Podcast: Preserving Parasites

Skylar Hopkins, an assistant professor of applied ecology at NC State, explains why some parasites need protecting. Read on for highlights.

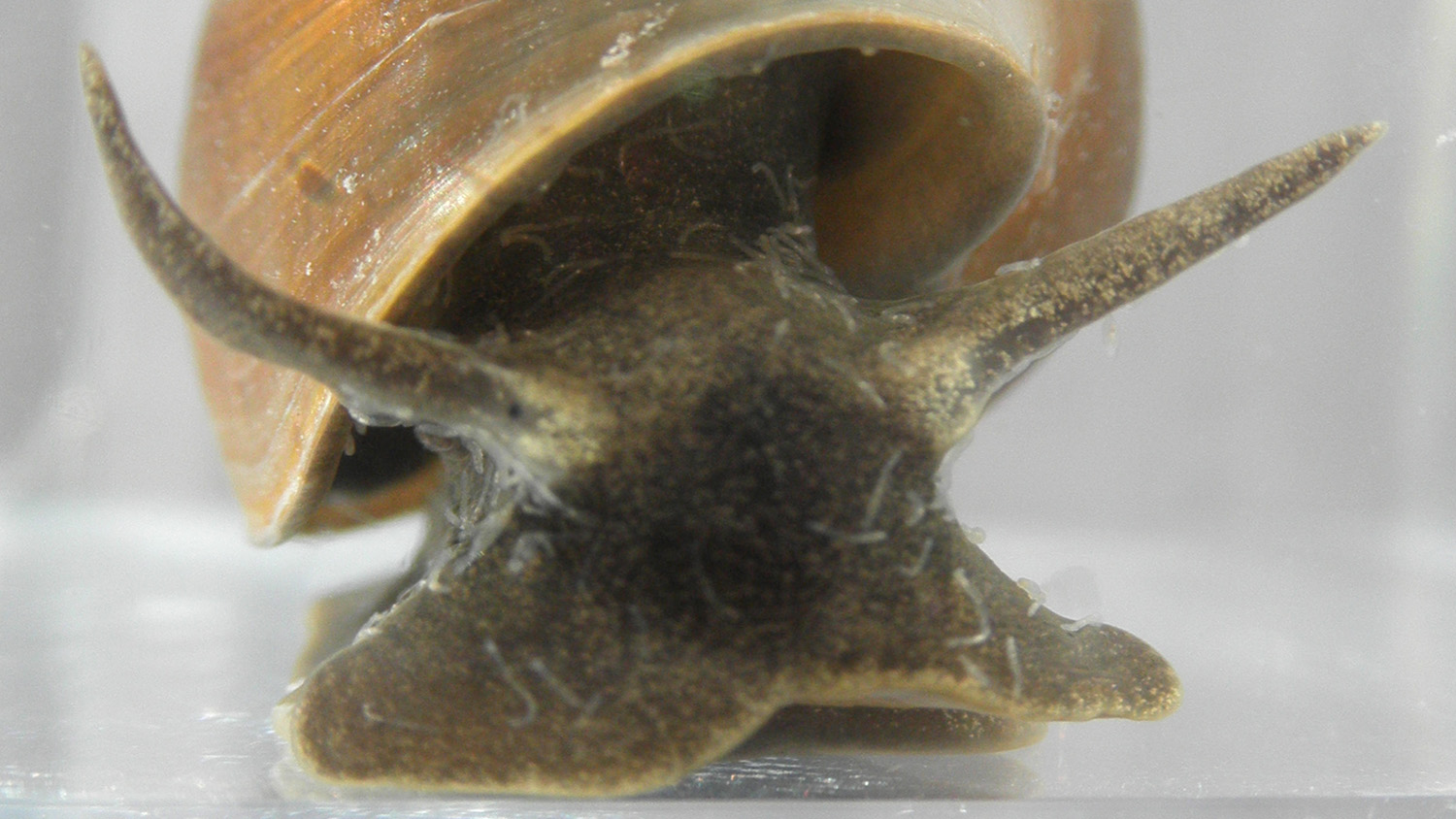

“Parasite is a term that we apply to really any organism that lives on or in another organism, and it gets its resources from that single host organism,” Hopkins says. “And so by that definition, there are actually 15 different animal phyla that contain parasites. That’s everything from lice to mites to intestinal worms to parasitoid wasps. A tiny fraction of all of those species impact people or our domesticated species, and another tiny fraction cause wildlife population declines. And we’re not advocating for conserving any of those harmful parasite species.

Parasites actually save us a lot of money every year. For example, we know that parasitoid wasps can infect and kill crop pests like caterpillars, and that saves us billions of dollars per year in the agricultural sector that we’d otherwise need to spend on pesticides.

“We also know that parasites are really deeply connected in food webs, such that they really play important roles in energy flow within ecosystems. We’re not exactly sure what would happen if we lost a big chunk of the parasite biodiversity from ecosystems, but we do know that food webs would change a lot and we’re not really sure what consequences that would have.”

Hopkins and other researchers think that 10% of all parasite species could go extinct by 2070, due to ‘primary drivers’ of extinction such as changes to habitat or coextinction, where the host animal goes extinct, taking the parasite with it.

We know that the (extinct) moa had parasite species that we don’t know from any birds that currently exist in New Zealand today. And that suggests those parasites went coextinct with the moa. Or as I like to put it, moa extinctions cause even moa parasite extinctions.

Hopkins and her colleagues have a 12-step plan for preserving parasites from extinction. “Now, sometimes we do need to remove parasites that are endangering their host species, but in case of the California condor louse, and probably other endangered species, the parasites aren’t really harming their hosts,” Hopkins says. “And so we should at least have protocols that allow us to think about parasite conservation. Or at least if we’re going to drive the parasite extinct, that we do it on purpose, not accidentally.”