Enduring Legacy

Chester Grant, NC State athletics' first and, for the longest time, only Black employee, inspired generations of student-athletes as an athletic trainer, father figure and friend.

In the summer of 1934, a young Raleigh man was hired for a job with the federal Public Works Administration construction crew that was building the final phase of NC State College’s Riddick Stadium, the school’s on-campus football, baseball and track and field facility.

For a couple of years, he drove a team of mules that cleared the land and shaped the embankment for the west side grandstands for the old stadium, a building that also served as dormitories and the university architect’s office long after the Wolfpack football team left for an improved venue following the 1966 season.

Eventually, the native of the city went to college at North Carolina A&T in Greensboro, then into the United States Army during World War II.

In the fall of 1948, after two years in private business, Chester Arthur Grant returned to NC State to apply for another job, one that paid just a few dozen dollars a week, as the school’s assistant athletics trainer. At that price, he didn’t intend to stay long, but he forged so many strong relationships with young Wolfpack athletes over the years that he didn’t want to leave.

“I was going to stay through one basketball season and then get out,” Grant once said. “When I started, I was only making $25 a week, but they kept giving me a raise, so I stayed on. It’s a decision I have never regretted.

“I enjoy my work and especially the coaches and the boys that I am associated with.”

Grant was NC State athletics’ first and, for the longest time, only Black employee, one who served for 33 years as a father and grandfather figure to generations of football, basketball and baseball players, from Alex Webster to Joe McIntosh, from Dick Dickey to Thurl Bailey, from the Doak brothers to the Plesacs.

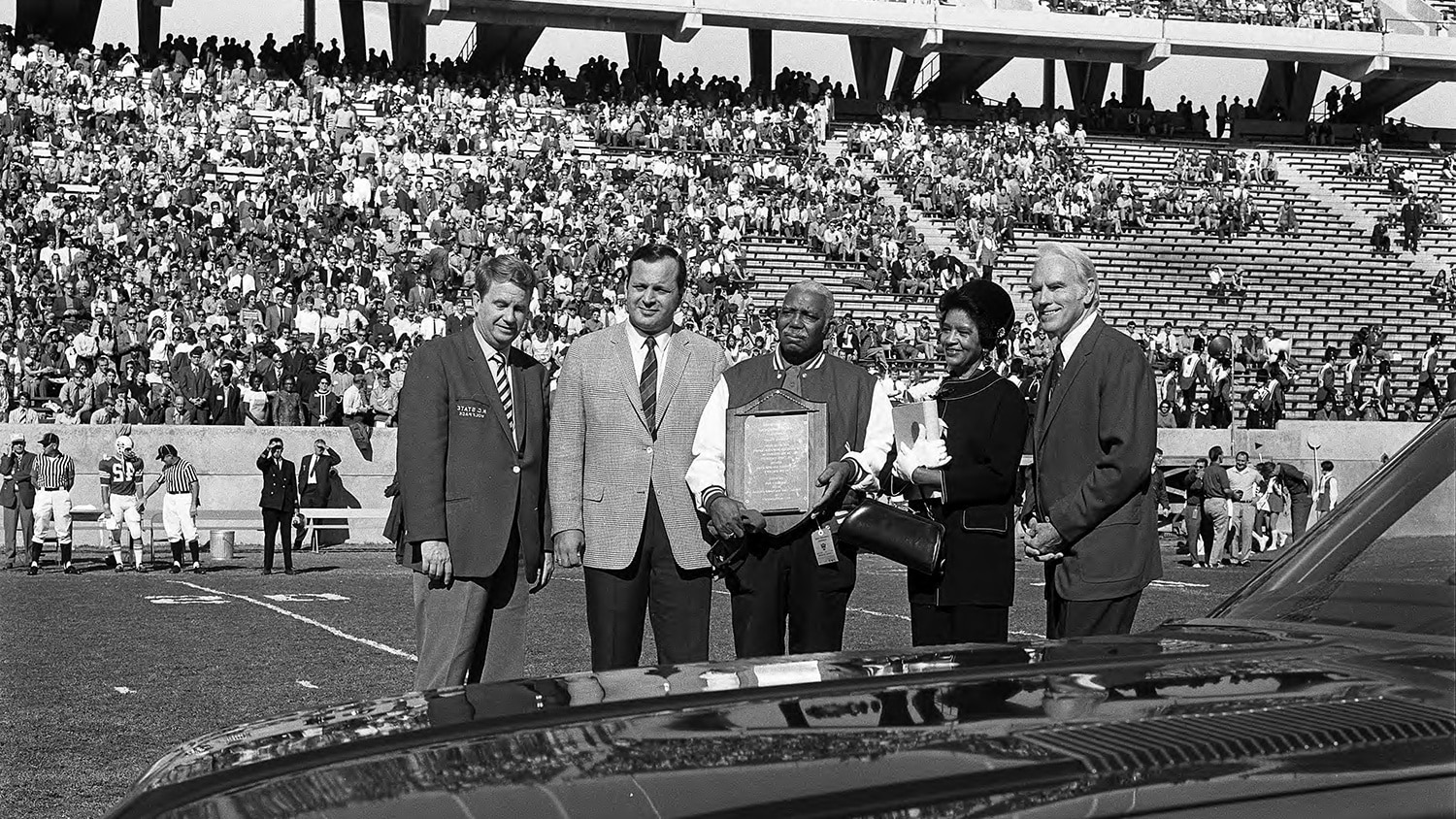

Grant was so beloved by the Wolfpack community that when he reached official retirement age in 1970, a group of donors led by Amedeo’s restaurant owner Dick DeAngelis secretly collected enough money to buy Grant a new car, order several plaques acknowledging his service and throw a celebration at halftime of the Homecoming football game against Virginia at Carter Stadium. The final gift was a book full of congratulatory letters, including one from NASA Apollo 13 commander James Lovell, on behalf of President Richard Nixon. In 1974, the university gave Grant its Distinguished Service Award.

Grant worked another 12 years after that retirement celebration, up until his failing health forced him to finally walk away from his trainer’s tables in the basement of Reynolds Coliseum. In all, he served under four head trainers, seven football coaches, four basketball coaches and two baseball coaches. He died on Sept. 11, 1982, at the age of 76 and is buried in Carolina Biblical Gardens in Garner.

Grant was loved by those he served, especially the players and coaches he would let enter the back door of Reynolds Coliseum during the Dixie Classic and ACC basketball tournament. He was not only an ankle-taping philosopher but also a part-time barber, especially for baseball players who let their hair run afoul of head coach Sam Esposito’s strict grooming rules.

“I knew him a long time,” said the late Frank Weedon of his long-time friend in a 1982 Technician obituary. “He never had any children, but he had a slew here with the athletes. He was a father and grandfather image with the athletes. He treated them in other ways other than just medical. He never had an unkind word for anybody. He loved State. He would listen more than give you treatment.

“He was a good, good person. He knew his business. He knew athletic training. I don’t know of anybody who didn’t have the utmost respect for Chester. It was more than just taping them; he was giving them philosophical and medical treatment.”

After his death, the NC State Athletics Council approved naming the training room in the basement of Reynolds in his honor, one of the first locations on campus named for a Black staff or faculty member, predating the naming of the Witherspoon Student Center (for professor Augustus Witherspoon) or Holmes Hall (for the first Black student to earn an undergraduate degree, Irwin Holmes). The plaque denoting the recognition was restored in 2019 after multiple renovations.

Grant was posthumously inducted into the National Athletics Trainers Association Hall of Fame in 1986, the third African American elected by the organization.

In 2016, former football player Jim Hipps and his wife Kathleen Hipps endowed four scholarships in memory of professors and support personnel who helped them during his pursuit of a degree in biological and agricultural engineering and a graduate certificate in sanitary engineering. One of those is the Chester A. Grant Athletic Trainer Scholarship.

“He was a great individual and he loved helping the kids,” said the late sports information director Ed Seaman at the time of Grant’s death. “He was really a legend around here.”

- Categories: