NC State To Host Screening of ‘36 Seconds: Portrait of a Hate Crime’

The new documentary shares the story and honors the memory of three NC State alumni.

The emotional scars from one of NC State’s most traumatizing moments are necessarily torn off, says director Tarek Albaba in his 99-minute documentary, “36 Seconds: Portrait of a Hate Crime.”

The documentary has been screened in New York, Charlotte, Durham and Cary to sold-out audiences. Monday night’s showing at 400-seat Witherspoon Theatre on NC State’s campus is free for students, faculty, staff and general public who register for tickets.

Albaba, a Charlotte native with 20 years of experience at Hollywood’s largest studios, set out eight years ago to make the definitive film about the murders of three NC State alumni who were shot point-blank at a Chapel Hill apartment complex.

Initially, television and media reports suggested the shootings were over a parking dispute. For years, however, the Triangle’s Muslim community has explored the media bias and courtroom drama to have the shootings recognized as a hate crime against three bright young students whose lives were cruelly snuffed because of religious bigotry.

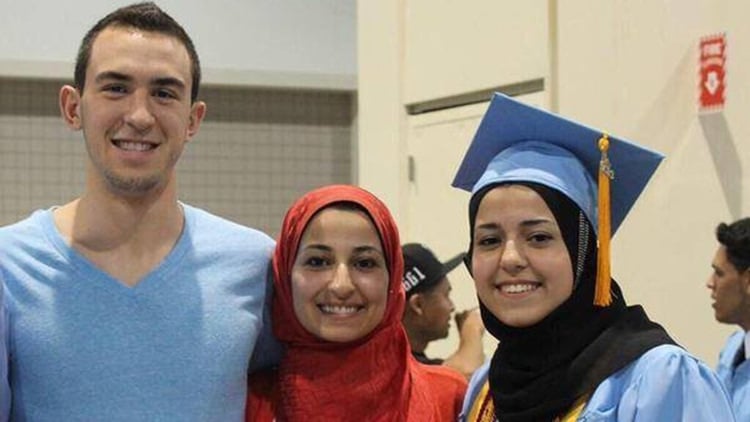

The victims were 23-year-old Deah Barakat, his 21-year-old wife Yusor Abu-Salha, and her 19-year-old sister Razan Abu-Salha, all from the Raleigh area. The married couple were both graduates of NC State, with Barakat enrolled in the UNC School of Dentistry and Yusor planning to enroll in graduate school later that year. Razan was a sophomore enrolled in the NC State College of Design.

Current and recent NC State students may have no recollection of the harrowing events of Feb. 10, 2015, when campuses in Raleigh and Chapel Hill were devastated by the murders. In the initial aftermath international spotlights were on the Triangle, with live remote broadcasts by national networks, vigils from Raleigh to Chapel Hill to Gaza City and calls from President Barack Obama all happening within three days.

The Our Three Winners scholarships were established in the victims’ memories, and the nonprofit Light House Project was founded to serve and empower Muslim communities in the Triangle.

The families were always strong, their calm voices echoing unbearable pain to a global community that began, for a finite time, to listen and learn about the effects of violence.

Justice for the shooter moved slowly. Craig Hicks, a neighbor with a history of hateful encounters with the married students and their families, was convicted of three counts of first-degree murder in summer 2019 and sentenced to three consecutive life terms. The possibility of the death penalty was removed early, and no state or federal hate crimes were charged.

Every hearing, every motion brought the pain back to the fore. The movie does the same — with great intention.

When you attack somebody because of who they, what their beliefs are, what they look like — none of us are safe.

“Yes, the movie is retraumatizing for those who lived through it,” Albaba says. “It’s retraumatizing for the community, it’s traumatizing for the family and it’s traumatizing for the people who know nothing of the story. That’s the point.

“How are you going to create change without people caring? You have to care about these three young lives.”

Albaba has been close to the families, particularly Barakat’s NC State alum brother Farris Barakat, since the one-year anniversary of the shootings. He has worked with them to share even the worst parts of the crime, including the 36 seconds of video taken by Deah Barakat as he was shot, followed by the pleas of the two sisters for their lives and the gunshots that took them.

That footage was shown in the courtroom but never made public until the documentary’s recreation.

“This son of a bitch, Craig Hicks, executed these three kids like they were nothing,” Albaba says. “He left them there to die like animals. They were target practice. [Screw] that.”

The Islamophobia experienced that day, Albaba says, continues in the United States today and in the aftermath of the Oct. 7, 2023, attacks and response on the Israel-Palestinian border.

“When you attack somebody because of who they, what their beliefs are, what they look like — none of us are safe,” says Albaba, who identifies himself and his family as Palestinian American.

Albaba was on campus Monday to film an introduction that will be shown at the screening. He will also be part of a panel discussion that will follow.

“We hope this film illustrates how terrible hate crimes are, with all their ripple effects. They don’t just impact the victim’s families; they impact entire communities and, in this case, millions of people around the world.

“This wasn’t just as simple as a parking dispute. It wasn’t as simple as an altercation between two neighbors.”

In the end, Albaba hopes his retelling of the heinous crime will unify the communities his story speaks to.

“It’s important for you all to be here for one another,” Albaba says in his remarks. “This is where it starts, by sharing their story, understanding what these family members have gone through. That’s how we start to combat hate.

“And we need to do more.”

- Categories: