Wes Is More

Though his ninth season at NC State ended Monday night in a heartbreaking loss to Connecticut in the NCAA East Region final, NC State women’s basketball coach Wes Moore has established a tradition of success that mirrors legendary women’s basketball pioneer Kay Yow.

You’ve seen him on the national stage, where his down-home humor, sleeve-worn emotions and discount haircut are staples on the sidelines for the NC State women’s basketball team.

Over the last nine years, you’ve seen him rebuild the Pack into a nationally powerful program that has earned three consecutive Atlantic Coast Conference tournament championships, the school’s first regular-season title in 32 years and four consecutive trips to the NCAA Sweet Sixteen.

You’ve seen him embrace his players as they walked off the court, both in confetti-decorated celebrations and disappointment in a rare defeat.

Does anybody here really know Wolfpack women’s coach Wes Moore, who once described his only talent as “I’m a really good eater”?

A native of Dallas, Texas, he’s a former office supply salesman who used that job to pay his way through college, working a year at a time to save money so he could go to school the following year, alternating between being a Dwight Schrute in boots and a Texas Pete Maravich.

Frank Weston Moore was a late bloomer whose educational journey took him from his hometown Dallas (Texas) Christian College to Johnson Bible College in Knoxville, Tennessee, thanks to strong childhood friendships, the Baptist-based Royal Ambassadors’ youth program and a boost from his first college coach, Gene Phillips, a former ABA player and NBA draft pick.

For the longest time, he was a scrawny little guy who hid his eating talents pretty well, even after marrying into a family with four generations of eastern North Carolina-style barbecue restaurant experience. He was basketball- and baseball-crazy, working off his calories in driveway pickup games and daylong sandlot games.

He was a scrappy point guard who eventually earned a degree in religious studies from the private Christian school.

Moore, last year’s national coach of the year winner and a finalist for the same award again this year, has matched and in some ways exceeded the accomplishments of legendary Wolfpack head coach Kay Yow, the Naismith Memorial Hall of Fame inductee who once hired Moore to be on her staff (1993-95).

That was long after he spent six months as a prison guard at a Jamesville, North Carolina, correctional facility, when he and his wife were still newlyweds living in her hometown. He escaped when a job opened up at a local office supply store, the same kind of job he had in his hometown to pay his way through college.

When he had saved enough money, he and Linda moved back to Knoxville so he could finish his first degree at Johnson (1984), then enroll at Tennessee to earn a bachelor’s degree (1986) and a master’s degree (1987) in physical education. While there, he spent his off-time and summers working camps for Volunteer women’s coach Pat Summitt, another pioneering women’s coach known for her dark stares and multiple national championships.

Shortly after he earned his master’s, Moore took his first coaching job at NCAA Division III Maryville College, a 25-minute drive from Tennessee’s campus, where he coached both women’s basketball and softball.

“When I graduated from college my choices were to coach a boys’ high school team and teach biology six times a day,” Moore said after he was first hired at NC State in 2013. “Or I could go to Maryville College and coach a women’s team that was 1-25 the year before.

“But the key was I didn’t have to do any teaching. I would have been studying more than the kids if I had to teach any classes. So I went to Maryville.”

And that’s how he began a march towards nearly 800 career victories, 13 conference coach-of-the-year awards and the 2021 Women’s Basketball Coaches Association National Coach of the Year Award, which is named after Summitt.

Frugal Beginnings

When Moore was still an infant, his parents and two sisters moved from Dallas to Houston. A year later, his mom and sisters moved back to their hometown and his dad drifted away. Moore met him only once after that while still enrolled at Johnson College.

Throughout his youth, Moore was always scrapping, both for financial stability as his mother worked three different jobs, and in athletics. He was always looking to save money. He was frugal in ways that only children of the 1970s recession or grandchildren of the 1930s Depression can fully understand.

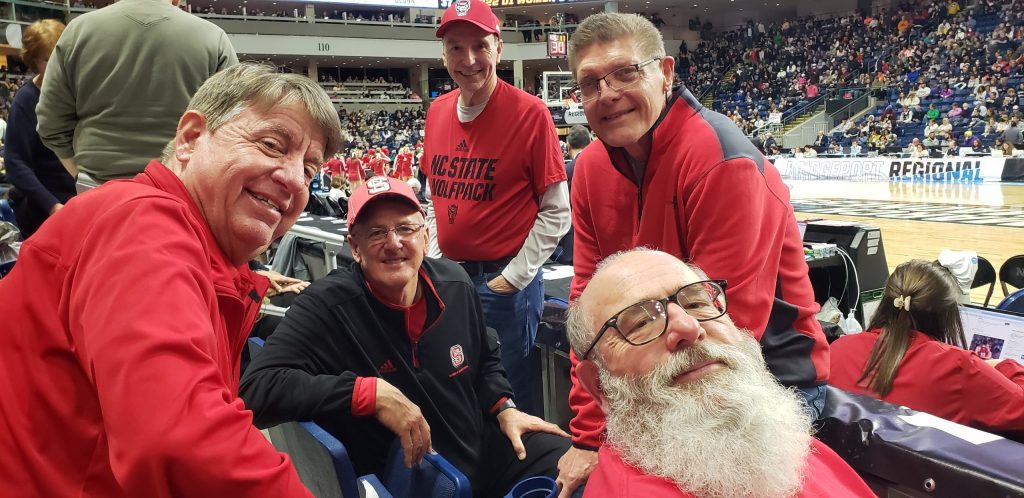

But his quest to save money never begat disloyalty, say his four closest friends, all of whom have traveled with the Wolfpack to the NCAA’s Sweet Sixteen the last four years to see their buddy coach in college basketball’s biggest event: Gary Jones, Larry Carruth, Grant Allen and Mark Nevels.

“Wes grew up with a single mom and she worked all the time to provide for her family,” Allen says. “He really raised himself. He learned how to scrap at an early age, just to get by and to accomplish things. We talk about him working the system in a fun way, but we were always impressed that he was able to get where he wanted.”

Still, even as he avoided every toll road in Texas, Moore liked a little bit of flash.

“He had this 1963 Impala that probably cost him $200,” Nevels says. “With $1,000 chrome wheels.”

Going to Texas Rangers baseball games, the gregarious youngster could always talk a suited businessman out of an unused extra reserved ticket, sell it to buy two box seats and then sell those to buy just enough general admission passes to get him and all his friends into the game.

Nothing meant more than the tickets Moore got them to this past weekend’s games in Bridgeport, Connecticut, to see State win in dramatic fashion over Notre Dame on Saturday, followed by its heartbreaking loss Monday night in double-overtime to women’s basketball powerhouse Connecticut.

They were the guys who slipped into those baseball games with Moore and into nearly as many Dallas Cowboy football games. They were the ones who helped keep him out of trouble with driveway pickup games and sandlot baseball games.

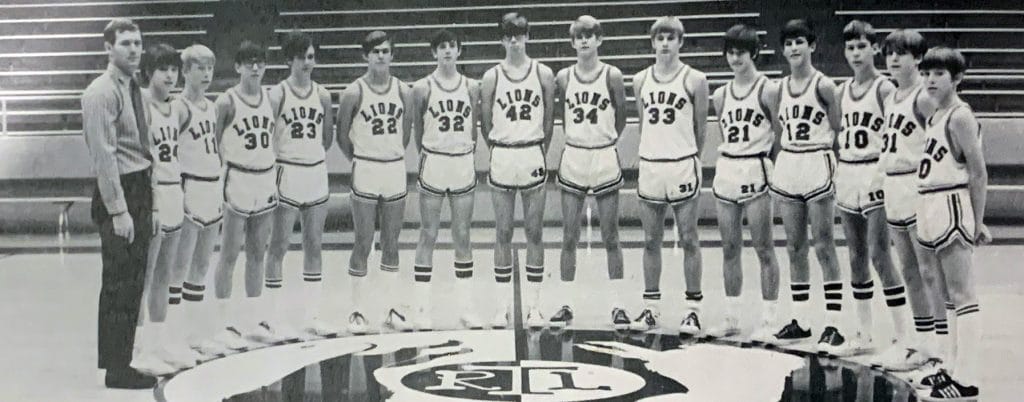

They were the kind of friends Moore enjoys to this day spending time with, even if they did bring a junior high yearbook to show the current members of the Wolfpack basketball team pictures of Moore as a 13-year-old guard wearing jersey No. 13. The players might have had to squint to recognize their coach, but the open car-door ears gave him away.

These are the guys Moore always depended on, through their days at First Baptist Church of Carrollton, Royal Ambassador summer camps and high school basketball games. They are the guys he makes sure to call when he swings through Texas to join him at Marshall’s Bar-B-Q or the Tupinamba Tex-Mex Café.

“It’s really easy to lose touch with someone from 40 or 50 years ago,” Jones says. “Wes has never let that happen. He’s the one who has been intentional about staying in touch with us. He calls us when he comes to town.

“He’s the one who gets us all together.”

Only one thing has changed about the ever-reliable coach and friend: “In the last couple of years, as his teams have gotten better, he’s picked up the check for some of those meals,” says Jones, laughing.

He Tells a Good Joke

Moore has a quick wit that travels the gamut of good storytelling to spontaneous one-liners. When caravanning around the state with football coach Dave Doeren and men’s coach Kevin Keatts before COVID cancelled that annual tour sponsored by the Wolfpack Club, he often stole the show with his array of dad jokes and rubber-chicken banquet groaners.

He can tell a joke and make it believable enough for a follow-up question.

“I remember this one time we were playing a game and I sent six players out on the court,” he told reporters following this year’s Louisville game. “The ref looked at me and said, ‘Coach, you have too many players on the court.’

“That’s my lineup,” Moore said.

“But coach, you have six players on the court.”

“That’s my lineup.”

So the official called a technical foul.

Moore says he whipped around to the parents in the stands and said, “See, I told you I could only play five at a time.”

It’s a standard coaching anecdote, told well by Moore. A reporter raised his hand and asked, “What year and where was that game, coach?”

Moore had the same mischievous and disbelieving look late Wolfpack men’s coach Jim Valvano used to have when someone asked for more details about one of his outlandish stories, like the time he said one of his players was waiting to hear if his pregnant sister had delivered a boy or a girl “so he could find out if he was an aunt or an uncle.”

Saturday afternoon, Moore relished a victory over ACC-foe Notre Dame, in which Wolfpack graduate student Raina Perez stole the ball at midcourt and drove in for a go-ahead layup in the first Sweet Sixteen win of Moore’s career and the first for the Wolfpack since 1998. “You know that show ‘Everybody Loves Raymond’?” he asked reporters. “Now it’s ‘Everybody Loves Raina.’”

His players just appreciate his phrasing. “He’s always telling us not to play ‘dead-squirrel defense,’” says sophomore guard Diamond Johnson. “He says, ‘You’re just sitting there like a dead squirrel in the road. Don’t be a dead squirrel.’

“I just love that.”

The jokes often mask his on-court intensity and the basketball brilliance he has acquired over 30 years of coaching, especially when times get a little rough.

At the ACC tournament in Greensboro earlier this month, Moore said about midway through the season his ultra-veteran team grew tired of it all and they came to an uneasy truce of tolerance. By the time the regular season ended, they had all made up and were listening to each other again.

“I still think they are tired of looking at my face,” Moore said.

Change Comes Hard

Every Tuesday for lunch, Moore goes to the same Cary barbecue restaurant because it has a $2 rib bone special. It’s the Midwestern style of ribs, nothing like the brisket he grew up on in Texas or the vinegar-based pulled pork his wife’s family made down in Jamesville.

Still, he loves them—mainly because the price is right.

The only problem? The restaurant has little plastic packets of artificial juice for his unsweetened iced tea. So he takes his own lemon slices.

Moore is frugal but demanding.

So it’s hard to believe that Moore and some former assistants are coming up on their 20th consecutive year of going to Las Vegas, America’s most in-your-pocket city. They play cheap golf, find rooms that give gamblers steep discounts and stay away from the craps tables.

Moore always knows how to find a bargain.

A Faithful Couple

They weren’t supposed to meet, you know. Linda Hardison of Jamesville, North Carolina, was going to go to nursing school at East Carolina or enroll in a similar program at the local community college. Then she attended a summer camp of the Johnson Bible College’s traveling choir in Washington, North Carolina, and was convinced by her new minister to spend a year at the Knoxville, Tennessee, private school.

By chance, she met a basketball player named Wes Moore, someone she was not interested in really getting to know because of a back-home boyfriend. They were drawn together, however, by the power that makes the unlikely possible.

He wooed her with convenience store doughnuts and quiet dates at a highway overlook where they watched the rushing waters of the French Broad, Tennessee and Holston rivers churn together.

They knew after only a few dates that they would marry, but their wedding was delayed. Linda had won the title of Miss Martin County and couldn’t really have a social life until after she competed in the statewide pageant. The day after the competition ended at the downtown Raleigh convention center, Moore took her to the Angus Barn and proposed.

“How ironic is that, getting engaged here in Raleigh?” Linda Moore says.

They’ve journeyed together for 42 years. She served as an admissions counselor at Johnson College because, as married staff members, they could live for free in campus housing. At the time, an assistant coach for the men’s team at Maryville was Houston Francher, who made multiple stops in men’s college basketball, but is now a member of Moore’s staff at NC State.

After leaving Maryville for an assistant job at NC State from 1993-95, Moore coached three years at Francis Marion in Florence, South Carolina, 15 years at Chattanooga in Tennessee and now nine years in Raleigh.

What Linda Moore finds most pleasing at this stage in their lives—Wes Moore turns 65 in April — is that he has finally found ways to relax after all those years of building, working and scraping by, either by searching for Dallas Cowboys or Texas Rangers items for his COVID isolation-inspired memorabilia room or just by staring out the windows of their Holly Springs home.

There’s something, she says, the coach finds fascinating and satisfying about watching the birds, the (live) squirrels and the deer that show up at dawn and dusk looking for a free meal in his backyard.

A Chance Encounter

They weren’t supposed to meet, you know. Moore was coaching at Maryville, but he was starting to look for other opportunities. He had gotten some interest from Division II Catawba in Salisbury, so one summer he began watching some recruits that he thought might be good for that school, not just ones who might be available for Maryville.

Sitting at a gym one afternoon during an Amateur Athletic Union tournament in Knoxville, Moore bumped into legendary NC State coach Kay Yow.

“Wes, what are you doing here?” she asked.

He told her why he was watching players from North Carolina and they began to talk. They talked basketball and religious philosophy through the games and most of dinner. They talked about how to build a program and how to deal with players.

“Wes, I have an opening on my staff, why don’t you come interview for it before you think about another school,” Yow told him.

Moore was scheduled to leave for vacation, but rerouted himself through Raleigh so he could meet Yow’s staff and then to New York to meet NC State women’s athletics administrator Nora Lynn Finch, who was attending meetings in the Big Apple.

Before he knew it, he had his first offer at NC State.

“What Kay saw in Wes when she first talked to him, and it was really evident in their conversation, was that he related to post players,” Finch says. “She saw that he was a really good teacher.

“Most coaches are not great teachers, but Wes was and still is. Kay picked up on that early.”

Moore only spent two seasons in Raleigh his first time, recruiting some of the players that helped Yow reach the 1998 NCAA Final Four in Kansas City, the only time in her career that she advanced to college basketball’s biggest weekend.

By then, Moore had gone to Francis Marion to become the 1997 Peach Belt Conference Coach of the Year and to take his own team to the 1998 NCAA Division II Final Four.

Soon after, Division I Chattanooga came calling and Moore spent 15 years coaching the Mocs to unparalleled success in the Southern Conference, with a school-record 358 wins during his tenure. He won 12 SoCon regular-season titles, nine league tournament titles and once had a 27-game winning streak that included a victory over Rutgers.

When Yow died in 2009, Moore was a finalist to be named her replacement. Instead, former Tennessee point guard Kellie Harper was hired to lead the program. Both Harper and her husband Jon were once assistants for Moore at Chattanooga and Jon is still a regular golfing partner.

Soon afterward, Moore was named head coach at East Carolina, a position he held for only three days before deciding to stay at Chattanooga. He was there another three years.

In 2013, new NC State athletics director Debbie Yow decided to change coaches in the program her older sister operated for 34 years. Moore was her first interview.

“We had dinner at a restaurant in Cary the first night of his visit here,” Debbie Yow says. “We were supposed to go to campus the next day to meet the players, the staff and the faculty athletics representative.

“After dinner Wes just piped up and said, ‘So, are you going to hire me? We weren’t even close to finishing the interview.”

Yow, a veteran administrator at multiple schools, had never been asked such an audacious question by a coaching candidate. Before long, Moore was named the fourth full-time coach in NC State women’s basketball history.

“That’s just who he is,” says the retired athletics director. “It’s a trait I found attractive. He was not being coy. There was no game-playing. He really wanted the job.”

Yow explained that she didn’t have a lot of money for a long or lucrative contract. She explained that Reynolds Coliseum was due for a much-needed update , not knowing that when it happened women’s basketball and other programs that shared the historic arena would have to be displaced for nearly two seasons. She explained that he might need to scrap and make do for a while.

That was all in Moore’s wheelhouse.

“I told him what we had to offer financially and that it wasn’t as much as we wanted,” Yow says. “But I also told him that we would build it together and that if he did well, he would be taken care of.”

Moore was initially paid $385,000 when he was hired in 2013 and earned a raise to $460,000 in 2015. In 2019, the year before he won the first of three consecutive ACC titles, Moore signed a six-year contract extension that guarantees his contract at $750,000 annually through 2025, earning more than $250,000 in achievement bonuses for his successes this season and a $75,000 pay raise for 2023.

He still takes his own lemon wedges to lunch.

- Categories: