebrate the beginning of the school year and its potential for individual growth and connection with the community.

Much of the programming is thanks to Thorpe, who served as the first program coordinator from 2001 until her retirement in 2017. She invited many notable speakers to campus, including King’s daughters; Joseph Holt, whose Raleigh family tried to enroll him in a white school after the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board ruling; and Pearl Cleage, writer of novels, plays and nonfiction works. Turnout was often standing-room only, and some speakers were taken aback by the audience, Thorpe remembers.

“When Joe Holt came, he said — and he was almost teary-eyed — he said, ‘I never dreamed when I was going through so much change as a child with my family that I would walk into a room at NC State and it would be filled with 50 percent white people.’”

The center welcomes everyone to its events, especially the curious. The USPS stamp dedication is not just for people who celebrate Kwanzaa; it’s for people who would like to know more about Kwanzaa, from what it is to why it’s on a stamp in the first place. The dedication dovetails with the center’s newly updated mission “to promote cultural intelligence, identity exploration and knowledge of the richness and diversity of diasporic communities for the campus and surrounding communities.”

Cultural intelligence means accepting that people of different demographics can live in the same country, state, even residence hall, and have completely different experiences. It means walking in someone else’s shoes — strange and uncomfortable at first. People have to be open to new ideas and viewpoints instead of dismissing them because they don’t align with their own personal experiences.

“I think we all have to learn together that just because my lived experience is not that, does that mean I can’t support that?” Greene says. “Does that mean I cannot be an ally?”

Overcoming prejudice requires honesty, Thorpe says.

The challenges of black people are challenges globally,” she says. “We have to start with the truth. So often we look at a problem without looking at the truth of the cause of a problem. If the cause of a problem is systematically institutionalized, you can’t solve it without examining the construct of the institution.”

That applies to all aspects of life, she says, not just race. It applies to individuals as well, especially those reluctant to buck the status quo.

“I think that what people who are hesitant can do is learn the truth of one’s self first,” she says. “I can’t do anything to make you feel comfortable if your core is discomfort. You have to do some self-examination sometimes to say, ‘Well, what are my issues?’”

A Home Away from Home

Kwanzaa this year begins Dec. 26 and ends New Year’s Day. The seven days celebrate seven principles: umoja (unity), kujichagulia (self-determination), ujima (collective work and responsibility), ujamaa (cooperative economics), nia (purpose), kuumba (creativity) and imani (faith).

The center puts these principles into practice every day, plus one more: sankofa, which means “it is not taboo to go back and fetch that which you have forgotten.” In other words, people must look to the past to understand the present and work toward a better future.

It’s been just 60 years since those historic African-American firsts at NC State. Three generations don’t erase centuries of oppression and discrimination, Greene says. The official endings of slavery and segregation didn’t automatically wipe out their effects. African-descended people must still overcome stereotypes, perceptions and expectations — unintentional or otherwise — born of those institutions.

John Miller IV, who took over from Thorpe as the center’s program coordinator, says trying to navigate that is exhausting.

“It’s a constant negotiation,” he says. “This hyper awareness of who you are and who your environment dictates you must be and balancing those two.”

Miller, who graduated from NC State with a bachelor’s degree in psychology in 2015 and a master’s in higher education in 2017, frequented the center when he was a student. As well as participating in programming, he often studied and socialized there. The center, he says, was a place he “could bring my entire self.”

The center is one of the places where African-American students can surround themselves with people who share their experiences as people of African descent. Several student resident organizations based in the center, including Peace Church and the Black Graduate Student Organization, provide a sense of community. The staff are there to listen, advise and even offer a hug if needed. Thorpe says the center strives to be a home away from home.

It also strives to help students develop as individuals as well as celebrate their communities. The AYA Ambassadors program hones members’ leadership skills by sending them out to represent the center on campus. Students who need help with problems — racial or otherwise — can talk through their options until they find one with which they are comfortable. There is no one-size-fits-all approach, Miller says. The goal is to help students figure out how to confront intolerance and advocate for equality all while balancing their day-to-day lives. Then they can take what they learn and use it to improve their communities and cities — just as Witherspoon and Clark called for all those years ago.

It’s sankofa in action — planning for the future, connecting with the past. “Walk in your genius, make your ancestors proud,” Greene says.

Thorpe says students who used the center have gone on to become ministers, entrepreneurs, scientists and more, each of them improving their communities, and the world, in their own way. That doesn’t surprise her.

“I’ve always thought the center was such an amazing place,” she says. “I think nothing is impossible here. The things that I’ve seen students do who have walked through these doors, and the brilliance of the minds that have presented here — nothing’s impossible.”

- Categories: