Battery-Powered Bandages Could Become a Simpler and More Affordable Treatment for Chronic Wounds

Millions of Americans live with chronic wounds, which can take months or more to heal — if they ever do.

Left untreated, chronic wounds can become infected and, in the worst cases, result in loss of life or limb. Unfortunately, many patients are left with little choice but to let their wounds fester and hope for the best. The options currently available are either largely ineffective or prohibitively expensive.

Medical researchers have sought better treatments for some time. Studies show a steady application of weak electric pulses holds promise for certain chronic wounds, such as diabetic foot ulcers — one of the most common chronic wounds in the U.S. and a leading cause of nontraumatic lower-extremity amputations. But today’s best electric wound dressings remain complex, cumbersome and too costly for the average patient.

“A lot of the current options are sophisticated, electronics-based, delicate and not very easy to use,” says Amay Bandodkar, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at NC State University.

With this problem in mind, Bandodkar and a team of experts set out to look for a solution. And they might have found one.

Enlisting partners from Columbia Engineering, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, UNC-Chapel Hill and NC State’s joint biomedical engineering program, Korea University, Georgia Tech, and the Korea Institute of Science and Technology, the team received grants from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and NC State’s Center for Advanced Self-Powered Systems of Integrated Sensors and Technologies (ASSIST).

Thanks to DARPA and ASSIST’s support, the team developed an electric bandage that healed chronic wounds 30% faster than conventional bandages in tests on diabetic mice.

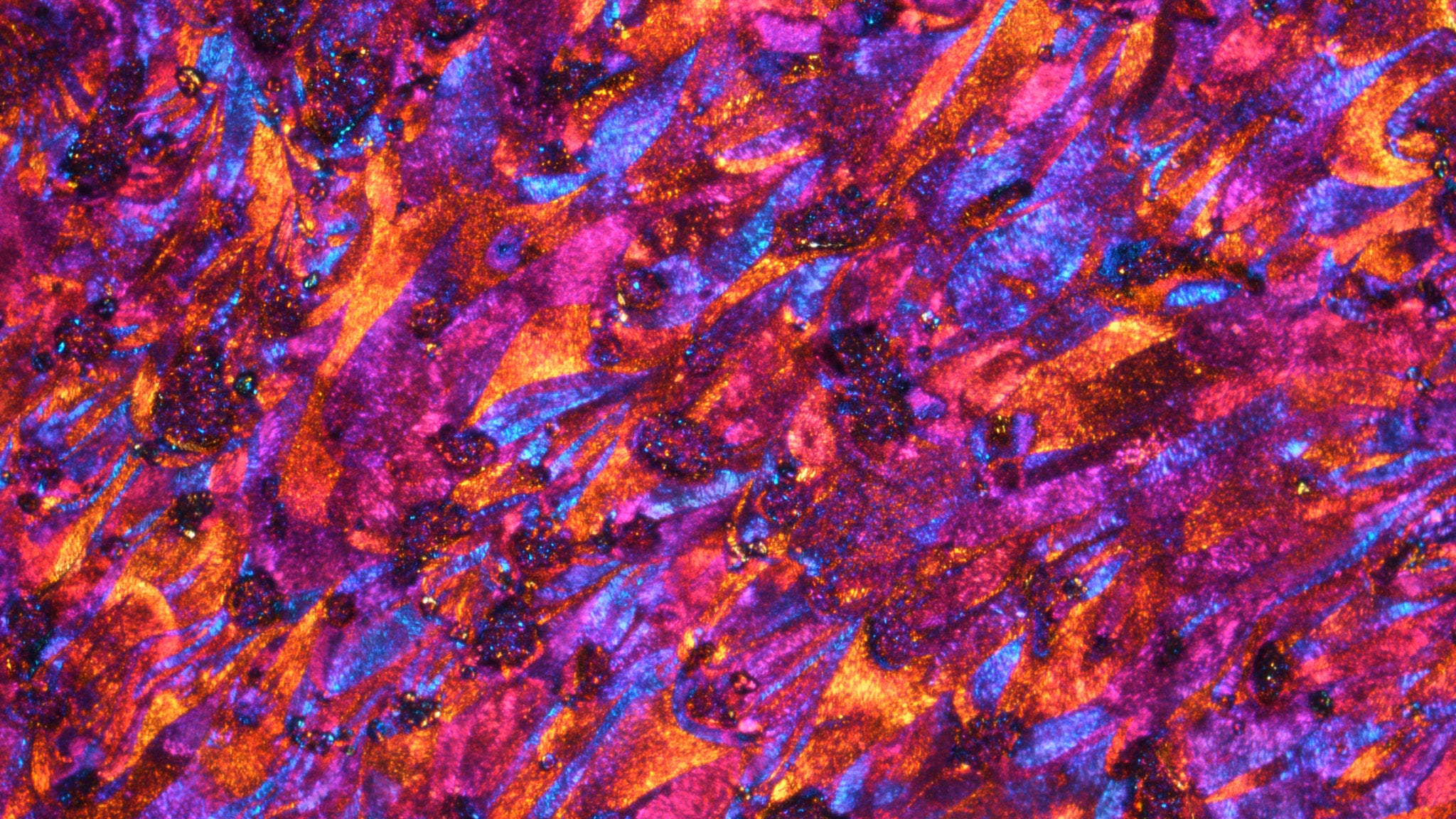

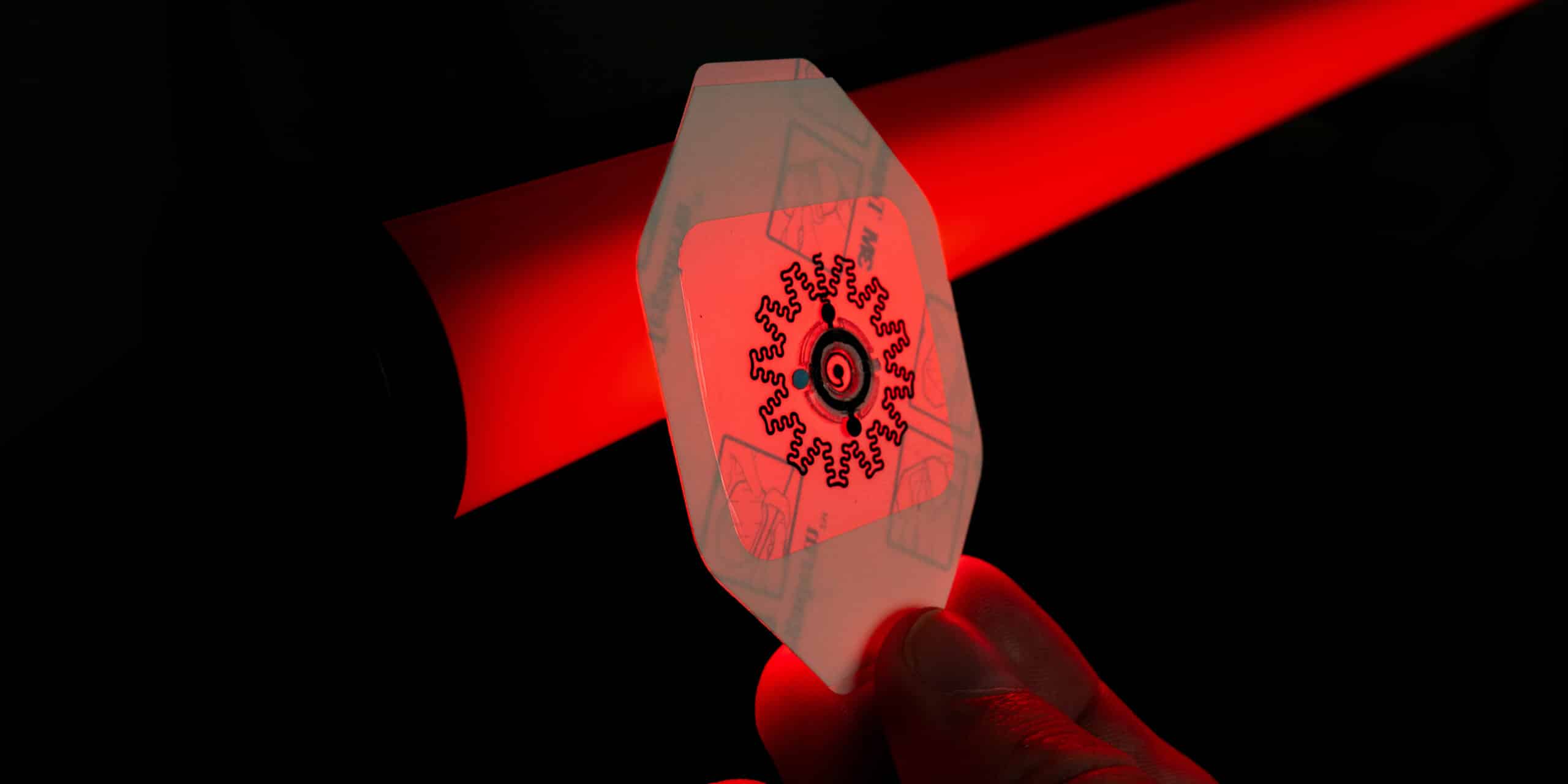

The disposable wound dressings have electrodes on one side and a small, “biocompatible” battery on the other. Simply apply a drop of water to activate it, and the bandage will produce an electric field for several hours.

This fall, NC State’s Office of Research Commercialization filed a patent on Bandodkar’s behalf for the electric bandage technology.

“Anybody, without any training, should be able to use these bandages,” Bandodkar says.

Bandodkar’s research interests have long centered on batteries that are non-toxic and biocompatible. When he realized how many chronic-wound patients would benefit from a better electric bandage, it didn’t take long for the light bulb to go off.

“We were working on battery technology for other applications, and thought ‘OK, there’s a chance we might be able to modulate this for wound care,’” Bandodkar says.

Unlike electric vehicles and certain big electronics — the kinds of applications Bandodkar remains interested in researching innovative new technologies for — an electric bandage doesn’t require much power.

“What’s more relevant is how the electrodes are designed that come in contact with the wound — and what kind of electrical fields these batteries are creating,” Bandodkar says. “Because that’s what drives wound healing.”

Rajaram Kaveti, a postdoctoral researcher at NC State who’s played a key role in the work, says that for the electrical field to be most effective in this application, the electrodes need “to be in contact with the patient at both the periphery and center of the wound itself.”

“And since these wounds can be asymmetrical and deep, you need to have electrodes that can conform to a wide variety of surface features,” Kaveti explains.

To maximize the chances that — should they eventually receive FDA approval — the electric bandages can be made affordable for all patients, including those on Medicare or Medicaid, Banddokar says they’ve been careful to design the bandages to be compatible with existing manufacturing equipment.

Bandodkar says the bandages can be manufactured using the same roll-to-roll printing and die-cutting processes as traditional wound dressings.

“So it should be fairly easy to translate it from the lab to the market,” Bandodkar says. And he estimates the overhead costs could be as low as “a couple of dollars per dressing.”

Bandodkar is the co-corresponding author of a paper on this work, “Water-powered, electronics-free dressings that electrically stimulate wounds for rapid wound closure,” published in Science Advances.

For more information, including how to inquire about potentially licensing this technology, contact Assistant Director of Licensing Bradley Aycock at braycock@ncsu.edu.